Readers unfamiliar with Strayers from Sheol may prefer to read these notes only after reading the stories.

Strayers from Sheol (1961) by H. Russell Wakefield, in the 1999 Ash-Tree press edition, contains short stories and novellas spanning three decades. They are of uniformly high quality both as works of fiction and works of horror. Some feature traditional ghosts (in the pre- and post-Jamesian senses), others provide more disturbing spectral disturbances for the protagonists.

The Triumph of Death (1949)

"The Triumph of Death" is a stunning mid-career short story. It looks back to previous genre milestones knowingly, but never lets this self-consciousness interrupt its gripping authority.

Within a small compass, Wakefield depicts a benighted house and its infamous multi-generational family of sadistic owners. Ultimately, the last member of this family is so efficient in inflicting terror on her latest maid that she seals her own doom.

Such appointments-in-Samarra are always satisfying.

Ghost Hunt (1948)

In "Ghost Hunt" Wakefield works hard imbricating a contemporary media (here: radio) with an older frantic narrative voice once attributed to diaries and letters.

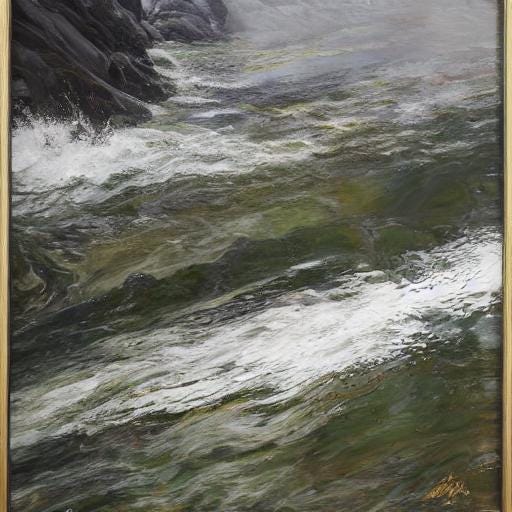

"Ghost Hunt" is one of several Wakefield stories in which a river plays a part. In the essay "Farewell To All Those," Wakefield explains:

Why was I persuaded into this arduous (ghost stories are very difficult to write) and unremunerative game? I am a skeptic by temperament, though not, I hope, a wooden one, and the skeptical temperament is essentially a fair, open-spirited one, ever avid to examine and, if necessary, to accept evidence adverse to its creed . And I received such evidence during two weekends spent in a superficially charming and harmonious Queen Anne house about a mile and a half from Richmond Bridge. I mustn’t locate it more precisely because— and it is a significant fact— even the most rampant unbelievers often refuse to live in a reputedly haunted house.

And I can assure them they are very wise.

I visited this house in 1917, and during the previous thirty years it had known five suicides—the old gardener, strictly against orders, blurted out this ominous record in his cups, and it was verified. One had hanged herself in a powder-closet. One shot himself in the tool-shed. The others had drowned themselves in the river about a hundred yards away, always, it was said, at dawn. And now mark this! About a year after I went there, the valet of a famous nobleman also drowned himself in the river at first light. He was seen running down the path as though a fearful fiend were hard upon his heels and plunging in to his death. I think you’ll agree that gives one somewhat somberly to think....

The radio commentator who narrates "Ghost Hunt" fills in the background:

[....] I used the expression ‘suicides in and from it’, because while some have shot themselves and some hanged themselves, no less than nine have done a very strange thing. They have risen from their beds during the night and flung themselves to death in the river which runs past the bottom of the garden some hundred yards away. The last one was actually seen to do so at dawn on an autumn morning. He was seen running headlong and heard to be shouting as though to companions running by his side.

By the story's end, the narrator has become so disoriented he seems giddy at the prospect of joining the house's permanent population:

....You want me to go to the river, don’t you? Ha! Ha! Now? Will you come with me? Come on, then! To the river! To the river!

The Third Shadow

Many well-known Wakefield stories are home-counties domestic: personal crises of renters and property owners , of spouses and lovers, of friends and colleagues. But Wakefield knew how to wring changes, as well. "Varying the mixture," as P. G. Wodehouse referred to his own similar procedures.

"The Third Shadow" is a good example. A retrospective story about how a husband freed himself from his wife, it is told in conversation between two climbers who knew him, and refer to him only as "Brown."

He was a smallish fellow, though immensely lithe, active, strong, and tough. She was not far short of six feet and tipped the beam at one hundred and sixty-eight pounds, mostly muscle. With what suicidal folly, my dear Bill, do these infatuate pigmies, like certain miserable male insects, doom themselves with such Boadiceas, and how pitilessly and jocundly do those monsters pounce upon their prey! This particular specimen was terribly, viciously, “County”, immensely handsome, and intolerably authoritarian. Speaking evil of the dead is often the only revenge permitted us and I have no intention of refraining from saying that I have seldom, almost certainly never disliked anyone more than Hecate Quorn. Besides being massive and menacing to the nth degree, she was endowed with a reverberating contralto which loaned a fearsomely oracular air to her insistent spate of edicts. Marry for lust and repent in haste, the oldest, saddest lesson in the world....

Opening with climbing lore about a third man sensed and sometimes seen by two climbers roped together and traversing demanding heights, "The Third Shadow" is leavened with mordant wit.

‘She demanded that he should at least attempt to teach her to climb, and females of her build are seldom much good at the game, particularly if they are late beginners. She was no exception, and her nerve turned out to be surprisingly more suspect on a steepish slope than her ghastly assurance on the level would have suggested. Poor Brown plugged away at it, because he feared, if she chucked her hand in, he would never see summer snow again. He did his very desperate best. He hired Fritz Mann, the huskiest and best-tempered of all the Chamonix guides, and between them on one searing and memorable occasion they shoved and pulled and hauled and slid her on feet and rump to creditably near the summit of Mt Blanc. She loathed the ordeal, but she refused to give in, just because she knew poor Brown was longing to join up with a good party, and have some fun. I need say no more, you have sufficient imagination fully to realise the melancholy and humiliating pass of my sad friend. And, of course, it wasn’t only in Haute-Savoie and Valais she made his life hell, it was at least purgatory for the rest of the year; his was eternal punishment, one might say. A harsh sentence for a moment’s indiscretion!’

Wakefield excels in demonstrating his mastery of such situations: the contretemps and reversals that sometimes lay waste to the lives of foolish or unlucky people.

The Gorge of the Churels (1951)

Children, ponds, streams, and rivers do not mix. Particularly east of Suez, where "The Gorge of the Churels" takes place.

The gorge -- or something within its confines -- is a mesmerizer and enticer of children. Colonial parents of course dismiss the local warnings.

Mr. Ash's Studio (1932)

A recurring motif in Wakefield, and the UK ghost story in general: cheap rent and the reason for it.

Mr. Horrocks, a writer whose fiction includes ghost stories, abandons an old apartment when noisy street repairs draw near, and rents a studio once occupied by a painter.

[….] There appeared to be two rooms, as a matter of fact, for there was another door at the far end. The place was lit by three high windows. It smelled rather fusty and there were patches of damp on the distempered There appeared to be two rooms, as a matter of fact, for there was another door at the far end. The place was lit by three high windows. It smelled rather fusty and there were patches of damp on the distempered....

Writers should beware landlords who claim to know and admire their work.

Woe Water (1950)

Readers known pretty quickly they are in Wakefield country, where every brittle-voiced diarist is unreliable:

Oct. 3rd: At last! What a huge relief to be away from all that foul publicity, the brutally cynical reporters, the cruel animal stares of the mob, those hard-eyed detectives, hoping to get their hands on me, and all the bestiality I’ve been through during the last month. This house is, of course, much too big for just Barratt and me, but I was in no mood to be selective and took the first more or less suitable place that offered. One thing, my privacy will not be violated here. We are two trespassers....village and the grounds are extensive and well wired-in. I shall be merciless to trespassers....

Alas, renters of property on Woe Water had better be prepared. The narrator gets an indication of this when old Carlman, the gardener, takes him on an orientation tour.

'....when there is a body within it, it takes the look of blood, and the body troubles the water while it is lying within it, troubles it for seven days, and on the seventh day the people come to meet and greet the dead man, and his sinful body comes up white as snow and picked clean of its evil flesh.’

Some of Wakefield's early stories feature blasé or unobservant protagonists who do not realize until too late the property they have purchased, rented, or are managing is a killer. (Examples: "The Red Lodge," "Seventeenth Hole at Doncaster," and "Lucky's Grove.")

At mid to late oeuvre, Wakefield began cross-hatching hints of connection beyond rent between locations and protagonists.

(Ben Mears would be an early Wakefield man; Jack Torrance, one of the late.)

A Kink in Space-Time (1948)

[….] Those in my state are terribly lonely. If they are even worse than I am, perhaps their fate is easier. They are segregated with their sorry kin, it’s true, but they are not so isolated. Of course I have friends but I will not inflict myself upon them, for I know that nothing is more physically destructive than contact with a tainted mind. Only the hardiest or the most callous can endure such connection. The higher, more sensitive, shun the mentally sick, for it is always their recessive horror that they may have to call them Brother one day. The sanity of all men, and the sanest know it best, is balanced on a razor’s edge, and any weakening will allow the virus of madness to take hold....

Like the Rev. Mr. Jennings, Wakefield's Sir George Maskell reports with growing hopelessness on his slide into insanity. But is it Maskell who is disordered, or the universe he observes in everyday life?

Messrs. Turkes and Talbot (1932)

Commercial greed and murder in the publishing game. Something unpleasant secreted in a small domestic flat above the business offices. Wakefield, who started in publishing, does an outstanding job delineating the higher and lower within the firm, and all the genteel illusions that get ground-up by iron economic necessity.

As for the wages of working late at the office after dinner:

[….] Mr Turkes was lying in his night-shirt on the floor by the bed and he was rocking gently on his shoulder blades. His hands were at his throat and his tongue—well, young Bob had never realised before what a quite large thing was the human tongue.

"Immortal Bird" (1961)

A sharp-elbowed look at professional jealousy on the higher slopes of math.

Our narrator is a sensitive from youth: "I don’t think I’m simply and solely a maniac, hag-ridden by subjective, Bedlam hallucinations."

He covets the office of "Regius Professor of Pure Mathematics at the Metropolitan University in London," but the current holder of the position, long past retirement age, shows no signs of actually retiring.

There any echoes of "The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral" stop. Told in first-person, "Immortal Bird" puts the reader's nose right down in the who, what, when, why, and how of a disturbed personality facing the moire of professional and supernatural consequences after finally succeeding to the cherished post.

[….] I was disconcerted to observe the birds had formed a circle on the lowest level and were steadily moving up towards me. I saw, too, the flash of a snow-white wing. I cannot write excitingly and ‘dramatically’, very few scientists can. Therefore I am unable to convey my feelings as I watched that—I nearly wrote ‘cortege’—and then I nearly wrote ‘ceremony’ (a fact which would, I think, have interested my old and dear friend, Freud), that company of birds approaching; knowing that in about four minutes they would have reached me.

The Caretaker (1961)

A vignette of carefully executed menace, "The Caretaker" is a raw and bloody revenge story as seen by an onlooker.

"Four Eyes" (1961)

The plight of second husbands is explored:

‘Fancy that!’ he exclaimed. ‘I shouldn’t know they weren’t my own, and they fit perfectly, too. Curious, because I should have said Jim’s head was quite a different shape from mine. What a stroke of luck. That has saved me about fifteen pounds! I suppose,’ he added in a would-be jocular vein, ‘some people wouldn’t care so much about wearing a dead man’s specs.’

‘How utterly ridiculous!’ said Bella tartly. ‘When you’re dead, you’re dead. What are you supposed to do with them? Bury them in the coffin with the body! That ’ud be a stupid waste of money.’ Bella didn’t believe in wasting money.

The Sepulchre of Jasper Sarasen (1953)

‘....Murdering whom?’

‘ ’Is wife and four kids, sir. Took ’em out for a row on the river, it seems. Never let ’em learn to swim. Then ’e tips the boat over and swims ashore ’isself. This gent I’m telling you of said ’is old man was sure Sarasen was guilty, dead to rights. ’E ’ad good reasons to do it, to marry a very rich woman. ’Owsoever they couldn’t quite pin it on ’im, and as I said, ’e got away with it. But it didn’t do ’im much good, it seems, for very soon after ’e was found dead ’isself in ’is ’ouse, though this gent said it was a bit of a mystery what ’e died of. Well, that’s what this gent told me, but ’e talked so fast it was ’ard to follow ’im.’

‘I see,’ said Sir Reginald slowly. ‘Nasty little story. And is his the sixth coffin in that sepulchre?’

The Middle Drawer (1961)

Mr. Skelt's home has become a hurricane's eye of paranormal activity since the death of his wife. On the morning he learns authorities have exhumed her body, the storm reaches force five.

‘Look here, Arthur, we were lovers before she died. She died very soon after. . . . There’s a most foul smell in here!’

‘Smell? What sort of smell?’

‘Of rottenness, mould, and death, death! Oh, I hate this house, it terrifies me! I could never live in it!’

‘Don’t be hysterical. You won’t have to live in it. I’ll move when we’re married. It oppresses me, too.’

‘You never show it.’

‘I am master of myself. This room always smells a bit damp.’

‘But not like this.’ Her voice rose hysterically. ‘Oh, Arthur, why have they dug her up? Will you swear you did nothing to her —ever?’

‘It’s a disgusting question,’ said Skelt angrily. ‘Of course I swear it.’

The house quivered, the windows hammered, the drawer shot forward.

‘God! What was that?’ exclaimed Dulcie.

‘Something passing in the street, I suppose.’

‘I’ve never known it happen before like that,’ said Dulcie, frowning. ‘What are you going to do?’

‘Just close that drawer,’ said Skelt.

.‘But why? Why? Why d’you want to close it?’

‘Dulcie, are you losing your senses? Pull yourself together,’ said Skelt raspingly.

‘It’s this awful shock. It’s all over the town!’

‘Where did you hear it?’

‘Mr Rogers, the chemist, told me. They’ve been to his shop.’

‘The police?’

‘Yes. Going through his books.’

‘Let them,’ said Skelt roughly. ‘They’ll find nothing there.’

Dulcie suddenly screamed, and put her hands to her face. ‘Mary!’ she cried. ‘I saw her at the window—in her shroud!’

Monstrous Regiment (1961)

A young man, an asylum inmate, recalls his mother's death and his molestation at the hands of a nurse hired to care for him. It's a grim topic, and Wakefield's authorial voice in "Monstrous Regiment" is free of the typically jocund tone found even in his grimmest stories.

Wakefield does not flinch or dissemble, handling his theme frankly.

Connie took me to our bedroom and undressed herself and me. Then she took me on her knees and fondled and kissed me. She held me tight to her and I could feel how strong she was. ‘You’re a very naughty little boy, aren’t you, Claud, but you’re also a very beautiful little boy and I adore you already. You’re going to be my little boy entirely, d’you see? I’m not going to slap you because your daddy told me to, but I shall slap you, and very hard, when I think you deserve it, and that’ll be whenever you disobey me. If your daddy asks you, you’ll say I hurt you a lot, won’t you?’ Her tone was sharp and commanding.

‘Yes, Miss Courtney,’ I said, much relieved.

‘You’re to call me Connie. When we’re alone, Connie, darling. D’you understand?’

'Yes, Connie, darling,’ I said.

‘That’s right. You’re a clever little boy,’ and she strained me to her again. ‘Are you going to love me, Claud?’ she asked, bringing her lips to mine.

‘Yes, Connie, darling,’ I said, and in a sense it was already beginning to be true.

Even these scenes appear tame once the specter of Claud's mother returns during his teenage years to inspire him to escape Connie.

[….] She stood before my bed and gazed into my eyes. I knew her first command was, ‘Fight! Resist! I am fighting for you. I shall never leave you till we’ve won!’ My mother knew there was only one solution....

One day I was reading the paper. My mother was there. As my eyes overran the print I suddenly paused at a small paragraph and could not move my eyes on from it. It told of a girl who was killed by an electric stove falling into her bath. I read this during a bitter December spell. (Before a man goes to the electric chair the executioner damps the sponges inside the electrodes. I was to be Connie’s executioner. ‘Each man kills the thing he loves.’ The bow of Ulysses should have twanged for Penelope!)

"Monstrous Regiment" depicts real tragedy, and its finely folded supernatural element underscores the narrator's waxing psychological crisis. It is a real aesthetic accomplishment.

The "Uncollected Stories" section of Strayers From Sheol contains four stories published after that 1961 Arkham House edition appeared. Each shows Wakefield pushing himself as a writer. New topics and predicaments are explored; new points of view or narrative idiosyncrasies are tried on for size.

The Animals in the Case (1962)

Jealousy of pets over their owner's infatuation with a one-eyed duck in "the big lake in Regent’s Park."

[….] His inordinate love of animals, so often characteristic of haters of mankind, was considered by his father to be morbid, and he warned him thus, ‘Between a man and the most developed animal there can be only the most limited understanding. So do not treat them as though they were a lowly brand of humanity—it confuses and upsets them, and can make them dangerous, as that intuitive genius, Kipling, so brilliantly revealed.’ His son took less heed of this sage advice than it merited.

The Last Meeting of Two Old Friends (1964)

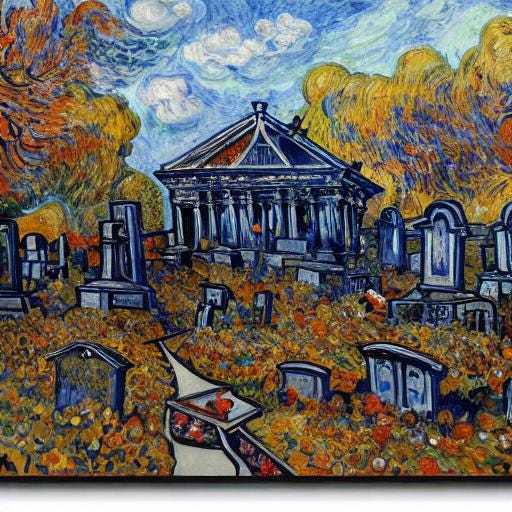

"The Last Meeting of Two Old Friends" starts out as an enjoyable riff on "Count Magnus." But it develops into one of the strongest stories in Strayers From Sheol, perhaps better than "The Triumph of Death."

Dikellian, a wealthy, middle-aged, newly married historian living in London, takes up walking. A large nearby cemetery looks like the ideal place. Alas, he quickly departs his usual circuit route and starts inspecting dates on headstones and mausoleums.

One, which suffered Blitz damage and is still unrepaired, has a deeply corroded copper panel:

[….] The big middle panel was dominated by one, clearly the same, person, displayed full length in profile. The figure was crouching, rather as a runner leans over his mark just before the starting pistol sounds. Its guise was, however, far less innocent and suggested stealthy motion in implacable pursuit of some prey which, perhaps, was in fatal ignorance of its fearful peril and that Death was on its trail. It moved Dikellian more than he cared to admit. ‘What’s it all about?’ he murmured in half-mocking perplexity, only half, because from first to last he was never quite candid with himself about his attitude towards that plaque, which frailly contributed something to the obstinacy with which he devoted himself to it. He was never at psychic peace with the thing. He now transferred his attention to the bottom panel—to receive a total rebuff. It comprised merely some lines of script, entirely illegible....

Dikellian eventually bribes some information out of a warden.

‘Well,’ grunted Dikellian, fishing out a brace of half-crowns and handing them over, ‘I hope I get my money’s worth.’

‘You’ll have to chance that,’ replied the Ancient, spitting on and pouching them. ‘See; completely pleb!’

‘Self-pity’s half your trouble,’ snapped Dikellian. ‘Proceed and earn your obols.’

‘Okay. Well, the yarn is that once upon a time, say a hundred and twenty years ago, there was a Jack the Raper living near here in a big house, somewhere, I take it, about the top of Fulham Palace Road. He was as rich as he was wicked, and he is said to have forced his servants to waylay young birds, whom he first knocked-off and then tortured to death. He was never accused of any of his crimes, but after his death his servants gave the show away and a number of bodies were found on his estate.’

‘Was he buried in the catacombs?’

‘Yeah. However, the relatives of his victims were determined to see some justice done, so they put up that tablet, though no one can read what they inscribed on it. Long ago that section was filled in. I understand it was considered “unlucky”—and with good reason. Along comes Adolphus and opens it up again. Well, believe it or not—it’s still unlucky.’

‘How d’you mean?’

An old scholar friend of Dikellian is able to decipher the copper's inscription.

From that point, "The Last Meeting of Two Old Friends" veers from pleasing-terror cemetery hide-and-side to something more macabre involving friendship, jealousy, and sudden death.

"The Last Meeting of Two Old Friends" is a great horror story, worth seeking and reading tonight.

* * *

Death of a Bumblebee (1967)

The Blitz also casts its long shadow over another solid uncollected story: "Death of a Bumblebee." To say it is a story about fate, predestination, or the appointment-in-Samarra doesn't do justice to Wakefield's craft.

'[….] We will expect you to luncheon on Saturday. Oh, one other point: she seemed rather reluctant to be hypnotised.’

‘Very intelligent, dominating women always are. I’ll try not to introduce the word when I’m in session with her. Often I can hypnotise them sufficiently without them being aware of it.’

‘Very well,’ said Carneby, rising to his feet. He paused. ‘Tell me candidly; there is said to be clairvoyance in her family and she’s certain that she has inherited it. Now, do you think that is all nonsense, that there’s no evidence anyone possesses any such power, gift—whatever you like to call it.’

‘Most certainly not. It is established beyond doubt, though, I may say, I never tell my patients so. I should have thought you as a literary man would have realised that.’

‘I don’t see why, it’s an extremely evasive business. I didn’t really expect you to say that.’

‘The occult in all its aspects covers an immense field of phenomena,’ intoned Sir Webster. ‘I only wish I didn’t believe in any of it, it’s a great nuisance in my work, a constant irritant and mischievous interloper.’

Appointment with Fire (1971)

Most readers probably share a caricatured view of Wakefield as a sub-Jamesian writer of English ghost stories . But Wakefield clearly never stopped pushing his skills, probing and depicting motifs and milieus that interested him.

These handful of late stories might have been a source of pride for a man laid low by liquor, who spent his days selling girdles or working as a doorman.

"Appointment with Fire" certainly features A new type of character in a new commercial arena: the Cockney Jewish gangster.

Wakefield, as even casual readers know, freely expressed all the shibboleths of racism and sexism that thrive within the middle class political consciousness under capitalism. Jew-hate was certainly another prejudice freely articulated:

[….] His [Mr Nathaniel Marks] body was gross and shapeless and his face shapeless and gross, with thick pouting lips, black little weasel eyes, and great billowing chops, swellings and furrows of fat which prolonged themselves round to the back of his neck. In the middle of all this riot was a heavy-beaked near-East snout. No less likeable character ever slouched the earth, and even his mother had contracted a strong aversion for him long before he was weaned....1

Mr. Marks, though, is only part of the equation. His butler, Mr Bilker, is the other.

[….] A word about this Mr Bilker. He was an ex-butler, at one time well known to the police. He’d been the inside-contact for some big ‘jobs’ at the expense of his employers. He looked every other inch a butler still, tall, slim, solemn-visaged, inscrutable, super-efficient. His voice was beautifully suave and cultured and every word precisely articulated. The judge, a notorious donator of long sentences, had said he was sorry to see a man of his type standing in the dock. Mr Bilker had replied he was equally sorry to see a judge of His Lordship’s type sitting on the Bench, and received an extra year for impertinence. Nat had found him headwaitering in a night-joint and realised he was just the boy for his purposes. He’d been dead right....

Marks orders a former partner killed, and Mr. Bilker inadvertently incinerates the target alive. The black comedy that ensues owes a lot to Wakefield's great skill using dialogue as action.

In his entry on the Le Fanu in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986), editor Jack Sullivan includes H. Russell Wakefield in a list of "antiquarian followers" of M. R. James. Sullivan lists Wakefield with E. G. Swain and R. H. Malden.

This subclassification is an error. It has done disservice to the scope of Wakefield's accomplishments. The use of old grave inscriptions and artifacts in a story does not qualify a writer to be pigeonholed "in the M. R. James tradition." 2

Early in his career, Wakefield had more in common with E. F. Benson and Oliver Onions, two writers whose contemporary reputations rested on popular comedies, melodramas, and crime books. Unlike them, H. R. Wakefield never made a living from writing after the first few years of his career. But his stories explored similar types of men, women, workplaces, houses, and properties as theirs do, and all three writers clearly worked hard at realistically depicting a modern world shaded with the spectral.3

Sullivan is correct when he lists Wakefield's strengths as a writer, his "cold efficiency" and "masterful combination of romantic Sublimity with modern compression."

And he also spares space to quote E. F. Bleiler on Strangers from Sheol as featuring, along with traditional stories, a "more modern, more complex, partially symbolic story now best written by Aickman."

Sullivan concludes by stating that late Wakefield work registered "a decline in narrative power and spectral atmosphere." This summation can only be true if we assume Wakefield to be correctly retconned into the M. R. James school, rather than as a writer who moved from the world of E. F. Benson and Oliver Onions to the world of Aickman, Matheson, Shirley Jackson, and Gerald Kersh in his lifetime.

* * *

Jay

16 June 2023

[1.] In this he shares something with M. R. James of "The Uncommon Prayer Book" (1925), about which I have written here.

[2] In Unutterable Horror (2005) S. T. Joshi sums up Wakefield's career thus:

[….] Lovecraft enjoyed several stories from his first two collections, but many of them are undistinguished, such as “The Red Lodge,” a routine story of a house haunted as a result of murders committed in the past; “‘He Cometh and He Passeth By,’” a shameless rip-off of M. R. James’s “Casting the Runes” and clearly meant to portray the moral evil of Aleister Crowley; and “The Seventeenth Hole at Duncaster,” in which a wood near a golf course apparently has evil properties, for no ascertainable reason.

Some later tales reveal moments of interest. “A Black Solitude” presents the fascinating conception of the spirits of two evil dead people who have fused into one entity. The protagonist of the story, Apuleius Charlton, appears to be a kind of melding of Crowley and Oscar Wilde. In “The Triumph of Death” we find an effective portrayal of a vicious sadist, one Miss Pendleham, who has driven several companions to death by forcing them to experience hauntings in her house. “A Kink in Space-Time” involves a man who sees his own ghost, but it is somewhat clumsy in execution. “‘Immortal Bird’” is a rather grisly tale of a man who appears to be able to command birds to do his bidding. Some of Wakefield’s later work does exhibit an engaging misanthropy (and, perhaps less appealingly, also misogyny), but overall his work is not nearly as meritorious as his small legion of ardent followers appear to believe.

Joshi is correct about the misanthropy and misogyny, rhetorical routines Wakefield shared with most of his fellow writers.

[3.]Filing Wakefield with the antiquarian school in literature's muniment chest does smack of irony. Wakefield himself classed passionate readers of the UK ghost story as a small-circle equivalent of "ballet maniacs."

Jay

17 June 2023