I underlined the following passages between 7 and 10 May of this year. I was in the process of reading a series of books by Jameson.

I enjoyed working on the diagrams, though I never got very far, alas.

* * *

[....] getting out of binary oppositions may often mean, not so much doing away with them, as multiplying them and using the initial ideological starting point as the beginning of a more complicated construction which is at the same time a more complex diagnosis.

[....] and that is the traditional opposition that relates form to content.

[....] the opposition between form and content is only to be overcome (that is to say, made productive) by complicating it, and not by doing away with one of its terms.

[....] form and content finally meet in some new kind of synthesis (which is of course none other than the work of art itself)

[....] holding to a dual perspective for each of our binary terms that we may well find a more satisfactory answer, and that dual perspective may well look like not one, but a series of partial syntheses.

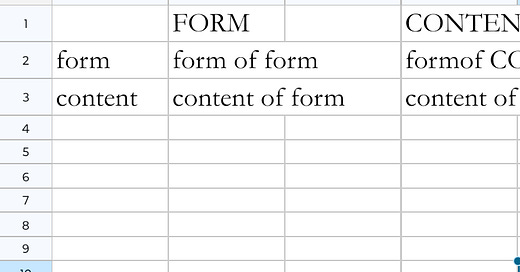

[....] seeing the binary opposition between form and content as a four-term set of positions rather than a simple dualism, and I borrow an oversimplified and vulgarized model for these possibilities from Hjelmslev’s linguistics, which alongside the purer versions of a form-oriented perspective (“the form of the form”) and a content-oriented one (“the content of the content”) adds in two new ones, which result from taking the point of view of each on the realities under consideration.

[....] new terms he designated as the “content of the form” and the “form of the content” respectively, and once our stereotypical views of form and content have been sufficiently startled and rebuked, if not challenged, by the addition of the new entities, we will be in a better position to evaluate the possibilities this ancient dualism still has to offer.

[....] We can make the possibilities visible by seeing both form and content—the horizontal phenomena—from the perspectives of the same categories, now operating as vertical designators respectively: form content CONTENT form of content content of content FORM form of form content of form

[....] each of these combinations or perspectives will project a type of literary criticism that has its own validity as well as its own internal limitations; while at some outside boundary, slipping from description into prescription, each will seem to posit a specific aesthetic and a program for writers to follow.

[My outline for a diagram – JR]

[....] the works have to come first.

[....] We cannot do without projections of the future in practical political life, but we do not have to prognosticate the future of art, something art always does for itself in a twofold way: first, by way of the artist’s own laboratory of forms in which the latter are tested for their continuing productivity; and then by way of the personal taste and aesthetic inclinations and intuitions with which our own historical experience endows us as connoisseurs and consumers.

[....] texts under consideration here owe their existence to conditions and situations of modernism that are no longer ours today.

[....] fourfold possibilities with which any presupposition of the terminology of form and content seems to provide us, I will try briefly to characterize the most familiar results of each.

[....] content of content is inevitably a referential operation, in which we attempt to identify the social and historical realities in which the text comes into being and which it presumably designates.

[....] text comes into being in some kind of real world, and also that its language, however fictional the project, has to manipulate a period language assumed to have its own referentiality.

[....] the content of content—does not yet have a form or in other words is by definition inexpressible and unfigurable.

[....] experienced immediately, that is to say, without the mediation of the various representational and figural systems. But that stage would have to remain purely hypothetical, since we have no way of thinking or theorizing it.

[....] No one has ever seen a social class or experienced one immediately: social classes meanwhile define themselves only in moments of great social crisis and intensity.

[....] the form of the content can be said to encompass everything called ideology in the most comprehensive acceptation of the word.

[....] In literature, the things-in-themselves are the social and historical realities, but also the inner psychic realities, with which the literary text tries desperately to come to terms; the ideologies constitute that enlarged set of categories that necessarily process and organize the intensities of that formless content and seek to produce representations of it.

[....] in literary criticism, as well, we cannot do without these two initial moments of the form–content position, and must always acknowledge the claims these first two perspectives inevitably have on us

[....] whether something new and different is not to be achieved by an unparalleled new effort to silence the voices of ideology altogether, by isolating the pure forms of their representations and substituting the play of those formal categories for an older or now traditional representation of content.

[....] form on itself, of a formalistic production of form; and also into the historical moment designated as modernism, in which the ideological forms of an older content are somehow neutralized and bracketed by an abstraction that seeks to retain only from them their purely formal structures, now deployed in a kind of autonomy.

[....] the pure forms still bear the traces and the marks of the content they sought to extinguish, we find that we have already entered the fourth of our perspectives, that of the content of the form itself.

[....] each of the three preceding moments constitutes a certain kind of perspective itself dialectically presupposes this fourth one, from which their insufficiencies could alone be registered.

[....] this whole form–content issue is neither a purely local, aesthetic problem, nor an equally local and technical philosophical one, but arises over and over again in a variety of contemporary contexts.

[....] formalism was always the professional deformation of academics and intellectuals, inasmuch as the truly bourgeois and middle-class reply to any aesthetic of content was always one of humanism and meaning

[....] evocation of content in this situation always stands for a Brechtian estrangement-effect, a defamiliarization that asks us to imagine what a real political proposal or program, one that had real content, might be.

[....] the problem of content and form largely transcend their merely aesthetic reference and in the long run come to haunt all the corners and closets of the social itself. Indeed, was not communism itself an attempt to endow a purely formalistic and Kantian Second International socialism with genuine content?

[....] This strange new—historically new—feeling or affective tone of late capitalism may now be seen as something like a return of the “sublime” in the sense in which Edmund Burke first perceived and theorized it at the dawn of capital. Like the “sublime” (and “anxiety”), the exhilaration of which we are speaking is not exactly an emotion or a feeling, not a way of living an object, but rather somehow detached from its contents—something like a disposition of the subject which takes a particular object as a mere occasion: this is the sense in which the Deleuze-Guattari account of the emergence, the momentary and fitful sunburst of the individual psychological subject has always seemed exceedingly relevant:

[....] Something on the order of a subject can be discerned on the recording surface: a strange subject, with no fixed identity, wandering about over the body without organs, yet always remaining peripheral to the desiring-machines, being defined by the share of the product it takes for itself, garnering here, there, and everywhere a reward, in the form of a becoming or an avatar, being born of the states that it consumes and being reborn with each new state: “c’est donc moi, c’est donc à moi! …” The subject is produced as a mere residue alongside the desiring machines: a conjunctive synthesis of consumption in the form of a wonderstruck: “c’était donc ça!”

[....] Such an account has the additional merit of linking up with the great Lacanian theme of “second death,”9 and of suggesting why death and resurrection should have been so stimulating a fantasy-material for a poet intent on capturing the highs and the “elevations” of an intermittent experience of subjectivity. If the subject exists always and only in the moment of rebirth, then the poetic fantasy or narrative process must necessarily first work its way along the path of death, in order to merit this unique “bonus of pleasure” whose place is carefully prepared in advance for it in the empty, dusted, polished, flower-laden chamber. And the latter is of course, for us, as readers, the poem itself: the chamber of the sonnet, Donne’s “pretty room” (and Mallarmé’s), waiting to be the faithful (and joyous) occasion of our own brief, fitful, punctual exhilaration as subjects: “c’est donc moi, c’est donc à moi!”

[....] Burke’s problem, as he confronted an analogous and historically equally new form of affect—the sublime—was to find some explanation—not for our aesthetic pleasure in the pleasurable, in “beauty,” in what could plausibly gratify the human organism on its own scale, but rather for our aesthetic delight in spectacles which would seem symbolically to crush human life and to dramatize everything which reduces the individual human being and the individual subject to powerlessness and nothingness. Burke’s solution was to detect, within this peculiar aesthetic experience, a relationship to being that might as well have been described as epistemological or even ontological (and incidentally a logic which is rigorously un-or a-symmetrical to that of his other term, “beauty”): astonishment, stupor, terror—these are some of the ways in which the individual glimpses a force which largely transcends human life and which Burke can only identify with the Godhead or the divine. The aesthetic reception of the sublime is then something like a pleasure in pain, in the tightening of the muscles and the adrenaline rush of the instinct of self-preservation, with which we greet such frightening and indeed devastating spectacles.

[....] What can be retained from this description is the notion of the sublime as a relationship of the individual subject to some fitfully or only intermittently visible force which, enormous and systematized, reduces the individual to helplessness or to that ontological marginalization which structuralism and poststructuralism have described as a “decentering” where the ego becomes little more than an “effect of structure.” But it is no longer necessary to evoke the deity to grasp what such a transindividual system might be.

[....] What has happened to the sublime since the time of Burke—although he judiciously makes a place for a concept which can be most useful to us in the present context, namely the “artificial infinite”—is that it has been transferred from nature to culture, or the urban. The visible expression of the suprapersonal mode of production in which we live is the mechanical, the artificial, the machine; and we have only to remember the “sublime” of yesterday, the exhilaration of the Futurists before the machine proper—the motorcar, the steamship liner, the machine gun, the airplane—to find some initial contemporary equivalent of the phenomenon Burke first described. One may take his point about self-preservation, and nonetheless wish to formulate this affective mechanism a little more sharply: I would have said myself that in the face of the horror of what systemically diminishes human life it becomes possible simply to change the valence on one’s emotion, to replace the minus sign with a plus sign, by a Nietzschean effort of the will to convert anxiety into that experience physiologically virtually identical with it which is eagerness, anticipation, anxious affirmation. And indeed, in a situation of radical impotence, there is really little else to do than that, to affirm what crushes you and to develop one’s capacity for gratification in an environment which increasingly makes gratification impossible.

* * *

Jay

6 October 2024