“Please, Dr. Malan, please listen to me for a moment. I am sorry I lost my temper and manhandled your assistant, but this matter really is important. I would never have ventured to take up your valuable time if Mr. Warde had not assured me that you were the only person who could help.”

“I see. The only person who could help.” She still frowned, but there was a happier expression on her face. “Very well, what is it you want from me?”

“I want to know what this is, Doctor.” Kirk reached in his pocket and handed her the drawing. “Mr. Warde told me it was the symbol of a cult that once existed off the East African coast. I wonder if you can tell me any more?”

“Let me see it.” She took it from him and held it under the light. Almost at once her face changed. The frown and all expression went out like a lamp switched off and her eyes grew wide and staring. She swayed for a moment and leaned against the desk.

“L’Albert,” she said slowly. “Le petit Albert. Where did you get this, Mr. Kirk? This thing is death. It is ‘Maksur Walad’—‘The Broken Child’—‘The Very Holy Thing’!”

Kirk watched her before replying and as he looked, he knew that to her the thing she was holding was fear. It was fear with two faces like a playing card and they were both watching her. It was the Negro witch-doctor and the white devil; all they had done, the forest rites, the drums, the slave ships and the tortures were looking at her from that rough scrap of paper.

“I found the original of this in the room of a friend of mine who died. I may be wrong but I have a feeling, just a feeling that this image might have had something to do with the death of my friend.”

She nodded, but she didn’t answer him at once. She crossed to the basin and filled a glass of water, then she took a bottle of small green tablets from the shelf, swallowed one and drank. When she turned, he saw that the fear had gone from her eyes and she was once more quite normal and very European and civilized.

“I am sorry, Mr. Kirk. I shouldn’t have spoken like that, but seeing that picture upset me. It is nothing really, just a primitive superstition that was once brought to my people from yours.”

“From my people, Doctor. Then this thing is European?”

“Oh, yes, it’s origin is purely European. It started during your Dark Ages”—there was a slight accentuation of the adjective—“as a simple cult of the Devil. There were two forms which were known as ‘Albert le Grand’ and ‘Albert le Petit.’ It is the second one that concerns us. It is all well documented and you can read about it in Montague Summers.” She broke off for a moment and lit a cigarette. She inhaled deeply and sat down on the edge of the cot.

“At the beginning this cult was identical to a hundred others. It was the usual kind of thing; a looking-back to the old gods, Pan, Hecate, Set-Osiris and merging them as an anti-Christian symbol. There was nothing important about it and it should have died.”

“But it didn’t die, did it, Doctor?” Under her manner, Kirk could still see a little of the frightened child looking out at him.

“But it didn’t die, it survived. It hung on in one small area in France till the Revolution began. Then it changed its form and it began to grow.

“You will remember that during the ‘Terror’ many Frenchmen fled abroad. Some of them came here, some went to other parts of Europe and a great number went even farther afield to the French colonies, including Mauritius. On at least one emigree ship Petit Albert went too and I’m afraid that among my people he found very fruitful ground.”

“You mean that it became some kind of Voodoo cult?” As he listened to her, Kirk’s theory began to weaken. This was not what he had expected or wanted to hear. Nothing like this had killed a girl disguised as Gerda Raine. No woolly heads bowing before the fire as they offered cocks to Papa-Loy had taken her to the river. He was on the point of believing that he was wrong from the start when she went on.

“Yes, in one form you might call it that, I suppose. In Mauritius and the Seychelles it was similar to Voodooism; just childish nonsense and a source of annoyance and embarrassment to the missionaries. Nothing more. When it reached Madagascar however, it was to become quite different.

“Tell me, Mr. Kirk. Have you ever heard of a person called Ranavalo the Cruel?”

“Ranavalo? Let me think.” Kirk frowned and for a moment his hand drummed quietly on the wall behind him.

“Yes, I think so. She was one of the queens of Madagascar wasn’t she? About the middle of the last century.”

“She was the queen, the great queen; the greatest of a line of female rulers and she held Madagascar for over thirty years. During those years it is possible that she killed more than Attila and Tamerlaine put together.” As she spoke, Kirk knew that to the educated, westernized Dr. Malan, Ranavalo was not just a name from history but a thing of terror.

“If you are to understand what I am trying to tell you, Mr. Kirk, you must try and picture this woman. She was educated, yet she worshipped idols. She was always dressed in the height of Paris fashion, yet she lived in seclusion; too holy to be approached by her people. She relied on European advisors, but she ruled by threat of torture and her avowed aim was the destruction of all manhood except in the Hova tribe. At the same time, this woman was a doting and loving mother to her only son.”

“I see,” Kirk’s hand stopped drumming on the wall and he stood quite still, staring at her. Like pieces of a puzzle the facts were fitting together. The queen who worshipped idols, the brightly dressed woman who lived alone, the destroyer of all virility and the good mother.

“Go on, Doctor,” he said. “What was the connection between Ranavalo and ‘Petit Albert’?”

“There was a man called Jean Laborde. He was an engineer and he was shipwrecked on the Madagascar coast. He became the slave of the queen and later the greatest man on the island. He built her arsenals and foundries for guns. Through him she was able to equip an army capable of driving back a combined force of French and English. I think that he may have done something else to her. It was about the time of Laborde’s arrival that she first heard of Petit Albert.”

“I see, and she changed it to her own ends?”

“Oh, yes, she changed it. It ceased to be a popular devil cult and took on a more private role reserved to the queen and her intimates. She put away her own idols; snakes and precious stones and became herself a deity. The all-powerful mother figure, with this her symbol.” She took the paper from the desk and handed it back to him.

“Thank you.” Kirk took the paper and glanced at it. Everything was clear now. This was the broken boy, the man who could never escape because its limbs hinged backward, the talisman of decay.

“And I suppose the son became part of the cult?”

“Oh, yes, he was part of the symbol. He had once been a Christian, it seems, but because she loved him, she left him in peace. Once the new religion had started however, she changed. He pleaded for the lives of certain prisoners who were to be killed and she put him away. She loved him very much and he was kindly treated on the whole. He was put away in a nicely furnished room below the ground and left there. From time to time they lowered food and water to him. I understand that he lived to be quite an old man.”

“Thank you, Doctor, thank you very much indeed.” Kirk smiled at her for he was almost home. In his own mind there was no doubt left. It could have been that way and if it was there was no problem as to why Gerda Raine’s substitute had died.

A cult of women, he thought. Strong women with weak sons, whom they dominate; women whose husbands have left them perhaps for someone younger and fresher; women with one thought left, the protection of the sons who they dread may leave them. As he thought of this, he could almost see the faces of Mrs. Carlton, Mrs. Brett and Mrs. Travers looking at him and he heard their words. “My husband—died.” “He was a medical missionary and he travelled a great deal. He did nothing remarkable, he just—died.” “You came here, Mr. Rouse, just after my husband—died.”

But the husbands had not died, they had gone away. Mr. Carlton hadn’t died; he had changed his name to Rouse and after his fling had become the lodger of the formidable Mrs. Travers. And if she had been a friend of his wife the circle was complete.

Just given the possibility of that and he had the truth. Given a number of women like that and everything was clear; always supposing that they heard the story of Ranavalo the Cruel. And why couldn’t they have heard it? One woman he had seen had been the wife of a medical missionary and in her house had been the carving. Suppose that she had come back after her husband’s end with the knowledge and also the bitterness. Suppose that, quite by chance, that woman had seen the house with the carved inscription on the lintel and revived the cult in England. And then what? What would have made it once more a killer?

Perhaps a little go-getting girl like Gerda Raine who had threatened to take away one of those weak, well-loved sons. He needed just one more piece of information to make suspicion a certainty.

“Thank you, Doctor. Just two more questions and I will leave you in peace. Did this cult continue after the death of Ranavalo or did it end with her? If it has survived, do you imagine it ever spread to Europeans?”

“I don’t know,” she said and her voice was far away and distant. “It carried on for a time under the three queens that followed her, but in a milder form. Since then—who knows? Remember, it started in medieval France and crossed half the world before Jean Laborde took it to Madagascar. Now it is just a folk tale to frighten children, but who can tell. To me it seems unlikely that anything so tenacious of life would die easily.

“Now, Mr. Kirk, I have told you what I know about this business, so tell me something. Just what is your interest in Petit Albert?”

“Sorry, Doctor. I’m most grateful for your help, but I can’t tell you at the moment. My hands are tied. One day, perhaps, I will be free to tell you and if so I will come back and let you know. Till then, goodbye, and thank you.” He smiled at her, bowed and walked out of the door.

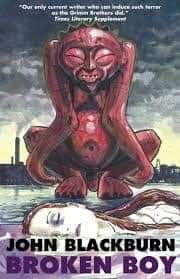

Broken Boy (1959) by John Blackburn