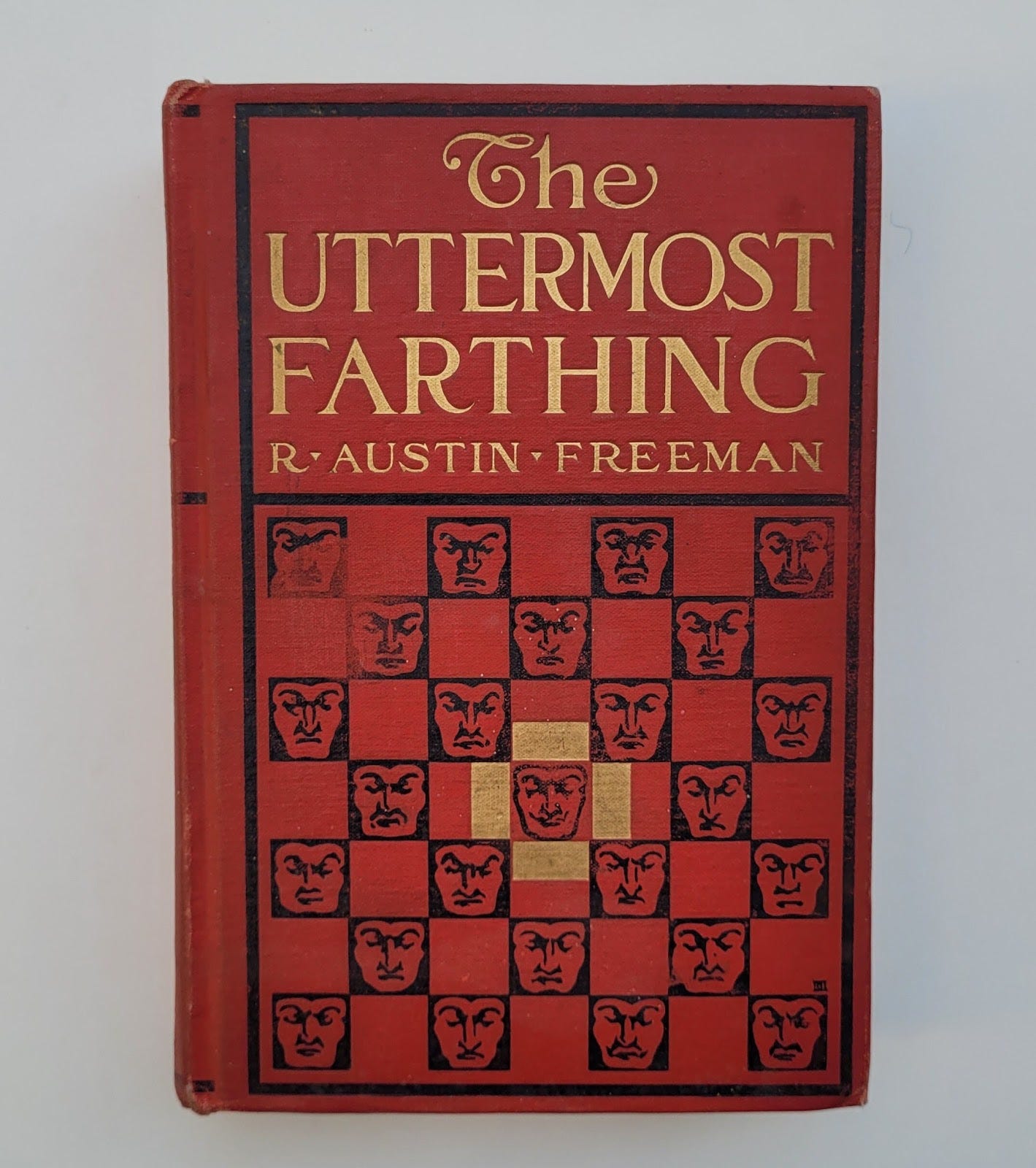

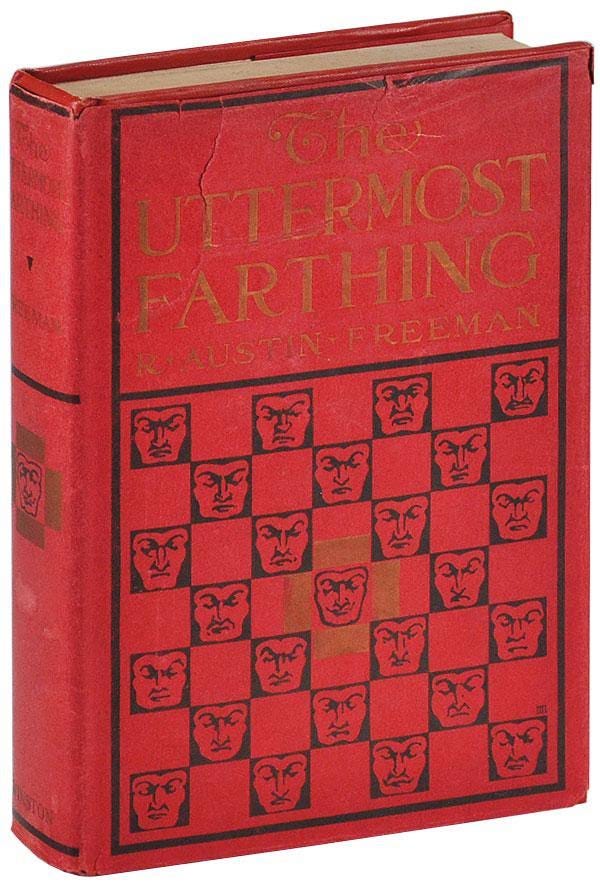

Murder for revenge: The Uttermost Farthing (1914) by R. Austin Freeman

Uncanny moments as a gifted forensic anthropologist spends twenty years tracking-down his wife's killer...

Those unfamiliar with The Uttermost Farthing may prefer to read these notes only after reading the novel.

The Uttermost Farthing is a crime novel worth seeking-out. It is widely and freely available online, and rewards reading. Austin Freeman is known for his series characters, but none appear in The Uttermost Farthing.

Parenthetically, the novel dramatizes the ideas of the period's eugenicists, creating a few surprising moments for today's politically correct reader. Austin Freeman's craft is on full display as he carefully braids the melodramas of eugenic sociology and personal vendetta.

* * *

The novel begins with a chapter narrated by protagonist Humphrey Challoner's friend Wharton. Challoner conducts him on what turns out to be a final tour of his personal museum.

We are alerted early in the tour to pay close attention:

....This collection I could never quite understand. It consisted chiefly of human and other mammalian skeletons, all of which presented certain small deviations from the normal; but its object I could never make out —until after his death; and then, indeed, the revelation was a truly astounding one.

He escorts Wharton to a secret recess. And here we have the first of two uncanny moments that open and close the story:

"That row of books you will take possession of and examine when my lease falls in. You are my executor and this collection will be yours to keep or give away or destroy, as you think fit. The books consist of a finger-print album, a portrait album, a catalogue and a history of the collection. You will find them all quite interesting. Now I will show you the gems if you will lift those boxes down on to the table."

I did as he asked; lifting down the pile of shallow boxes and placing them, at his direction, side by side on the table. When they were arranged to his satisfaction, he took off the lids with somewhat of a flourish, and I uttered an exclamation of amazement.

The boxes were filled with dolls' heads; at least, such I took them to be. But such dolls! I had never seen anything like them before. So horribly realistic and yet so unnatural! I can only describe the impression they produced by that much-misused word "weird." They were uncanny in the extreme, suggesting to the beholder the severed heads of a company of fantastic, grotesque-looking dwarfs. Let me try to describe them in detail.

Each head was about the size of a small monkey's, that is, about four inches long. It appeared to be made of some fine leather or vellum, remarkably like human skin in texture. The hair in all of them was disproportionately long and very thick, so that it looked somewhat like a paint-brush. But it was undoubtedly human hair. The eyebrows too were unnaturally thick and long and so were the mustache and beard, when present; being composed, as I could plainly see, of genuine mustache and beard hairs of full length and very closely set. Some were made to represent clean-shaven men, and some even showed two or three days' growth of stubble; which stubble was disproportionately long and most unnaturally dense. The eyes of all were closed and the eyelashes formed a thick, projecting brush. But despite the abnormal treatment of the hairy parts, these little heads had the most astonishingly realistic appearance and were, as I have said, excessively weird and rather dreadful in aspect. And, in spite of the closed eyes and set features, each had an expression and character of its own; each, in fact, seemed to be a faithful and spirited portrait of a definite individual. They were upwards of twenty in number, all male and all represented persons of the European type. Each reposed in a little velvet-lined compartment and each was distinguished by a label bearing a number and a date.

I looked up at Challoner and found him regarding me with an inscrutable and hideous smile.

"These are very extraordinary productions, Challoner," said I. "What are they? And what are they made of?"

"Made of, my dear fellow?" said he. "Why, the same as you and I are made of, to be sure."

"Do you mean to say," I exclaimed, "that these little heads are made of human skin?"

"Undoubtedly. Human skin and human hair. What else did you think?"

I looked at him with a puzzled frown and finally said that I did not understand what he meant....

The modern reader of crime novels will have no trouble figuring out what the dying Challoner insinuates.

* * *

Challoner begins the hunt for his wife's killer by setting a trap in his own house. This leads to some comedy preceding a trio of killings. Readers who enjoy scenes of fastidious preparation (traps on basement steps, lethal homemade "concussor" weapons, Yale locks) will find much to appreciate in the second and third chapters.

Wharton is left to interject about Challoner's program: "Was it a rational outlook or that of a lunatic?" Challoner himself remarks that as the first criminal enters the trap, his own personality changes.

....I watched him and meanwhile debated whether or not I should take the opportunity to knock him down. That was undoubtedly the proper course. But I could not bring myself to do it. A spirit of wild mischief possessed me; a strange, unnatural buoyancy and fierce playfulness that impelled me to play insane, fantastic tricks. It was a singular phenomenon. I seemed suddenly to have made the acquaintance of a hitherto unknown moiety of a dual personality.

It's the same pleasure at toying with the "player on the other side" that readers of novels by later writers like Buchan, Sapper, and Dornford Yates will recognize.

* * *

Challoner realizes that his initial tactic for luring his wife's killer back to the same house will not work. He goes back to clues the thief left at the crime scene: fingerprints and hair samples.

"The result was a most startling discovery. It was ringed hair. The gray appearance was due, not to the usual mingling of white and dark hairs, but to the fact that each separate hair was marked by alternate rings of black and white. Now, variegated hairs are common enough in the lower animals which have a pattern on the fur. The tabby cat furnishes a familiar example. But in man the condition is infinitely rare; whence it was obvious that, with these hairs and the finger-prints, I had the means of infallible identification. But identification involves possession of the person to be identified. There was the difficulty. How was it to be overcome?

Challoner embarks on a career as a barber. He sets up shop at the crossroads of London crime: Whitechapel.

If I could not entice the criminal population into my domain, how would it be to reconnoiter theirs? The alien area of London was well known to me, for it had always seemed interesting since my visit to Warsaw, and, judging from the police reports, it appeared to be a veritable happy hunting-ground for the connoisseur in criminals.

"My preparations for the new activities on which I was to enter were quickly made. In my Bloomsbury house I installed as caretaker a retired sergeant-major of incomparable taciturnity. I locked up the museum wing and kept the keys. I took a few lessons in haircutting from a West-End barber. I paid my advance rent , sent in a set of bedroom furniture to my new premises in Saul Street, Whitechapel, abandoned the habit of shaving for some ten days, and then took possession of the shop.

"At first the customers were few and far between. A stray coster or carman came in from time to time, but mostly the shop was silent and desolate. But this did not distress me. I had various preparations to make and a plan of campaign to settle. There were the cellar stairs, for instance; a steep flight of stone steps, unguarded by baluster or handrail. They were very dangerous. But when I had fitted a sort of giant stride by suspending a stout rope from the ceiling, I was able to swing myself down the whole flight in perfect safety. Other preparations consisted in the placing, of an iron safe in the parlor (with a small mirror above it) and the purchase of a tin of stiff cart-grease and a few large barrels. These latter I bought from a cooper in the form of staves and hoops, and built them up in the cellar in my rather extensive spare time...."

* * *

One winter day, after a hectic succession of barbering customers, Challoner receives a thunderbolt.

"I raised my eyes and they fell on my reflection in the large mirror; and suddenly it was borne in on me that I was an old man. The passing years of labor and mental unrest had left deep traces. My hair, which was black when I first came to the east, was now snow-white and the face beneath it was worn and wrinkled and aged. The sands of my life were running out apace. Soon the last grains would trickle out of the glass; and then would come the end—the futile end, with the task still unaccomplished. And for this I had dragged out these twenty weary years, ever longing for repose and the eternal reunion! How much better to have spent those years in the peace of the tomb by the dear companion of my sunny hours!

"I stepped up to the glass to look more closely at my face, to mark the crow's-feet and intersecting wrinkles in the shrunken skin. Yes, it was an old, old face; a weary face, too, that spoke of sorrow and anxious thought and strenuous, unsatisfying effort. And presently it would be a dead face, calm and peaceful enough then; and the wretch who had wrought all the havoc would still stalk abroad with his heavy debt unpaid.

"Something on the surface of the mirror interposed between my eye and the reflection, slightly blurring the image. I focussed on it with some difficulty and then saw that it was a group of finger-marks; the prints made by the greasy fingers of my dandy customer when he had leaned on the glass to inspect his teeth. As they grew distinct to my vision, I was aware of a curious sense of familiarity; at first merely subconscious and not strongly attracting my attention. But this state lasted only for a few brief moments. Then the vague feeling burst into full recognition. I snatched out my lens and brought it to bear on those astounding impressions. My heart thumped furiously. A feeling of awe, of triumph, of fierce joy and fiercer rage surged through me, and mingled with profound self-contempt.

"There could be no mistake. I had looked at those finger-prints too often. Every ridge-mark, every loop and whorl of the varying patterns was engraved on my memory. For twenty years I had carried the slightly enlarged photographs in my pocket-book, and hardly a day had passed without my taking them out to con them afresh. I had them in my pocket now to justify rather than aid my memory.

"I held the open book before the glass and compared the photographs with the clearly-printed impressions. There were seven finger-prints on the mirror; four on the right hand and three on the left, and all were identical with the corresponding prints in the photographs. No doubt was possible. But if it had been—

"I darted across to the chair. The floor was still littered with the cuttings from that villain's head. In my idiotic preoccupation with the other man I had let that wretch depart without a glance at his hair. I grabbed up a tuft from the floor and gazed at it. Even to the unaided eye it had an unusual quality when looked at closely; a soft, shimmering appearance like that of some delicate textile. But I gave it only a single glance. Then rushing through to the parlor, I spread a few hairs on a glass slip and placed it on the stage of the microscope.

"A single glance clenched the matter. As I put my eye to the instrument, there, straying across the circular field, were the broad gray stripes, each with its dark line of medulla obscured at intervals by rings of tiny bubbles. The demonstration was conclusive. This was the very man. Humanly speaking, no error or fallacy was possible...."

The killer, dandy, and thief is named Piragoff. Challoner must wait half a year for him to return for another haircut and shave. When he does, Challoner quickly baits the trap: enticing Piragoff to assist in robbing his house and museum.

"I was, on the whole, very well pleased with the arrangement. Particularly pleased was I with Piragoff's transparent plan for disposing of me. For, now that it really came to action, I found myself shying somewhat at the office of executioner; though I meant to do my duty all the same. But the fact that this man was already arranging coolly to murder me made my task less unpalatable. The British sporting instinct is incurable.

"Piragoff's scheme was perfectly simple. We should go together to the house, we should bring away the spoil—I carrying half—convey it to my premises in Saul Street early on Sunday morning. Then we should break up the 'stuff,' and when our labors were concluded, and I was of no further use, he would knock me on the head. The quiet back gate would enable him to carry away the booty in instalments to his lodgings. Then he would lock the gate and vanish. In a few days the police would break into my house and find my body; and Mr. Piragoff, in his hotel at, say Amsterdam, would read an account of the inquest. It was delightfully simple and effective, but it failed to take into account the player on the opposite side of the board...."

Challoner has become an old man while perfecting his role as a Whitechapel barber. Indeed, it is worth noting that Challoner spends more of his life barbering than he ever did as doctor or husband. His obvious competence and success in this socially useful work, however, strikes Challoner as a species of living death.

* * *

Lording the situation over Piragoff is done subtly once they are in the museum several nights later.

"I piloted him through to the museum and switched on a single electric lamp which filled the great room with a ghostly twilight. Piragoff looked about him inquisitively and his eye fell on the long wall-case with the dimly-seen, pallid shapes of the company within it. His face blanched suddenly and he stared with wide-open eyes.

"'God!' he exclaimed, 'what are those things?'

"'Those skeletons?' said I. 'They are part of the collection. The fellow who owns this place hoards all sorts of trash. Come round and have a look at them.'

"'But skeletons!' he whispered. 'Skeletons of men! Ah, I do not like them!'

"Nevertheless he followed me round the room, peering in nervously at the case of skulls as we passed. I walked him slowly past the whole length of the wall-case and he stared in at the twenty-four motionless, white figures, shuddering audibly. I must admit that their appearance was very striking in that feeble light; their poses were so easy and natural and their faces, modeled by broad shadows, so singularly expressive. I was very pleased with the effect....

"' But they are horrible!' gasped Piragoff. 'They seem to be alive. They seem to beckon to one—to say, "Come in here: come in and stay with us." Ah! they are dreadful! Let us go away from them.'

Challoner guides Piragoff to the shadow boxes with their uncanny contents. Piragoff is uniquely placed to appreciate the surprise.

"'There is nothing there but books and those boxes. Lift the boxes down, pig, and let us see what is in them.'

"I lifted the boxes from the shelf.

"'They are very light,' I said. 'And here are two pistols on top of them.'

"These pistols were the surprise that I had prepared in a spirit of mischief. I had taken them from the pockets of the last two specimens and kept them for the sake of the devices that those two imbeciles had scratched on the butts.

"'Pistols!' exclaimed Piragoff. 'Let me look at them.' He snatched the weapons from the top of the box and took them over to the lamp. Immediately I heard a gasp of astonishment.

"'God! But this is a strange thing! Here is Louis Plotcovitch's pistol! And this other belonged to Boris Slobodinsky! They have been here too!'

"He stared at me open-mouthed, holding the pistols—which I had carefully unloaded—one in each trembling hand. What little nerve he had had was going fast.

"I laid the boxes on a small table and switched on the lamp that hung close over it. High up above the table was one of the cross-beams of the roof. From the beam there hung down two purchase-tackles. The tail-rope of each tackle ended in a noose that was hitched on a hook on the wall, and the falls of the two tackles were hitched lightly over two other hooks. But none of these appliances was visible. The shaded lamp threw its bright light on the table only.

"Piragoff came across the room and laid down the pistols.

"'Open those boxes,' he said gruffly, 'and let us see what is in them.'

"I took off the lid of one; and Piragoff started back with a gasp, but came back, snuffing at the box like a frightened animal.

"'What the devil are these things?' he demanded in a hoarse whisper.

"'They look like dolls' heads,' I answered.

"'They look like dead men's heads,' he whispered, shudderingly, 'only they are too small. They are dreadful. This collector man is a devil. I should like to kill him.' He glared with horrid fascination at the little dry preparations—there were eight in this box, each in its own little black velvet compartment with its number and date on the label. I opened the second box—also containing eight—and he stared into that with the same shuddering fascination.

"'What do you suppose these dates mean?' he whispered.

"'I suppose,' I replied, 'those are the dates on which he acquired them. Here is another box.' This, the last one, was intended to hold nine heads, but it contained only eight—at present. There was an empty compartment of red velvet in the middle, on either side of which were the heads of the last two specimens, twenty-three and twenty-four.

"I took off the lid and stood back to see what would happen.

"Piragoff stared into the box without speaking for two or three seconds. Suddenly he uttered a shriek. 'It is Boris! Boris and Louis Plotcovitch!'

"His figure stiffened. He stood rigid with his hands on his thighs, leaning over the box, his hair bristling, his white face running with sweat, his jaw dropped; the very personification of horror. And of a sudden he began to tremble violently.

"I looked at him with disgust and an instantaneous revulsion of feeling. What! Should I call in the aid of all those elaborate appliances to dispatch a poor trembling devil like this? I would have none of them. The concussor was good enough for him. Nay, it was too good.

"I reached out behind me and lifted one of the nooses from its hook. Its own weight had nearly closed the loop, for the steel eyelet spliced into the end ran very easily and smoothly on the well-greased rope. I opened the loop wide, and leaning towards Piragoff from behind, quietly dropped it over his shoulders, pulling it tight as it fell to the level of his elbows. He sprang up, but at that instant I kicked away one of his feet and pushed him to the unsupported side, when he fell sprawling face downwards. I gave another tug at the rope, and, as he struggled to get to his feet, I snatched the fall of the tackle from its hook and ran away with it, hauling as I went. Looking back, I saw Piragoff slowly rise to the pull of the tackle until he was upright with his feet just touching the floor. Then I belayed the fall securely to one of a pair of cleats, and approached him.

"Hitherto, sheer amazement had kept him silent, but as I drew near him he gave a yell of terror. This would not do. Taking the gag from the place where I had hidden it in readiness, I came behind him and slipped it over his mouth where I secured it, cautiously evading his attempts to clutch at me. It was a poor gag—having no tongue-piece—but it answered its purpose, for it reduced his shouts to mere muffled bellowings, inaudible outside.

"Now that the poor wretch was pinioned and gagged and helpless, my feelings urged me to get the business over quickly. But certain formalities had to be observed. It was an execution. I stepped in front of the prisoner and addressed him.

"'Listen to me, Piragoff.' At the sound of his name he stopped bellowing and stared at me, and I continued, 'Twenty years ago a burglar came to this house. He was in the dining-room at two o'clock in the morning preparing to steal the plate. A lady came into the room and disturbed him. He tried to prevent her from ringing the bell. But she rang it; and he shot her dead. I need not tell you, Piragoff, who that burglar was. But I will tell you who I am. I am the husband of that lady. I have been looking for you for twenty years, and now I have caught you; and you have got to pay the penalty of that murder.'

* * *

Challoner lives out the remaining months of his life back at home. He has spent two decades on the vendetta. He has killed twenty-four men while hunting the twenty-fifth, Piragoff. He has articulated and displayed twenty-five human skeletons, and shrunk twenty-five human heads. He has killed by hand, often in cold blood.

Revenge admits no half-measures.

Jay

26 May 2023