Readers unfamiliar with "Pumpkin" by Bill Pronzini may prefer to read these notes only after reading the story.

The road climbed up a bare-backed hill, and when she reached the crest Amanda stopped the pickup to admire the view. She never tired of it, especially at this time of year and on this sort of crisp, clear early fall day. The white farm buildings lay in a little pocket directly below, with the fields stretching out on three sides and the ocean vast and empty beyond.

The pumpkins were ripe now, the same bright orange as the lettering on the sign—Connecticut Field for the most part, with a single parcel devoted to Small Sugar; hundreds of them dotting the brown and green earth like a bonanza of huge gold nuggets, gleaming in the afternoon sun. The sun-glare was caught on the ruffly blue surface of the Pacific, too, so that it likewise held a sheen of orange-gold.

"Pumpkin," a story of rural agricultural life and the woes of marriage clocked by the seasons, is a fine Halloween horror tale. Amanda and Harley Sutter are depicted as real people, small capitalist farmers able to hire seasonal labor, and moving heaven and earth at harvest time to ensure their financial prosperity.

Into a crowded September comes a shard of alienage:

At first Amanda noticed nothing out of the ordinary. It seemed to be just another Connecticut Field, larger than most though nowhere near exhibition size, a little darker orange than most. But then she moved closer, and she saw that it was . . . different. She couldn’t have said quite how it was different, but there was something . . .

“Well?” Harley said to Manuel. “What about it?”

“You don’t feel it, senor?”

“No. Feel what?”

But Amanda felt it. She couldn’t have explained that, either; it was just an aura, a sense of something emanating from the pumpkin that made her uneasy, brought primitive little stirrings of fear and disgust into her mind.

“I do, Harley,” she said, and hugged herself. “I know what he means.”

“You too? Well, I still say it’s nonsense. I’m going to cut it and be done with it. Manuel, let me have your knife . . .”

Manuel backed away, putting his hand over the sharp harvesting knife at his belt. “Por Dios, no, Mr. Sutter. No. You must not!”

“Harley,” Amanda said sharply, “he’s right. Leave it be.”

“Damn. Why should I?”

“It is evil,” Manuel said, and looked away from the pumpkin and made the sign of the cross. “It is an evil thing.”

“Oh, for God’s sake. How can a pumpkin be evil?”

Amanda remembered something her uncle, who had been a Presbyterian minister, had said to her when she was a child: Evil takes many forms, Mandy. Evil shares our bed and eats at our own table. Evil is everywhere, in every size and shape.

She said, feeling chilled, “Harley, I don’t know how, I don’t know why, but that pumpkin is an an evil thing. Leave it alone. Let it rot where it lies.”

Manuel crossed himself again. “Yes, senora! We will cover it, hide it from the sun, and it will wither and die. It can do no harm if it lies here untouched.”

Later:

She went out to sit on the porch, bundled up in her heavy wool sweater, as night came down and blacked out the last of the sunset colors over the ocean. An evil pumpkin, she thought. Good Lord, it was ridiculous—a Halloween joke, a sly fantasy tale for children like those her father used to tell of ghosts and goblins, witches and warlocks, things that went bump in the dark Halloween night. How could a pumpkin be evil? Pumpkins were about as harmless a fruit as there was. You made pies and cookies from them, you carved them into grinning jack-o’-lanterns; they were a symbol of a grand old tradition, a happy children’s rite of fall.

And yet . . .

When she concentrated she could picture the way the strange pumpkin had looked, feel again the vague aura of evil that radiated from it. A small shiver passed through her. Why hadn’t Harley felt it too? Some people just weren’t sensitive to auras and emanations, she supposed that was it. He was too practical, too logical, too much of a skeptic—a true son of Missouri, the “Show Me” state, where he’d been born. He simply couldn’t understand.

How did the damned thing get in their field? Where did it come from?

What was it?

She found herself looking out toward the east field, as if the pumpkin might somehow be pulsing and glowing under its plastic covering, lighting up the night. There was nothing to see but darkness, of course. Silly. Ridiculous. But if it were picked . . . she did not want to think about what might happen if that woody, furrowed stem were sliced through, that thick dark orange rind cracked open.

The strange pumpkin, though, cannot simply be left to rot. Events conspire. Like a color out of space, our first glimpse of its impact foreshadows doom. And doom not just for married pumpkin farmers.

* * *

I have not previously read Bill Pronzini's fiction. His reputation as an anthologist, though, precedes him. In high school I was fortunate enough to read The Arbor House Treasury of Horror and the Supernatural (1981), stocked by the local library.

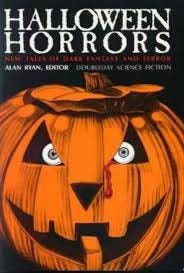

"Pumpkin" initially appeared in Halloween Horrors (1986), edited by the sorely missed writer Alan Ryan. Halloween Horrors is an anthology worth seeking by readers who enjoy fiction of the era.

Jay