"Deborah" (1929) by Josephine Tey (1896-1952)

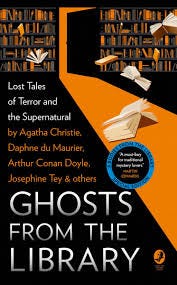

Ghosts from the Library: Lost Tales of Terror and the Supernatural (2022) ed. Tony Medawar

Readers unfamiliar with Ghosts from the Library: Lost Tales of Terror and the Supernatural may prefer to read these notes only after reading the anthology.

Josephine Tey (1896-1952)

We do not expect horror stories to be charming. Granted, many start out that way. "Wolverden Tower" and "Mr. Humphreys and his Inheritance" spring to mind. But these two examples eventually make their turn to terror. ("Wolverden Tower" is to my mind one of the strongest Yellow Nineties Machen stories not written by Arthur Machen).

But this is by the way.

"Deborah" (1929) by Josephine Tey begins with the beguiling of its narrator George and his friend Lizbeth.

In spite of the emptiness of the wide hearth the room had a pleasant look, very welcoming. It was, moreover, an authentic cottage interior. There were no Liberty cretonnes, no rush mats, no colour scheme. The curtains, as Lizbeth remarked afterwards, were made of flowered chintz at a few pence a yard, and the possibly valuable bits of china on the mantelpiece were cheek by jowl with the kind of tea-caddy a grocer gives away at Christmas and souvenirs of half a dozen watering-places. Nothing in the room had been placed there for its effect. Each article was there because of its value to the owner. And yet in spite of that—or perhaps because of it—the room had a charm that no arranged room in my experience ever had. And the rest of the house was the same.

We moved out of doors and stood looking at the place in a sort of speechless satisfaction. On one side the garden was bounded by a row of white lilac trees, heavy with bloom. At the back, rather close to the house, were aspen poplars—the kind that make a sound like rain when the lightest wind comes—and on the grass at the other side were Lizbeth’s crooked little apple-trees. By the road ran a very low hedge of box. A narrow brick path went up to the door, but not round the house. There was no back door, and the grass, unbroken by any flower-beds, grew close up to the walls. It was no show place, inside or out, but it had a most definite charm. All buildings have an atmosphere of some kind or other. ‘Laburnum Cottage’—for that was its prosaic name— had an air of primness. It wasn’t smug—not even complacent. But there was a happy well-orderedness about it. It both deprecated and disowned the tipsy notice-board. The unmown grass had the incongruous effect of dishevelled hair on a carefully dressed woman. And yet it wasn’t in its physical peculiarities that the primness lay. You can get an ordered effect with poplars or cypress or trimmed box. But lilacs are not exactly prim, and the laburnum at the gate was positively wanton. The primness hung in the atmosphere itself, somehow.

Of course the protagonists rent immediately. Doubts and second-thoughts are slow to accumulate.

Later on Lizbeth said, ‘How is it that none of the other tenants wanted to hang on to a little heaven like this?’ It was a question we had often asked each other, and we both turned to our visitor. On Mary Halkett’s face was the expression of one who sees a step just in time. It was gone even as I turned, and she said evenly:

‘Well, it’s a very lonely spot, and once summer’s gone, not so very attractive. Most of the tenants were the kind who like to go to a different place every year.’

Which seemed a reasonable enough explanation.

Eventually the couple tell neighbor and caretaker Mary Halkett that they will not return.

‘Oh, I’m so sorry!’ she cried. ‘So sorry! You’ve been the nicest people we’ve ever—You liked the place so much that I thought she might—But I was afraid back in July that you’d noticed. And she wouldn’t let up. You’re not angry, are you? There’s no harm in the cottage. Only the—the queerness.’

No "appointment in Samarra," no biters bit, no abomination of desolation, no vastation.

I drove down to Bognor in a dazed condition. As we sighted the sea, Lizbeth seemed to wake up from a trance. She gave a little amused snort and said, ‘Isn’t it ludicrous that in these days of shortage of labour we refuse to have anything to do with a cottage that dusts itself!’

* * *

The charm of "Deborah" is in Tey's faultless depiction of summer vacation landscape and weather -- interior and exterior.

....it would be difficult to find a snag in the perfect days we spent at the cottage. We would let the Halketts know when we were coming down and they had the place open, clean, and aired for us. They supplied us with milk, butter and eggs, chickens, ducks, and salads. The weather all the summer was the kind that leaves one in no doubt. We spent the long, brilliant days in the garden on the little patch of shaved turf, I working in a deck chair, Lizbeth supine in a hammock slung from the lilac trees. Little flaws of wind ran in a whispering patter through the aspen poplars and ceased abruptly as if afraid of being overheard. Our flowered Chintz flapped lazily at the yawning windows. Over the tops of the trees across the road the blue Sussex distances shimmered in the sun. In July, when London was a blazing furnace, we migrated altogether to Laburnum Cottage. It was then that the change in Lizbeth began. She grew listless and nervy. I blamed the long heatwave and wished that I could take her for a sea voyage, but a country cottage was the best we could do. She woke to animation sometimes when Mary Halkett would look in in passing, and would discuss with every appearance of interest our predecessors in the role of tenant, especially the former owner. I had the impression that the Halkett girl was not quite at her ease at these moments, and I wondered which of the tenants had been the undesirable one.

I like the phrase "Little flaws of wind."

Later in the summer, Lizbeth has developed some eccentric behaviors, and the weather reflects more impatient menace than the early July idyll.

....one evening at the end of July, after a grey, dusty day, sultry and full of the promise of storm, we arrived back from a short walk along the parched lanes. Lizbeth had gone in front of me through the open door and was standing apparently gazing down at the table where the evening meal was set.

‘Oh, I don’t like it!’ she said suddenly with such passion that it took my breath away.

The chicken salad on the table was one of her favourite dishes, but the best course was to humour her, I thought.

‘There’s some cold beef in the larder,’ I said. ‘Shall I get you that?’

To my surprise she turned with a little shaky laugh.

‘You prosaic darling!’ she said.

Then her smile died away. She came close up to me and peered half-searchingly, half-confidingly into my face.

‘Have you never noticed the queer thing about the house?’ And as I struggled for words in my astonishment, she added, ‘No, I suppose a man wouldn’t notice. Well, look at the room. There has been a wind all day and clouds of dust have been drifting over the garden. The doors and the windows have been open since morning, and there isn’t a speck of dust in the room! And it’s always like that!’ Her voice rose hysterically. ‘No dust anywhere!’

It's not Shirley Jackson-level hysteria, but given the social context, it's a temblor.

For a month I was so busy that we had no chance of getting away even at the weekends. And then, quite unexpectedly, I had a free Saturday and Sunday. It was hot and very much the fag-end of August in town, and I tentatively suggested the cottage. To my surprise Lizbeth, who had quite recovered her good spirits, seemed not only willing, but glad. I heard her humming as we packed, and I called through to her, ‘There won’t be time to let the Halketts know, but I don’t expect we shall starve.’

It wasn’t a pleasant journey down. The whole countryside was crying aloud for water, the wind was blustering, and pillars of dust that looked as high as the Nelson monument would rise in front of us and just as we reached their base would, deliberately it seemed, collapse on us. The hedge and the trees outside Laburnum Cottage were grey with dust and the grass looked shabby. Lizbeth went up to Halkett’s for the key while I tinkered with the engine before consigning it to the mercies of the garage-late-blacksmith in the village.

‘There was no one to be seen at Halkett’s,’ she said when she came back, ‘so I just took the key off the nail.’

I joined her at the door and went into the living-room with her.

Do you know the feeling you have sometimes on entering a room that it has just that moment been vacated? You didn’t see or hear a door closing, but you have the impression that someone went out as you came in. Well, there wasn’t another door to the living-room at Laburnum Cottage, but I most distinctly had that feeling....

"Deborah" is a quiet and contemplative story that tracks subtle shifts in worlds mundane and spectral. It charms, but a spell of tumult and wrongness lingers.

Jay