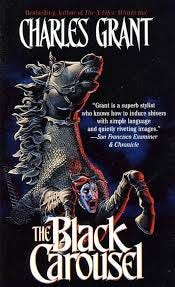

Readers unfamiliar with The Black Carousel (1995) may prefer to read these notes only after reading the collection.

In The Black Carousel (1995) Prologue, the movers and shakers of Oxrun Station welcome their new chief of police, Deric Stockton. Deric is former chief Abe's younger brother; it's a tradition in the Station for Stocktons to run the cops. Deric meets our narrator, who is reluctantly ready to bring the chief up to speed on their little town and its soured shadows.

"Penny Tunes for a Gold Lion” demonstrates a basic rule to be followed by single, middle age, underachieving postal workers like Casey: Don't ride the carousel lion at the carnival that visits your town. Casey "holds on," with a tight grip, to his home and garden, but a midway temptress might be the poison for everything he appreciates. Or: the poison already within his dissatisfied soul is finally strong enough to act for itself.

"Will You Be Mine?" begins on the worst day of twelve year old Fran Lumbaird's life: her parents have dragged her from her city life to the semi-rural no-horizon of Oxrun Station.

When the breeze blew and things shifted just beyond the range of clear vision, she felt like she was trapped in one of those crazy dreams she got whenever she had a fever. A dream where things had sharp edges, even the pillows, yet nothing ever cut her and she never quite bled and nothing was ever quite in focus. A dream like looking through glitter-laced gauze, where every footstep was a gunshot and every whisper a shout and every color hurt her eyes but didn’t make her turn away. Nothing ever made sense in a fever dream — she could fly, she could die, she could carry a tune — and nothing made sense now.

The story then follows Fran for several weeks as she interacts with fellow future sixth graders. Together they visit:

"Pilgrim’s Travelers are here.” [Kirt "Kitt" Weatherall] gestured vaguely. “On the otherside of the Road.”

“Travelers? What’s that.”

“It’s a carnival thing, like a circus kind of.You know, rides and food and stuff. Sometimes they stay just for a little while, sometimes it’s like they’re around for practically the whole summer.”

“Oh.” No excitement, no anticipation. She could just imagine what a circus would be like in a dump like this, especially one that had no place else to go.

"Will You Be Mine?" ends as a friend -- to be shared with no one else -- is bestowed on Fran. By the time we reach this point, the epiphany and its implications provide no pleasure.

Is Grant allegorizing puberty and its eccentric adolescent rites? He strikes a libidinal note early, a moment of insight as Fran talks with her father.

The air was still. Warmer. Insects whispered in the shrubs and trees. The smoke from his cigarette hung too long before drifting away.

She didn’t make room when he straddled the railing; his right knee touched her left elbow, and felt hot. She didn’t look at him, but she could smell him. The Daddy smell — cigarette smoke and hot jeans and sweat and something else that made him only him, no one else. In the dark she knew it was him; from a zillion miles away in a strong wind she knew. Most of the time it was a comforting thing; today it was annoying....

Fran's resentment over relocation also slows her ability to navigate the unwritten rules governing her new clique. She senses something strange about a couple of new acquaintances, but Oxrun's real sinister weirdness is occluded.

Nineteen year old Drake Saxton takes a ride on the Pilgrim Travelers' carousel in "Lost in Amber Light." For the first time in his life, he realizes he can grasp ways to assert himself and break out of a lifelong habit of supine passivity.

Drake is one of Grant's wannabe writers, but without hunger or ambition. His girlfriend Jill, like so many women characters in Grant, is made of sterner stuff:

She was two inches taller, even in her flats, her white shirt more snug than his, her white shorts cut high and loose, her hair against her tan a deep golden brown. A round face, a pug nose, a thin scar that ran from the corner of her right eye almost to her ear, making that eye seem almost slanted. She played basketball, swam, hiked in the White Mountains, and was reputed to have beaten up every boy on her block every year until she reached high school.

To add additional piquancy, Grant depicts Drake's mother as finding her way to her own control and self confidence. She reveals to her son that she has also ridden the Black Carousel, desperate to throw-off family censure about her failed marriage and low-wage job.

“Mom?”

“They picked at me,” she said bitterly, still smiling. “Like I was a chicken bone, leftover turkey. They picked me to death, and they wouldn’t stop.” A hand reached into the light and touched his chest, brushed it, pulled away. “He went away, the bastard, and they swooped in like vultures. They sat on me. They picked. Rene’s the baby, Wendall, she doesn’t know what she’s doing.” Her eyes closed. “I swear to God, Drake, I don’t know what I would have done if it hadn’t come back.”

He couldn’t move, could scarcely breathe.

She winked. “I took a ride, dear. Just like you did. On Tuesday, remember? He took me to the fair.”

Oh Jesus oh God.

“And you,” she said, “thought it was you, didn’t you?”

Couldn’t move.

Wanted to scream.

“Darling,” she said, almost crooning, “I’m your mother, sweetheart, I’m not stupid. And don’t look at me like that, dear. Don’t think you’re going to get away before I decide it’s time.” The hand again, patting his chest, dusting it, pinching it once. Hard. “Think about it. Stand there a little while and think about it.” Her face hardened, became sharp, inhuman. “I have quite an imagination, Drake. Don’t believe for a minute I can’t lose you too if it means losing control.”

She walked away slowly, humming, running a finger over the newel post as she headed for the kitchen.

Her shadow on the floor was of a woman, dancing; her shadow on the wall was cobra spreading its hood; the figure passing through the doorway was a vulture settling its wings.

The palpably erotic chemistry between mother and son, as each arrives at the threshold of their own autonomy, is elegantly shocking: Grant overstates nothing and there are no false notes. "The hand again, patting his chest, dusting it, pinching it once. Hard." is only topped in jouissance by "running a finger over the newel post as she headed for the kitchen."

"Lost in Amber Light" parallels in many points "I See Her Sweet And Fair," collected in The Orchard. There, single father Brett Gilman, desired by two adamant women and pursued by his teenage son's former girlfriend, is a man sorely in need of a visit to the Pilgrim Travelers' carnival. The orchard certainly never offered him control of his own life.

In "The Rain Is Filled with Ghosts Tonight," Grant begins by making use, as he often does, of used to be called the pathetic fallacy:

The house in the middle of the block between Poplar and Thorn was long and low and feeling its age....

"The Rain Is Filled with Ghosts Tonight" is a story about aging, the way growing old and losing connections with the living turn us into ghosts, haunting and being haunted, at the mercy of unbidden and often deceptive impressions from memory.

Kayman Kalb repeatedly meets with and runs from specters. Oxrun Station becomes a nighttown: face-offs and pursuits have the carnivalesque intensity of scenes in films like Carnival of Souls and Jacob's Ladder.

“Come with me, Kayman.”

Streetlights and house lights and the splash of rain; cold and a cold wind, cold skin, in a twilight that hid the sky but not the town around him; too weary to think, to find reason, to find something in his madness that would give him a clue so he could find his way back, to the house and Estelle and what the hell did it matter, Jesus God, he was tired. So goddamn tired. Everything about him, inside and out, ached, begged him to find a bed, demanded he stop moving.

And then a flash of anger that they had left him after all.

An old man alone.

Walking in the rain with a ghost that only proved how mad he really was.

“You know,” he said, and Flory’s head tilted; she was listening. His left hand flapped at his side. “I guess it really is like Ronnie said once — god, that was a long time ago — that the best you can do is hold on. There’s no stardom, no wealth, not much of anything but just holding on for people like me. Maybe you, too, I don’t know.” The hand stopped; the other one started. “I make furniture, you know. Pretty good stuff, too. It . . .” He squinted into the rain, no longer feeling it, no longer caring. “It just wasn’t good enough. It didn’t look like anything else, you know? It made itself sometimes, and it wasn’t . . .”

At Mainland Road he saw the fence of Pilgrim’s Travelers.

He stopped.

“You know that song, all those books, about doing it your way, the hell with what people think?”

“Come with me, Kayman,” she said, crossing over.

"The Rain Is Filled with Ghosts Tonight" is Grant at his coldest. Horrors cannot be expected later by Kayman: they come all at once. Whether the material everyday world is their stage, or solipsism is involved, Grant is content to have Kayman wait in equipoise.

The Epilogue to The Black Carousel is a continuation by the Prologue’s first person narrator, a faux "Charles L. Grant," as he and a few friends usher Deric Stockton on a nighttime walk. Ultimately their steps turn toward Armstrong’s farm.

I had a feeling we looked pretty damn drunk, and I laughed to myself.

Then Deric said, “What’s Armstrong’s farm?”

“It’s deserted,” Nina told him before I could answer. “On the other side of the highway. Some guy who used to live there a zillion years ago. Nobody knows why he left. There isn’t much left of it now — weeds, stickers, an apple orchard nobody will touch with a ten-foot pole, some fields mostly covered with new forest growth now.” She shrugged. “Not the most exciting place in the world.”

“So why are we going there?”

“Don’t ask me, ask him,” she said. “He’s the guide.”

I put a finger to my lips.

She slapped my arm. “Tell him, dope, before he runs away.”

I shook my head.

Deric’s patience was amazing.

At Mainland Road we paused for a moment, not waiting for traffic, just standing there a while so our vision could adjust to the glow from the sky. Across the way, the ditch was darker black, the high shrubs and thorn bushes more like a stone wall.

“I ain’t going to fly,” Callum grumbled as we crossed.

“There are ways,” I told him, and found a gap and led them through.

And once on the other side, Deric stopped me with a touch.

“Pilgrim’s Travelers was here?”

I nodded.

“I see.”

I knew what he was thinking — though moonlight and starlight weren’t their brightest tonight, it was more than clear, and would have been so in pitch black, that nothing the size of that itinerant carnival could have fit into the open space between the thorns and the orchard, and the trees that flanked them. Not even half. Not even a quarter.

There simply wasn’t any room.

And there were too many rocks, too many boulders, too many saplings and yearlings and old weeds and depressions and burrows and wildflowers. This place hadn’t been used since King George was in charge.

Nina stood close, fumbled for my hand and held it; hers was cool.

Callum followed Deric here and there, answering questions I couldn’t hear, staring at the ground, hunkering down and poking at the earth with a stick or a finger, standing, looking up, finally turning to me and waiting with his hands loose on his hips, looking every inch a cop demanding explanations.

There wasn’t much more I could tell him.

* * *

Holding on

A recurring figure in The Black Carousel is the phrase "Holding On."

Riders on the Black Carousel, no matter what they see at each turn, had better not let go. The carousel teaches its customers that living life is like having a tiger by the tale. Or something worse.

If Fran Lumbaird and Drake Saxton do not find death in the carousel’s counterflow reality effects, neither will they think themselves unmarked. The epilogue informs us Fran's family "were forced to move back to Cambridge when Neal lost his already tenuous job." Drake's predicament seems more problematic. His skills at holding on may work against him.

Jay

6 May 2024