Readers unfamiliar with In Ghostly Company may prefer to read these notes only after reading the collection.

They would have, no doubt, preferred some cheerful neighbors, but Mr. Roberts was positive in his assurances that there was no one in the neighbourhood whose acquaintance would be of interest to them.

-- “Brickett Bottom”

In Ghostly Company (1922) by Amyas Northcote is not a touchstone collection of horror short stories. Several of its stories, however, do compete with the finest stories published in the early 1920s. One or two, in fact, look further forward than that, given their stylistically emergent handling of story elements that resist resolution and, ultimately, logical understanding.

Contrary to Amyas Northcote’s current Wikipedia entry, In Ghostly Company (1922) is not exclusively a book of Jamesian or antiquarian short stories. They most resemble stories by E. F. Benson: tight-focused, unsentimental, acute in social observation, and shocking in the reticence of their narrative voice. One or two employ material usually pigeonholed as Machenian (“Brickett Bottom,” with its depiction of what critic Thomas Kent Miller calls “Machenean perichoresis”; and “In the Woods,” which begins as a more banalized retelling of “The White People”), but only one In Ghostly Company story employs antiquarian elements.

The story “Brickett Bottom” haunts me daily, and has done since I first read it. I have written about it here and here.

“Mr. Kershaw and Mr. Wilcox” is one of a thousand short stories about business partners who have a falling out. In fiction, do such plot contretemps always result in murder? In real life? Does it -- at long last -- for Mr. Kershaw and Mr. Wilcox?

As noted above, “In the Woods” is a story that carries forward and de-stranges some elements familiar to readers of “The White People.” It begins and ends with a sighting of its heroine by another character who plays no direct part in the action. This is an arresting choice by Northcote, framing and further distancing his protagonist.

Northcote pays careful attention to the social alienation of the character, and the way this can entice a young woman away from everyday life.

[....] Little by little did she become absorbed into them; she dared not as yet visit them at night, on account of the certain annoyance of her father, but by day she almost lived in them, and her belief in the souls of the trees grew stronger and ever stronger. She would sit for hours motionless, hoping, believing, that at any moment the revelation might come to her, and that she would see the Dryads dancing, and hear the pipes of Pan. But there was nothing. ‘Another day of disappointment,’ she would cry....

Ultimately, Northcote provides a narrow escape for his protagonist. Unlike Machen's diarist, there is no need here for recourse to the poison bottle.

In “The Late Earl of D.” a young lawyer is dispatched to a remote house to review documents. While in the library, and looking out the window, he sees reflected behind him the events surrounding the death of the previous earl. It's a minor drama, but unsettling in its use of disability as an uncanny element.

If one story in In Ghostly Company is antiquarian horror, it is “Mr. Mortimer's Diary.” It details – via witnesses and diary – the last eight days of a scholar's life. Mortimer's career was based on

[....] a proof of certain close relationships between Etruscan and Egyptian artistic works. This essay provoked a sharp controversy which, besides moving along the lines common to most battles between scientific experts, was marked by a regular attack on Mr. Mortimer by a man named Bradshaw, an assistant master at an obscure Yorkshire school. Mr. Bradshaw, in a letter to the Times, claimed to be the real discoverer of the objects on which Mr. Mortimer based his article and roundly asserted that Mr. Mortimer had stolen them from him, and had also purloined from him the genesis of the ideas which he was now presenting to the world as his own....

[....] With this preamble the diary may now be quoted in full.

July 8th. “I was the subject to-day of a singular hallucination: I believe the spiritualist jargon describes it as clair-audience. I was in my rooms dressing to dine out with Lady L. when I distinctly heard the voice of James Bradshaw saying, ‘The day of reckoning will come soon.’”

Mortimer later learns this clair-audience coincided with Bradshaw's death.

Northcote does a very tidy job depicting the daily life of a well-to-do bachelor scholar: his routine, his club, et cetera. The reader joins with him in relishing the unraveling of this world.

“The House in the Wood” is the only Northcote story that takes place in North America. The framing scene is done as the small talk of traveling salesmen on a Chicago to New York express.

At this point, I could not help but recall this scene:

The narrative turns on Northcote's steadfast and upstanding salesman protagonist sharing a horse cart with the paymaster of a mine in the Iron Range of Lake Superior. Known to carry cash when he travels through the area once a month, the paymaster fears robbery and murder. The two men are faced with just such a situation in a lonely farmhouse. It's a dramatic tale in chiaroscuro, filled with menacing faces. And a heaven-sent warning.

The only Northcote story to touch on the Great War, “The Steps” is drawn from the papers of “one of our leading medical men, who, during the late war, attained considerable eminence in the treatment of nervous diseases and affections of the brain.”

Northcote provides excerpts from the nerve specialist's case notes:

“‘[....] You know I told you I was troubled by footsteps coming from a distance and stopping well away from me. They did not come often then, but they do now; they come all the time,’ she went on, ‘and come clearer and louder and they come nearer. Nearer, nearer, they come close to me and, oh God, one day he will reach and touch me and then—” She stopped for a moment and I was thinking what I could say to reassure her when she suddenly caught hold of my arm.

“‘There they are now,’ she cried. ‘Listen, they are coming down the passage. Listen, listen.’

“Her distress and agitation were so extreme that I could not control myself for a moment and we both sat in dead silence listening. I am not a nervous or imaginative man and in my cool moments I am sure I was mistaken; but at that instant I could have sworn that I heard a footfall on the oilcloth outside….”

“The Young Lady in Black” begins with the initial narrator informing us

The following story is one of actual experience, and while not a tale of horror and woe, like the typical ghost story, still is interesting as opening up for consideration the question whether, after the death of the body, the spirit is able to carry on and bring to a more or less satisfactory conclusion some task commenced in the flesh....

The second narrator, a society portrait painter, begins his story on a busy day in his studio. A woman “dressed entirely in black and [wearing] a heavy black veil,” arrives to commission a portrait of herself. She informs the painter she will not return for it, but gives him a delivery address.

The remaining two-thirds of “The Young Lady in Black” dramatizes several strange encounters as the titular character works to spur the narrator to complete her commission. The story's opening has already reassured the reader it will be “not a tale of horror and woe.” But I have to wonder how E. Nesbit would have approached the idea. Or H. P. Lovecraft, if his Pickman accepted a commission from far below Boston?

“The Downs” is a first-rate folk horror short story. It contains everything a fan of that literature could hope for: a solitary walk in open country at night; a feeling of others drawing closer in the dark; sightings; aural manifestations; a climactic run for safety, culminating in a local’s explanation.

“The Late Mrs Fowke” is a droll thriller infused with biter-bit schadenfreude. It is a fine mixture of suspicion/skepticism, interior/exterior, sadism/masochism, misanthropy/misogyny.

The trouble starts when Reverent Fowke secretly follows his new bride to the high moor.

Mr. Fowke watched absorbed. Gradually the dance grew quicker and wilder and the chanting louder, the whirling forms flung themselves into grotesque attitudes and shrieked ejaculations, the meaning of which Mr. Fowke began dimly to divine though the words were strange. Suddenly they were silent and still and at the same moment Stella rose from her seat and, throwing back her hood and turning towards the summit of the altar, began in her turn to take up the chant. As she sang and bowed towards the topmost stone, her face and figure seemed transformed. In the flickering firelight and pale moonshine she seemed to grow weirdly and horribly beautiful and to grow statelier and taller in her person. Slowly, too, as the song progressed the horrified watcher saw another change. A grey cloud formed on the summit of the altar, diminishing, thickening and turning into a Shape, a Shape of evil and fear. The silent group by the fire once more broke forth into wild gesticulations and cries, Stella prostrated herself, the Form on the altar grew clearer and with a cry of horror Mr. Fowke turned away and rushed madly across the moor.

I previously celebrated “The Late Mrs Fowke” here.

“The Picture” is the first horror short story I have read that deals with ramifications of the 1848 revolutions in Europe. “The Picture” takes place in Hungary. It details consequences over several generations for the Pavlinski family, one of whom led the 1848 assault of the local castle of “wicked Count W.”

“The Picture” recalls some historical novellas by Gerald Kersh, as well as similar themes hinted-at in Simon Raven's 1980 thriller The Roses of Picardie.

“The Governess's Story” is one of Northcote's few strictly “haunted house” tales. It resembles in miniature some aspects of “The Turn of the Screw,” if that masterpiece were thinned-out, compressed, and remade as a wholly supernatural story of wrongful death and comeuppance.

Alas, it does little for the reputation of stepmothers.

“Mr. Oliver Carmichael” is a de-familiarized occult melodrama of reincarnation and love across the ages.

I previously wrote about it here.

* * *

In Ghostly Company is worth the reader's time and attention for the pleasure of reading its tonally and stylistically emergent modern stories: “Brickett Bottom,” “The Late Mrs Fowke,” and perhaps “The Downs.” More derivative residual tales like “The Governess’s Story” are certainly worth reading once.

Jay

1 February 2024

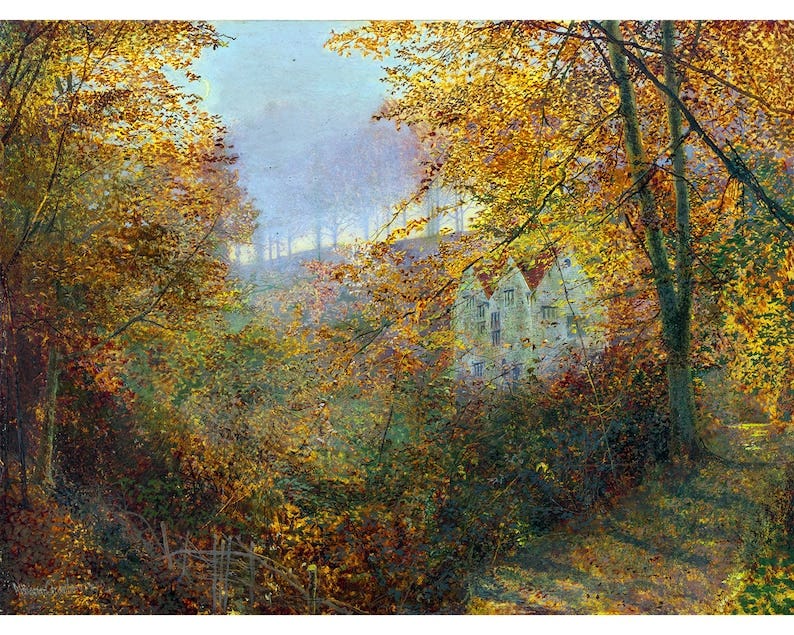

Art: John Atkinson Grimshaw A House in the Clearing 1870 / English