For several decades I skipped "The Repairer of Reputations" in The Dark Descent. No matter which direction I took through the book, the story was too strange and off-putting for me to take a chance. I preferred the seemingly companionable authorial voice of Le Fanu and James.

My reading diary documents the day all that changed, 1 June 2019.

Do the readers of "The King in Yellow" all go mad via the same delusions? Do they, like Hildred Castaigne, imagine they are the rightful heir to the Dynasty in Carcosa? That they must rule under the Yellow Sign? Or is Hildred the only sufferer from this delusion? His mantle is crowded, after all, with Napoleon biographies.

The world of "The Repairer of Reputations" is a richly imagined fiction. We cannot see the scaffolding behind the narrative plaster; narrator Hildred is only given a few chances to show his rhetorical unreliability.

The story repays immediate and repeated rereading. It is a beauty.

* * *

I completed an initial read of the Delphi Classics ebook Complete Weird Tales of Robert W. Chambers on 9 June 2019.

The early stories of Chambers are glutted with contradictions of their period, the rosy-fingered dawn of Washington's imperial ascendancy.

Our narrator in "The Repairer of Reputations" (1895) seems to model himself, at least in his grasping arrogance, on Theodore Roosevelt. (Anyone who has not read Richard Hofstadter on T.R. should stop avoiding the pleasure). Otherwise, our narrator Mr. Castaigne might just as well be another psychotic Bonaparte manque.

Was Chambers the first to write about the mind-shattering effects of a book? (He certainly would not be the last; his pastichists may never outnumber Lovecraft's, but like readers of The King in Yellow they are multiplying).

.....During my convalescence I had bought and read for the first time, The King in Yellow . I remember after finishing the first act that it occurred to me that I had better stop. I started up and flung the book into the fireplace; the volume struck the barred grate and fell open on the hearth in the firelight. If I had not caught a glimpse of the opening words in the second act I should never have finished it, but as I stooped to pick it up, my eyes became riveted to the open page, and with a cry of terror, or perhaps it was of joy so poignant that I suffered in every nerve, I snatched the thing out of the coals and crept shaking to my bedroom, where I read it and reread it, and wept and laughed and trembled with a horror which at times assails me yet.

Readers who enjoy tales of weird travails of artists and their connoisseurs have long prized tales like "Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter" and "The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers."

"The Mask" (1895) gives a briefer view, but no less telling for that. (Do writers still have friends who paint and sculpt, and do they still visit their studios for slices of life? Or is an appetite for the moveable feast defunct? Who today realizes Pickman would have smelled of linseed oil and turps, and had a cadmium cough?)

..... "What you tell me of seeing Boris bending over you while you lay ill, and feeling his touch on your face, and hearing his voice, of course troubles me. This that you describe must have happened a fortnight after he died. I say to myself that you were dreaming, that it was part of your delirium, but the explanation does not satisfy me, nor would it you."

"In the Court of the Dragon" (1895):

....I was worn out by three nights of physical suffering and mental trouble: the last had been the worst, and it was an exhausted body, and a mind benumbed and yet acutely sensitive, which I had brought to my favourite church for healing. For I had been reading The King in Yellow.

"The sun ariseth; they gather themselves together and lay them down in their dens." Monseigneur C—— delivered his text in a calm voice, glancing quietly over the congregation. My eyes turned, I knew not why, toward the lower end of the church. The organist was coming from behind his pipes, and passing along the gallery on his way out, I saw him disappear by a small door that leads to some stairs which descend directly to the street. He was a slender man, and his face was as white as his coat was black. "Good riddance!" I thought, "with your wicked music! I hope your assistant will play the closing voluntary."

With a feeling of relief — with a deep, calm feeling of relief, I turned back to the mild face in the pulpit and settled myself to listen. Here, at last, was the ease of mind I longed for.

"My children," said the preacher, "one truth the human soul finds hardest of all to learn: that it has nothing to fear. It can never be made to see that nothing can really harm it."

"Curious doctrine!" I thought, "for a Catholic priest. Let us see how he will reconcile that with the Fathers."

"The Yellow Sign" (1895):

....I did not know whether it was something in the turpentine or a defect in the canvas, but the more I scrubbed the more that gangrene seemed to spread. I worked like a beaver to get it out, and yet the disease appeared to creep from limb to limb of the study before me. Alarmed, I strove to arrest it, but now the colour on the breast changed and the whole figure seemed to absorb the infection as a sponge soaks up water. Vigorously I plied palette-knife, turpentine, and scraper, thinking all the time what a séance I should hold with Duval who had sold me the canvas; but soon I noticed that it was not the canvas which was defective nor yet the colours of Edward. "It must be the turpentine," I thought angrily, "or else my eyes have become so blurred and confused by the afternoon light that I can't see straight." I called Tessie, the model. She came and leaned over my chair blowing rings of smoke into the air.

"What have you been doing to it?" she exclaimed

"Nothing," I growled, "it must be this turpentine!"

"What a horrible colour it is now," she continued. "Do you think my flesh resembles green cheese?"

"No, I don't," I said angrily; "did you ever know me to paint like that before?"

"No, indeed!"

"Well, then!"

"It must be the turpentine, or something," she admitted....

"The Demoiselle d'Ys" (1895):

"The moor is wild and desolate. It is easy to enter, but sometimes they who enter never leave it. There are no peasants' huts here."

A beautifully observed story set in the Breton moorland.

"The Maker of Moons" (1896) is a brilliantly executed and powerful fantasy about the interpenetration of worlds, ours and a weird China, one of whose wizards comes to live in and alter our reality. For a time. This story sends its echoes forward to works like Machen's "N." and King's "Crouch End."

....We never were able to find either her dwelling place or the glade and the fountain again. The only thing that remains to her of her former life is the gold serpent in the Metropolitan Museum and her golden globe, the symbol of the Kuen–Yuin; but the latter no longer changes color.

"A Pleasant Evening" (1896) offers more atelier life.

"....They say she is idle and vain and pleasure-loving; they say she is hare-brained and reckless. The little sculptor on the ground floor, who was buying rolls from old Cabane, spoke to me to-night for the first time, although we have always bowed to each other. He said she was very good and very beautiful. He has only seen her once, and does not know her name. I thanked him; — I don't know why I thanked him so warmly. Cabane said, 'Into this cursed Street of the Four Winds, the four winds blow all things evil.' The sculptor looked confused, but when he went out with his rolls, he said to me, 'I am sure, Monsieur, that she is as good as she is beautiful.'"

"The Messenger" (1897) is

not an antiquarian, but a spectral archeology story, again told by an American in Brittany. He is wed to a local woman with famous antecedents.

"....There was one in the last century, here in St. Gildas. He cast a white shadow in the sun. He wrote in the Breton language. Chronicles, too, I believe. I never saw them. His name was the same as that of the old chronicler, and of the other priest, Jacques Sorgue. Some said he was a lineal descendant of the traitor. Of course the first Black Priest was bad enough for anything. But if he did have a child, it need not have been the ancestor of the last Jacques Sorgue. They say this one was a holy man. They say he was so good he was not allowed to die, but was caught up to heaven one day," added Lys, with believing eyes.

I smiled.

"But he disappeared," persisted Lys.

"I'm afraid his journey was in another direction," I said jestingly, and thoughtlessly told her the story of the morning. I had utterly forgotten the masked man at her window, but before I finished I remembered him fast enough, and realized what I had done as I saw her face whiten.

"Lys," I urged tenderly, "that was only some clumsy clown's trick. You said so yourself. You are not superstitious, my dear?"

Her eyes were on mine. She slowly drew the little gold cross from her bosom and kissed it. But her lips trembled as they pressed the symbol of faith.

* * *

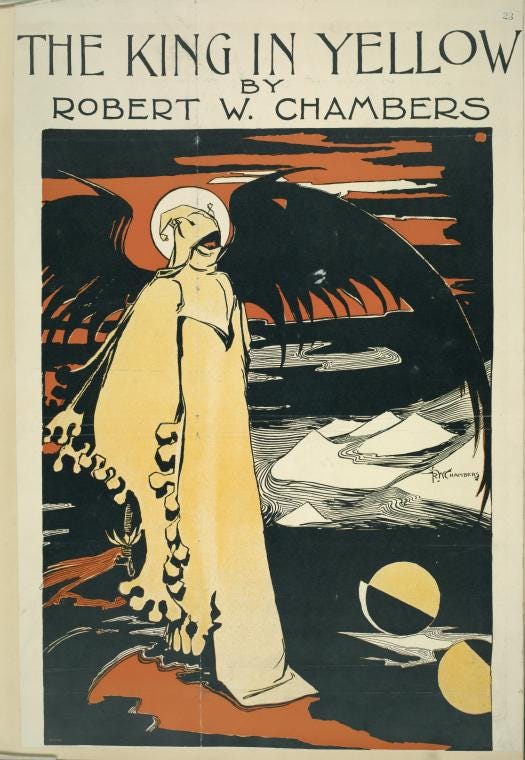

Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933)

My most recent Chambers note was made [28 November 2022] as I slogged through the anthology The Hastur Cycle (2006, Second Revised Edition), edited by Robert M. Price. I was in rehab with a broken leg at the time.

"The Repairer of Reputations" (1895) by Robert W. Chambers, however, strikes the reader as ever-new. Surprising turns and dramatic immediacy abound on every page, and there are always new levels of unreliability to be uncovered as we come to grips with the narrator. It is a richly imagined story, seemingly retconned from a megalomaniac's LARPing fantasies.

"The Yellow Sign" (1895), also by Chambers, is more modest than "The Repairer of Reputations" in its scope. An atelier horror story, it depicts an intensifying folie à deux between an artist and his model. Their conscious determination never to read Act Two of the play "The King in Yellow" is thwarted at every step; the story's atmosphere of thickening inevitability echoes Le Fanu's 1839 masterpiece "Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter" and Dorothy L. Sayers' 1928 story "The Man with Copper Fingers."

"The Yellow Sign" ends with its narrator halfway through a sentence, just before receiving the last rites. Between this ending and Karl Edward Wagner's phantasmagoria "The River of Night's Dreaming," no beat is skipped.

* * *

In his entry on Chambers in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986), the peerless

T. E. D. Klein sums up:

Chambers’s supernatural tales are facile, in the best and worst senses of the word: his writing is elegant, witty, and often lyrical, but it frequently seems shallow and devoid of feeling—marred, as Joshi has said, by “flippancy, pseudo-sophistication, and catch-penny sentimentality." Nonetheless, early works such as The King in Yellow still create a powerful atmosphere of futility and doom. The book’s first four stories arc loosely connected, dealing with luckless people who’ve dared to glance into the text of an infamous play entitled “The King in Yellow,” from which tantalizing brief quotations are offered in the stories and their epigraphs....

* * *

Matt Cowan points readers of his Horror Delve blog to the best Chambers stories here and here.

Jay

26 May 2023

Robert W. Chambers (1865-1933)