Readers unfamiliar with "Lot No. 249" may prefer to read these notes only after reading the story.

"Lot No. 249" (1894) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle begins with a statement similar to Lovecraft's minatory opening of "The Call of Cthulhu" (1928):

[....] when we think how narrow and how devious this path of Nature is, how dimly we can trace it, for all our lamps of science, and how from the darkness which girds it round great and terrible possibilities loom ever shadowly upwards, it is a bold and confident man who will put a limit to the strange by-paths into which the human spirit may wander.

From this generalization, Conan Doyle guides us into the rarefied environs of an Oxford college, to a building with “....a corner turret of an exceeding great age.”

[....] under the weight of its years, and the grey, lichen- blotched blocks of stone are bound and knitted together with withes and strands of ivy, as though the old mother had set herself to brace them up against wind and weather….

From this eagle's view of the learning grounds, Conan Doyle strikes a note reminiscent of Gray's Elegy:

[....] From the long-gowned, pedantic scholars of Plantagenet days down to the young bloods of a later age, how full and strong had been that tide of young English life. And what was left now of all those hopes, those strivings, those fiery energies, save here and there in some old-world churchyard a few scratches upon a stone, and perchance a handful of dust in a mouldering coffin?

Conan Doyle has thus swiftly connected several ideas for the reader, principally learning and thanatos, which "Lot No. 249" will quickly commence to dramatize.

Sighting

[....] Sighting clearly signals a release of material that in any psychological reading of Horror is likely to have been repressed, though a wholly expressionist reading of the dynamic between the prior world, and the world Sighting exposes to view, does unduly restrict the range of meanings intended here. It is still surely the case that something like the return of the repressed - the re-emergence into sight of that which “ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light”, as Sigmund Freud describes the uncanny in his famous essay “Das Unheimlich” (1919 Imago 5) - does characterize Sighting…. for Freud the Uncanny is simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar. (Clute, 411)

A May evening in the year 1884.

Compounding preliminaries noted above, (the cautions and the explored locus), Conan Doyle provides a specific warning at the start of the action; scholar athlete Jephro Hastie tells his older friend Abercrombie Smith not to mix with Smith's abominable downstairs neighbor, the fat and devious Edward Bellingham.

When Hastie leaves, Smith resumes studying. Conan Doyle comments suggestively, anticipating Freud, that Smiths’ textbook is

a formidable, green-covered volume, adorned with great, coloured maps of that strange, internal kingdom of which we are the hapless and helpless monarchs.

Then the crisis erupts, at first as a cry from below – Bellingham’s rooms – then as a call for help from Bellingham’s friend, Monkhouse Lee. When Smith goes downstairs to help, he crosses a threshold into a decadent world:

It was such a chamber as he had never seen before—a museum rather than a study. Walls and ceiling were thickly covered with a thousand strange relics from Egypt and the East. Tall, angular figures bearing burdens or weapons stalked in an uncouth frieze round the apartments. Above were bull-headed, stork-headed, cat-headed, owl-headed statues, with viper-crowned, almond-eyed monarchs, and strange, beetle-like deities cut out of the blue Egyptian lapis lazuli. Horus and Isis and Osiris peeped down from every niche and shelf, while across the ceiling a true son of Old Nile, a great, hanging-jawed crocodile, was slung in a double noose.

In the centre of this singular chamber was a large, square table…. in order to make room for a mummy case, which had been conveyed from the wall, as was evident from the gap there, and laid across the front of the table. The mummy itself, a horrid, black, withered thing, like a charred head on a gnarled bush, was lying half out of the case, with its clawlike hand and bony forearm resting upon the table. Propped up against the sarcophagus was an old yellow scroll of papyrus, and in front of it, in a wooden arm-chair, sat the owner of the room, his head thrown back, his widely-opened eyes directed in a horrified stare to the crocodile above him, and his blue, thick lips puffing loudly with every expiration.

Monkhouse Lee is described as a

handsome young fellow, olive-skinned and dark-eyed, of a Spanish rather than of an English type, with a Celtic intensity of manner which contrasted with the Saxon phlegm of Abercrombie Smith.

Once Bellingham is restored, Smith advises: “I think that with your nervous system you should take up some less morbid study.”

Thickening

[....]Thickening begins after the uncanny afflatus of SIGHTING begins to fade, and the future adumbrated in the terrorizing flash of Sighting begins to come true.

[....] the process of Thickening will normally be felt as a cumulative movement towards a further stage: betrayals and mysterious absences (or presences) and keys that do not open and trains that do not come clot the mise en scene, force protagonists down paths they do not wish to tread; nothing adds up; confusion reigns; life is inherently impeded…. (Clute, 417)

Conan Doyle describes two kinds of male friendship in "Lot No. 249."

Smith and Hastie are presented as equals. At the start of "Lot No. 249.”

they had spent their evening upon the river, but apart from their dress no one could look at their hard-cut, alert faces without seeing that they were open-air men—men whose minds and tastes turned naturally to all that was manly and robust.

Smith is the older man, having studied medicine “four years at Glasgow and at Berlin.” He is thus the more cosmopolitan of the pair, for all his phlegm.

If a man could not be measured by a public-school standard, then he was beyond the pale with Hastie. Like so many who are themselves robust, he was apt to confuse the constitution with the character, to ascribe to want of principle what was really a want of circulation.

As "Lot No. 249" proceeds, Smith and Hastie rely on each other as the crisis on campus grows. They do not fail one-another.

Bellingham and Monkhouse Lee have a different kind of relationship. Where Bellingham is gross, Lee is thin and lithe. Lee initially defends Bellingham’s interests.

‘What the deuce can have frightened him so?’ he asked.

‘It’s the mummy.’

‘The mummy? How, then?’

‘I don’t know. It’s beastly and morbid. I wish he would drop it. It’s the second fright he has given me. It was the same last winter. I found him just like this, with that horrid thing in front of him.’

‘What does he want with the mummy, then?’

‘Oh, he’s a crank, you know. It’s his hobby. He knows more about these things than any man in England. But I wish he wouldn’t!

Bellingham is eventually to be Lee's brother-in-law. But over the course of "Lot No. 249" they have a falling out. Lee discovers his sister's future husband is involved in something more than scholarly – and cancels the nuptials.

But even before this, Bellingham seems to be looking for a replacement for Lee. He tells Smith

‘....Lee is a good fellow, an honest fellow, but he is without strength or ambition. He would not make a fit partner for a man with a great enterprise. He would not make a fit partner for me.’

Smith begins to note sounds of walking and talking in Bellingham’s rooms, even when Bellingham is out. Thomas Styles, the scout, attests to this as well, wondering if Bellingham has a secret roommate. Bellingham tells Smith he has a dog.

Bellingham had lied to him, and lied so clumsily that it looked as if he had desperate reasons for concealing the truth. Smith knew that his neighbour had no dog. He knew, also, that the step which he had heard upon the stairs was not the step of an animal. But if it were not, then what could it be? There was old Styles’s statement about the something which used to pace the room at times when the owner was absent. Could it be a woman? Smith rather inclined to the view. If so, it would mean disgrace and expulsion to Bellingham if it were discovered by the authorities, so that his anxiety and falsehoods might be accounted for. And yet it was inconceivable that an undergraduate could keep a woman in his rooms without being instantly detected. Be the explanation what it might, there was something ugly about it, and Smith determined, as he turned to his books, to discourage all further attempts at intimacy on the part of his soft-spoken and ill-favoured neighbour.

But this mystery is forgotten when a fellow student, Long Norton, is assaulted and nearly strangled to death.

‘....Norton swears that it was not human, and, indeed, from the scratches on his throat, I should be inclined to agree with him.’

‘What, then? Have we come down to spooks?’

Shortly after this, Monkhouse Lee implores Smith to move out of his rooms and away from Bellingham. Smith refuses, but will shortly learn better.

Revel

[....] Revel…. marks the moment when a horror tale ceases to describe the welling up of the repressed and the subversive within the restraining walls of “civilization”, and begins to tell it as it is…. Revel tends to announce the world to come (and the season it is analogous to is fall). The wings of revelation create a wind from the future, from the winter of the world that the occupants of the early 21st century are now entering…. Revel is the action of the real world announcing itself. It is “Reason” awakening itself from sleep. (Clute, 421)

The rising tempo of carnivalesque horrors begins to accelerate two-thirds of the way into "Lot No. 249."

Smith, returning a book to Bellingham, finds his neighbor out and the door unlocked. As he leaves the book, he notes that the mummy’s sarcophagus is empty.

As he leaves Bellingham's rooms

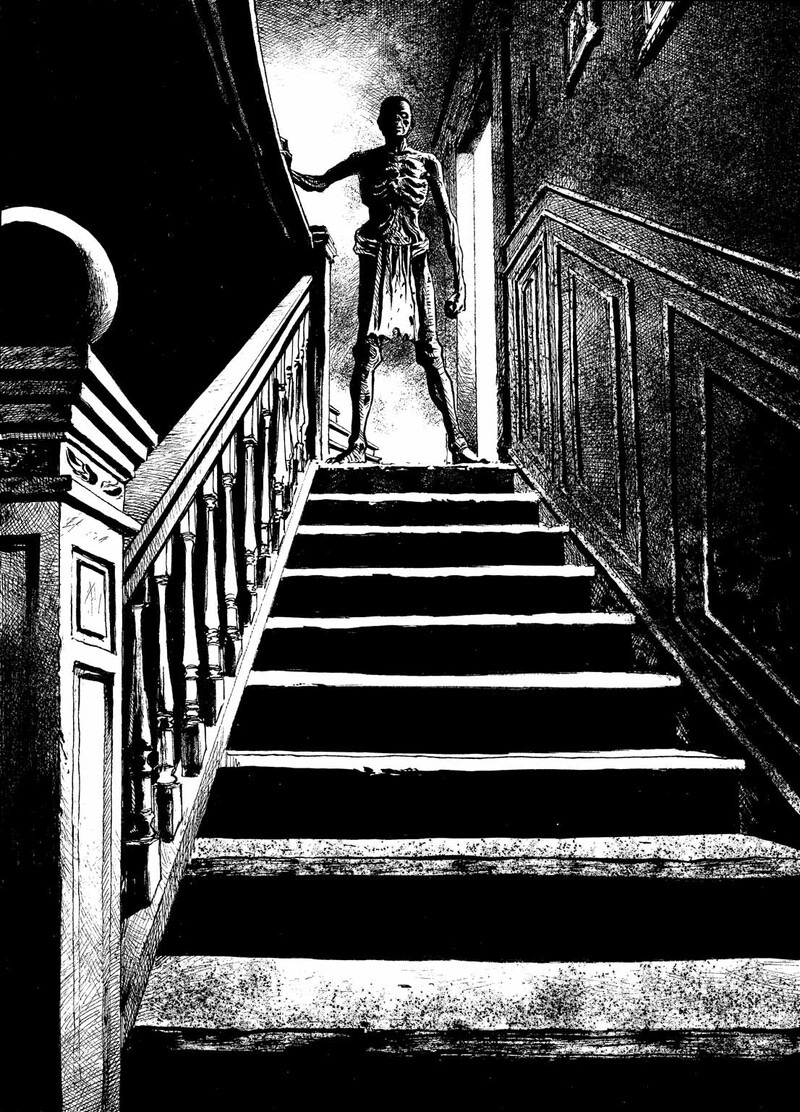

The spiral stair was as black as pitch, and Smith was slowly making his way down its irregular steps, when he was suddenly conscious that something had passed him in the darkness. There was a faint sound, a whiff of air, a light brushing past his elbow, but so slight that he could scarcely be certain of it. He stopped and listened, but the wind was rustling among the ivy outside, and he could hear nothing else.

‘Is that you, Styles?’ he shouted.

There was no answer, and all was still behind him. It must have been a sudden gust of air, for there were crannies and cracks in the old turret. And yet he could almost have sworn that he heard a footfall by his very side.

He had emerged into the quadrangle, still turning the matter over in his head, when a man came running swiftly across the smooth- cropped lawn.

‘Is that you, Smith?’

‘Hullo, Hastie!’

‘For God’s sake come at once! Young Lee is drowned! Here’s Harrington of King’s with the news. The doctor is out. You’ll do, but come along at once. There may be life in him.’

‘Have you brandy?’

‘No.’

‘I’ll bring some. There’s a flask on my table.’

Smith bounded up the stairs, taking three at a time, seized the flask, and was rushing down with it, when, as he passed Bellingham’s room, his eyes fell upon something which left him gasping and staring upon the landing. The door, which he had closed behind him, was now open, and right in front of him, with the lamp- light shining upon it, was the mummy case. Three minutes ago it had been empty.

After they have revived him, his friends commiserate with Monkhouse Lee for falling into the river.

‘I was thrown in. I was standing by the bank, and something from behind picked me up like a feather and hurled me in. I heard nothing, and I saw nothing. But I know what it was, for all that.’

‘And so do I,’ whispered Smith.

Lee looked up with a quick glance of surprise. ‘You’ve learned, then?’ he said. ‘You remember the advice I gave you?’

‘Yes, and I begin to think that I shall take it.’‘

All this settled in his thoughts, together with the many little incidents which had previously turned him against his neighbour, and the singular circumstances under which he was first called in to him. What had been a dim suspicion, a vague, fantastic conjecture, had suddenly taken form, and stood out in his mind as a grim fact, a thing not to be denied.

Smith returns to the tower to confront Bellingham.

[....] the man himself looked out at him. With his fat, evil face he was like some bloated spider fresh from the weaving of his poisonous web…. but there was the gleam of a hidden laugh in his eyes….

‘I tell you what it is, Master B., they have given up burning folk like you, but we still keep a hangman, and, by George! if any man in this college meets his death while you are here, I’ll have you up, and if you don’t swing for it, it won’t be my fault. You’ll find that your filthy Egyptian tricks won’t answer in England.’

‘You’re a raving lunatic,’ said Bellingham.

‘All right. You just remember what I say, for you’ll find that I’ll be better than my word.’

The door slammed, and Smith went fuming up to his chamber, where he locked the door upon the inside, and spent half the night in smoking his old briar and brooding over the strange events of the evening.

The next evening, Smith takes a walk to visit a friend of his older brother, Reverend Plumptree Peterson, who lives outside Oxford. This calamitous walk is the high point of "Lot No. 249," and of Conan Doyle's horror stories, in evoking horrified affect.

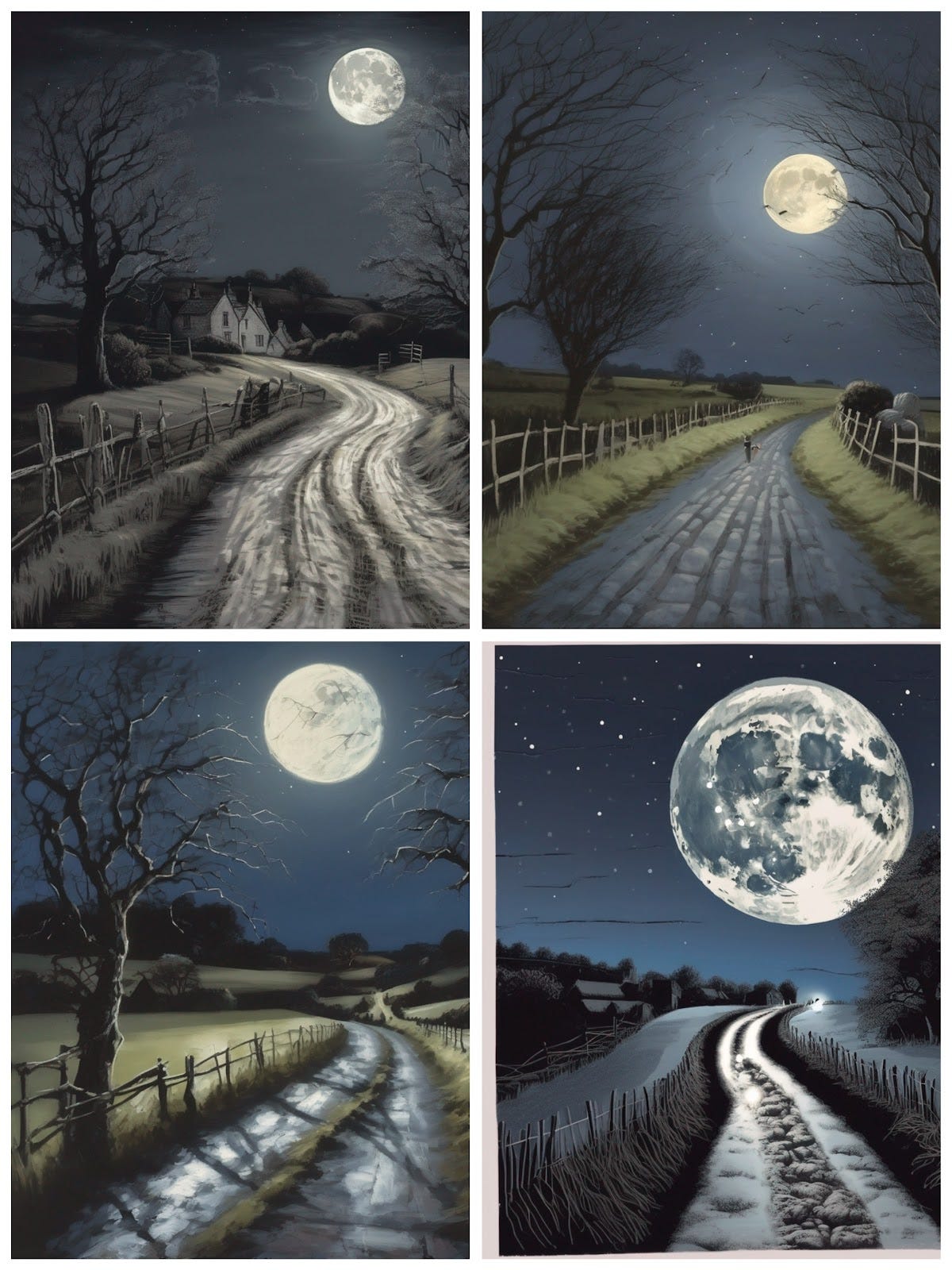

[....]The half-moon lay in the west between two Gothic pinnacles, and threw upon the silvered street a dark tracery from the stone-work above. There was a brisk breeze, and light, fleecy clouds drifted swiftly across the sky. Old’s was on the very border of the town, and in five minutes Smith found himself beyond the houses and between the hedges of a May-scented Oxfordshire lane.

It was a lonely and little frequented road which led to his friend’s house. Early as it was, Smith did not meet a single soul upon his way. He walked briskly along until he came to the avenue gate, which opened into the long gravel drive leading up to Farlingford. In front of him he could see the cosy red light of the windows glimmering through the foliage. He stood with his hand upon the iron latch of the swinging gate, and he glanced back at the road along which he had come. Something was coming swiftly down it.

It moved in the shadow of the hedge, silently and furtively, a dark, crouching figure, dimly visible against the black background. Even as he gazed back at it, it had lessened its distance by twenty paces, and was fast closing upon him. Out of the darkness he had a glimpse of a scraggy neck, and of two eyes that will ever haunt him in his dreams. He turned, and with a cry of terror he ran for his life up the avenue. There were the red lights, the signals of safety, almost within a stone’s-throw of him. He was a famous runner, but never had he run as he ran that night.

The heavy gate had swung into place behind him, but he heard it dash open again before his pursuer. As he rushed madly and wildly through the night, he could hear a swift, dry patter behind him, and could see, as he threw back a glance, that this horror was bounding like a tiger at his heels, with blazing eyes and one stringy arm out-thrown. Thank God, the door was ajar….

Reverend Peterson listens to Smith's account of the chase, which Smith confesses has “unmanned” him. He also details everything he has found out about Bellingham. After this, he writes it down and has Peterson witness it.

The next day, at gunpoint, he gives Bellingham a final ultimatum: break up and burn the mummy, herbs, and papyrus that created the crisis. Bellingham, after much attempted bargaining and pleading, complies.

Aftermath

[....] the passage out of Revel - out of the moment of transvaluation of all values into a fixated awareness that the world so exposed is in fact the real world - may be so swift, and the ending of the tale may come so soon, that the desiccating torpor of Aftermath may be no more than glimpsed, a surreal echo of the flash of Sighting which has earlier announced that the end is nigh. This is almost inevitable. The central sense conveyed by Aftermath, after all, is that there is nothing to be done, that there is no cure to hand, no more story to tell, no deus ex machina, no statement that It Was All a Dream….

[....] the central extra-textual or para-textual function of Aftermath, beyond its central role in terminating the story at hand: to flash-freeze the future is the final gift of Horror. (Clute, 348)

Abercrombie Smith's final warning to Bellingham:

‘Now, Master B.,’ said he, ‘I think I have pretty well drawn your teeth. You’ll hear from me again, if you return to your old tricks. And now good-morning, for I must go back to my studies.’

Conan Doyle adds a final paragraph, telling the reader that Bellingham fled to Sudan after Smith's warning, and that

the wisdom of men is small, and the ways of nature are strange, and who shall put a bound to the dark things which may be found by those who seek for them?

This directly echoes the opening of "Lot No. 249":

when we think how narrow and how devious this path of Nature is, how dimly we can trace it, for all our lamps of science, and how from the darkness which girds it round great and terrible possibilities loom ever shadowly upwards, it is a bold and confident man who will put a limit to the strange by-paths into which the human spirit may wander.

It is a lovely narrative boomerang touch, providing symmetry in the teeth of action and the terminal recessional mood.

Noted

✂249 is not the only number that recurs in "Lot No. 249." Both Smith and Hastie take the stairs three at a time.

✂In his cottage, Monkhouse Lee has a few oleographs on the wall, a far cry from Bellingham's richly appointed rooms. In the twentieth century, the prefix oleo was also a synonym for margarine: “fake” butter. Disinterred mummies might be called fake creatures, uncanny puppets, or simply inauthentic. Oleograph art work on one's wall announced the owner is a parvenue. Perhaps Monkhouse Lee's roommate contributed them?

✂Fat and evil Bellingham seems a premonition of actual “unnatural” historical figures well-known in the fin de siecle: Oscar Wilde and Alesiter Crowly. In 1892, the year "Lot No. 249" was published, Wilde was still on the heights, but had already become involved with Douglas. Wisely, Monkhouse Lee refused the final step of becoming Bellingham's “Bosie.”

Critical responses

E. F. Bleiler, jocularly:

Bellingham, a rather unpleasant man, has discovered the secret of reanimating Egyptian mummies. One of his experiments, Lot No. 249, is terrorizing the neighborhood. The animating process is magical and involves a remarkable papyrus. The spoil-sport protagonist makes Bellingham destroy everything. (Bleiler 169)

Matt Cardin:

[....] one of the curiosities of [Conan Doyle's mummy] stories is that in each the actions are motivated and driven by a frustrated sexuality. In “The Ring of Thoth,” this sexuality culminates in a barely concealed act of necrophilia, for though (as we later learn) Sosra has endured for nearly 3,500 years, he has been unable to find another woman or experience a love comparable to that he found with Atma. In his unwrapping of Atma’s remarkably well-preserved corpse, a strong death eroticism is established, with the mummy possessing “long, black, glossy tresses . . . a low, white forehead, with a pair of bright, deeply fringed eyes, and a straight, well-cut nose . . . [and] a sweet, full, sensitive mouth, and a beautifully curved chin,” and it culminates after Sosra, “hurling himself down upon the ground beside the mummy, he threw his arms around her, and kissed her repeatedly upon the lips and brow.” The sexualities depicted in “Lot No. 249” are less explicit and transgressive, but a creepy sexuality is nevertheless present, first in the descriptions of Bellingham, described by Hastie as fat and somehow innately perverse: “My gorge always rises at him. I should have put him down as a man with secret vices—an evil liver.” Nevertheless, despite these hints of shady sexuality, Bellingham has managed to become engaged to Eveline Lee, sister of fellow-student Monkhouse Lee, which greatly disgusts Hastie, who refers to them as “a toad and a dove, that’s what they always remind me.” However, this relationship does not last, for Lee discovers Bellingham’s secret and breaks the engagement, thus precipitating Bellingham’s using the mummy in his attacks on those who thwarted him…. (Cardin 129)

[....] No specific literary model can be established for “Lot No. 249,” and Doyle carefully refrains from giving too manydetails lest he be held accountable for misstatement of error: even the mummy is nameless, reduced to an auctioneer’s lot. (Cardin 130)

Cardin’s discussion of Bellingham’s engagement to Monkhouse Lee's sister leaves unsaid Bellingham's relationship to Lee himself, and his effort to recruit a stronger partner, whom he thinks he's found in Abercrombie Smith.

* * *

Jay

6 January 2024

(Luckhurst 276)

Bleiler, Everett Franklin. The Guide to Supernatural Fiction. 1983.

Clute, John. Stay. Hachette UK, 2016

Conan Doyle, Arthur. “Lot No. 249”. Penguin 2016.

Cardin, Matt. Mummies Around the World: An Encyclopedia of Mummies in History, Religion, and Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO, 2014.

Luckhurst, Roger. The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy. Oxford UP, 2012.