Readers unfamiliar with "Halloween Girl" (1982) by Robert Grant may prefer to read these notes only after reading the story.

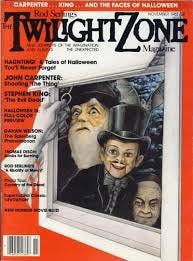

The splendid ceremony of laughing darkness

"Halloween Girl" tries wringing poignancy from confrontation with death as it separates a boy and girl united by mutual love of horror fiction and film.

The friendship had just happened, as things will when they must. Marcie’s family had moved to town a little more than a year ago, and Tommy, who had never thought much about girls one way or another, hadn’t paid particular attention to the new auburn-haired pupil with the eyes that wanted to give friendship but always danced away like a deer in a forest.

Then their fourth-grade class had to give oral reports on short stories, and when Tommy’s choice was “The Premature Burial” and Marcie’s “The Damned Thing,” the link was forged. After class he had found himself asking, “You like those kinds of stories?”

And so it had gone. A mutual interest—no, a feeling, a surging need for the fantastic, the ghoulish, the shadows that lurked inside shadows. Heedless of their classmates’ teasing (“Look who’s in love!”), they seemed always to be together. When a new horror movie came to town, they would be side by side in the candy-scented darkness on Saturday afternoon, and they haunted the fantasy-jammed wonderland of the comic book racks. But their favorite province, their kingdom, was the hushed aisle of the library, where they fearlessly ventured into the dark regions of the grown-up section. For there lurked Frankenstein, Dracula, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and their brethren.

When not unearthing what netherworldly treasures their small town had to offer, they would be at their hidden sanctum, behind a ramshackle storage shed in Tommy’s backyard. There, in a small shaded spot, invisible to the dull outsiders, they pored over their ghastly booty and poured out their souls, both emptying their own magics, the shared wonderful strangeness that was theirs alone while the rest of the world threw balls, kicked tin cans, and went on its own grey way.

“Boy, they really goofed in that scene where the vampire went out in daylight!”

“No lie!”

And:

“I think ‘The Call of Cthulhu’ is better because you have to imagine what the monster looks like. It’s eerier that way.”

“Yeah, but ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’ has a better ending.”

And:

“Boy, we’re gonna make a haul this year! Last Halloween my bag was nearly overflowing with candy bars and caramels and bubble gum and licorice and—”

“Licorice, ugh! I always throw mine away.”

“Marcie! How could you! Well, this year you can throw it into my sack.”

And so it went. Afternoons flew by on bat-wings, riding a high howling wind of imagination that bore them above the plain white houses and the dismal green classrooms and the endless flat grasslands.

Now the bond had become more intense, more centered as the Night of Nights approached. There were so many things to do, so much making and searching and assembling so that the splendid ceremony of laughing darkness would be right in every detail….

Some kids enjoy the Halloween season for its ghoulish associations with physical death and burial; it's fun to try such emotions and thought experiments on for size. Tommy and Marcie, fourth grade best friends, enjoy the process and the endless distraction of kibitzing about it.

For Tommy, though, an all-but-crushing preview of adulthood approaches.

The air was surprisingly warm, a vagrant echo of a summer that had gone away somewhere. Yet there was no question that the weather wasn’t young anymore. Beyond the trees, beyond the horizon, something chilly and grey lay waiting....

[….] He wasn’t sure from what he was hiding, but it was something beyond his control, something fearsome but perhaps more sad than mean.

He tried not to imagine.

In the story's final pages, Grant's authorial voice, angling for a semi-formal style imitating the rudimentary emotional world of ten year olds, stumbles and turns over-emphatic and faux-Bradbury poetic. The final line is clumsily foreshadowed, and cheapens the seriousness the story has achieved in spite of infelicities.

Jay