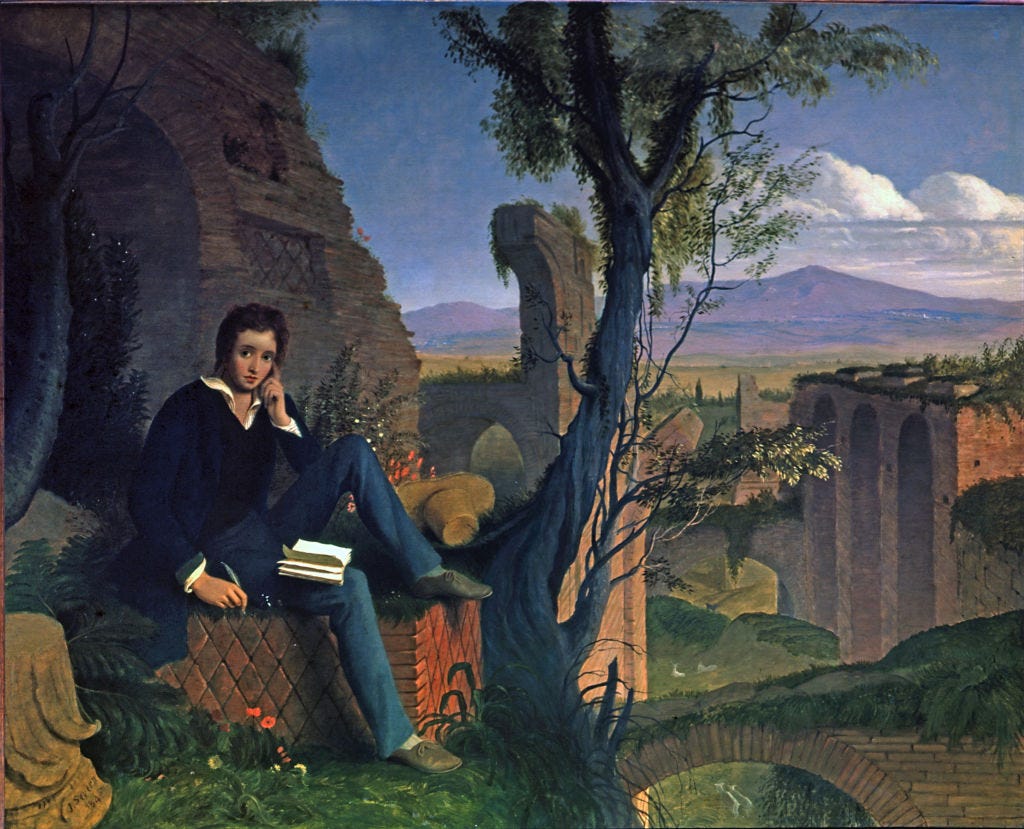

"Ghost Stories" of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

The Prose Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Vol. 2 [of 2]

Readers unfamiliar with The Prose Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley may prefer to read these notes only after reading the fragments discussed below.

Shelley's fiction fragments would fit the bottom of la cage aux folles, but it is hard to imagine a better use for them.

"The Assassins" (1814) is a promising beginning to what was clearly planned as a piece of ambitious scope. It would make a powerful novel depicting ruined Rome and the Jerusalem of crusader futurity. But only in the hands of Bulwer-Lytton or Gore Vidal.

The "ghost stories," resulted from table talk of Matthew Gregory Lewis, and are of historical footnote interest.

Geneva, Sunday, 18th August 1816.

See Apollo’s Sexton,[Matthew Gregory Lewis] who tells us many mysteries of his trade. We talk of Ghosts. Neither Lord Byron nor M. G. L. seem to believe in them; and they both agree, in the very face of reason, that none could believe in ghosts without believing in God. I do not think that all the persons who profess to discredit these visitations, really discredit them; or, if they do in the daylight, are not admonished by the approach of loneliness and midnight, to think more respectfully of the world of shadows.

P. B. S. continues:

....The tale was of a lady in Germany.

This lady, Minna, had been exceedingly attached to her husband, and they had made a vow that the one who died first, should return after death to visit the other as a ghost. She was sitting one day alone in her chamber, when she heard an unusual sound of footsteps on the stairs. The door opened, and her husband’s spectre, gashed with a deep wound across the forehead, and in military habiliments, entered. She appeared startled at the apparition; and the ghost told her, that when he should visit her in future, she would hear a passing bell toll, and these words distinctly uttered close to her ear, “Minna, I am here.” On inquiry, it was found that her husband had fallen in battle on the very day she was visited by the vision. The intercourse between the ghost and the woman continued for some time, until the latter laid aside all terror, and indulged herself in the affection which she had felt for him while living. One evening she went to a ball, and permitted her thoughts to be alienated by the attentions of a Florentine gentleman, more witty, more graceful, and more gentle, as it appeared to her, than any person she had ever seen. As he was conducting her through the dance, a death bell tolled. Minna, lost in the fascination of the Florentine’s attentions, disregarded, or did not hear the sound. A second peal, louder and more deep, startled the whole company, when Minna heard the ghost’s accustomed whisper, and raising her eyes, saw in an opposite mirror the reflection of the ghost, standing over her. She is said to have died of terror.

Shelley notes: "Lewis told four other stories—all grim."

My favorite, anticipating by nearly a century Saki and Jerome K. Jerome:

A gentleman on a visit to a friend who lived on the skirts of an extensive forest in the east of Germany, lost his way. He wandered for some hours among the trees, when he saw a light at a distance. On approaching it, he was surprised to observe, that it proceeded from the interior of a ruined monastery. Before he knocked he thought it prudent to look through the window. He saw a multitude of cats assembled round a small grave, four of whom were letting down a coffin with a crown upon it. The gentleman, startled at this unusual sight, and imagining that he had arrived among the retreats of fiends or witches, mounted his horse and rode away with the utmost precipitation. He arrived at his friend’s house at a late hour, who had sat up for him. On his arrival his friend questioned as to the cause of the traces of trouble visible in his face. He began to recount his adventure, after much difficulty, knowing that it was scarcely possible that his friends should give faith to his relation. No sooner had he mentioned the coffin with a crown upon it, than his friend’s cat, who seemed to have been lying asleep before the fire, leaped up, saying—“Then I am the King of the Cats!” and scrambled up the chimney, and was seen no more.

Harold Bloom has called Shelley "almost the Leon Trotsky of his day." Certainly this is correct insofar as we acknowledge Shelley as participating in a "permanent revolution" of the poetic mode of his time, which remains ours.

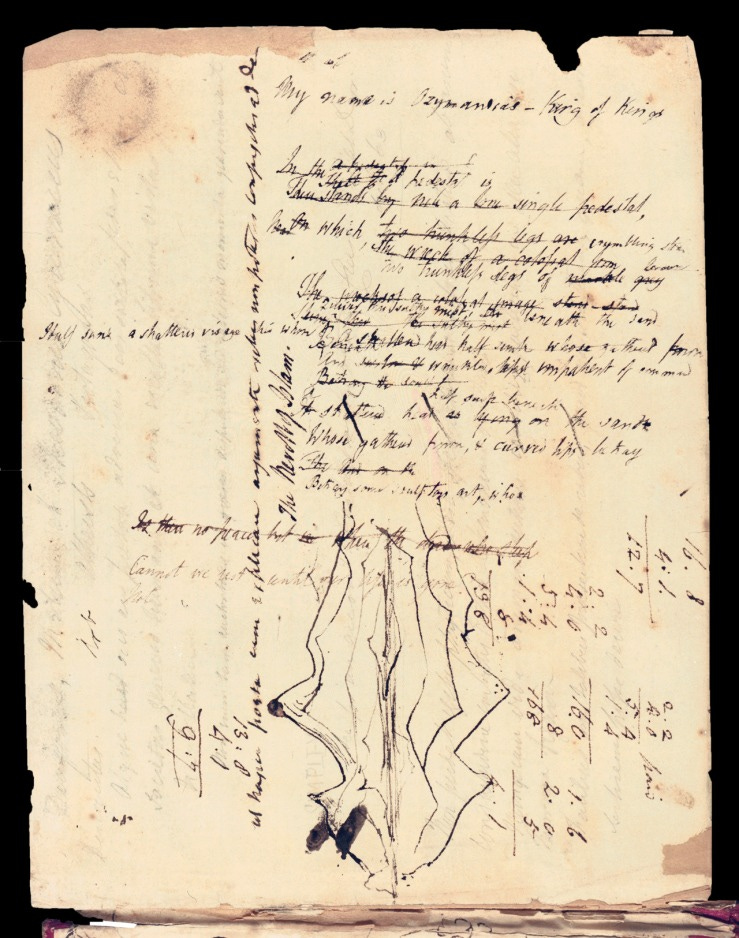

Shelley's recapitulation of Lewis's spectral stories would never be considered the poet's contribution to horror. For that we have the sublime cosmic horror of "Ozymandias." And "Mont Blanc," which anticipates Blackwood's "The Willows" and "The Wendigo."

Today for Shelley, as for Machen, Blackwood, and Lovecraft in the twentieth century: "The lone and level sands stretch far away...."

Jay