Readers unfamiliar with The Curse may prefer to read these notes only after reading the novel.

The Curse is a novel published in 1977; it is also a novel of 1977.

Middle class anxieties and a looming capitalist economic crisis mark its protagonists as the story opens. The weight of the then-militant movement for Native American civil rights and self-determination, the American Indian Movement, also obliquely manifests as a pivotal plot point in the novel.

The Curse braids into this mix of middle class anxieties the “woe that is in marriage.” This is hardly a theme exclusive to Charles L. Grant. John Updike, a writer who focused on a similar social milieu, repeatedly addressed the same class and sex-role contradictions throughout his own career, albeit from a non-horror perspective

Financial woes and patriarchal frictions beset wife and husband, Terry and Syd Guiness, as The Curse begins. Syd works at an ad agency in NYC prone to layoff rumors. Terry is a freelance book illustrator struggling to find freelance work.

The asymmetry in the marriage is expressed in Syd’s use of the word “angel” as a term of endearment for Terry. “Angel” more than hints at objectification and dismissal. He uses the term forty-one times in a novel of under two hundred pages, which says more about Syd than his attestations of love and loyalty.

* * *

Rent was so easy—one year at a time, and leases painlessly broken when the other tenants became annoyances or the apartment too crowded for their accumulation of memorabilia. A house; and she shivered in spite of the heat, and the lackluster shade. The responsibility, the mortgage, the absolute frightening permanence of everything owning a home implied. After all, she was only twenty-seven—much too young to be rooted like that scarred elm in the back, too full of wings to piece together a permanent nest. It occurred to her as she watched Syd pace off the width of the lawn that he was somehow trying to transform her, mold her Pygmalion-like into a suburban robot that cleaned and dusted and polished and waxed at the mere flick of a marital switch. How could she possibly make progress in her fledgling career and keep a house—so goddamned big, for God's sake from deteriorating into a private, thirty-year indentured slum? It was beyond her, above her, a too powerful giant for her puny female Jack.

The first two chapters of The Curse explore the tumult and disorientation Terry and Syd suffer when they decide to buy a home outside the city. Syd has secretly amassed a sizable nest egg to make a down payment.

Terry and Syd ultimately pick a property on Prynne Lane, which is just off Hawthorne Street – somewhere in “the low hills between New Jersey and Pennsylvania.” Hawthorne Street is a recurring site for Grant's stories, and The Curse adds amplitude to tales we've already read in the collection Tales from the Nightside (1981).

* * *

As Terry and Syd unpack, they are visited by neighbor Denver McIntyre and his two little grandsons. Mr. McIntyre fills them in on some of the region's history.

"Shortly after 1865," McIntyre said with his face tilted toward the ceiling, "the government became afraid that what remained of the few Eastern tribes would try to emulate their Western brothers and do some damage to the white centers of population and industry. Accordingly, the bureaucrats lumbered their agencies into action and rounded up as many scattered families as they could find without actually combing every hill and valley. Delaware, Lenape, Algonquin, and others were persuaded by various means to settle temporarily in this valley until such time as more permanent and fertile accommodations could be found and made available. Some of them came willingly, while others chose to flee after citing past government records; these, as it turned out, were the more intelligent, and lucky."

"We got wiped out bang," one of the boys said suddenly, and McIntyre quieted him with a stern pat on the head.

Then he shrugged ruefully. "But it's true. Naturally you won't find any of this in the files of the Bureau—"

"—Of Indian Affairs," Syd said, apparently miffed that he was slowly being eased out of the conversation circle. Terry exaggerated a pout and he glared at her.

"Right, Syd. So, we have to rely on others to get the full story. Oral tradition among my own people—and in several others if you have the time to search and listen—this tradition tells us that in June of 1875 a complement of federal troops set all the families who'd managed to survive the previous winters into a stockade out where the meadow is now. Legend says it was on the hill, but no one knows for sure."

"Bang," the boy said again, was echoed by his brother.

"Bang," McIntyre said sadly. "Someone gave the order and the entire Indian community was massacred without explanation. They weren't given a chance to defend themselves, nor were they given an option to move elsewhere. Ironically," he said further as Terry was about to comment, "this also happens to be the place where supposedly a chief of greater antiquity than even myself was slaughtered by a race of men neither red nor white. Some say giants, some say creatures half animal, half god. At any rate, the legends don't ascribe a particularly joyful history to Prynne Lane and its environs."

"My God," Syd said, his face as pale as if it had happened that afternoon.

"How horrible," and Terry wined at the parlor liberal sound of it, winced even more when she thought it would make a hell of an exciting story for a new series she could write as well as illustrate.

"Horrible, yes, but more then than now," said McIntyre. "Myself, I'm Shawnee, and although there were reputedly some of us here—which I am often inclined to doubt—I really don't feel like running out and scalping every white man I see. It would be hell on the neighborhood, believe me."

He laughed, and Terry was glad to laugh with him.

As summer shifts to autumn, Terry and Syd come across dead animals, drained of blood, on their property. And over a nearby hill: an engraved marker like a standing stone in the ground. Denver's adult son William tells Terry the inscription reads "'To the old ones, Rest'.” Terry sketches the marker, and decides to write her first book about it and Denver's stories.

"William," she called over her shoulder, "Denver said something to us about giants and things—or was it giants or things?—anyway, something that had been here before the reservation, eons before. Do you know anything about it?"

When she turned back for an answer, he hadn't moved except to face her. There was a faint thrumming, and the angry red sun made her blink tears away. When she recovered, rubbing her head against the possibility of a headache, William stood beside her, the box of charcoal in his hand.

"It's only a story, Mrs. Guiness. It was invented by those who came after to explain why the graves are unmarked except for. . ." and he gestured over his shoulder. "It's a way of saving face, by saying the bodies were slaughtered for god food." He smiled, and she was startled. "We all have our pride, Mrs. Guiness, but sometimes the Indian feels a need to embellish."

After the new year, Terry and Syd intensify their research on the Prynne Lane area's history as they interact with more neighbors. A book on local legends reveals:

The fourth chapter…. startled her. She looked around quickly, as though expecting someone to be reading over her shoulder, then looked down at the page her finger pressed flat. A badly drawn, but determined profile of a man. An Indian. The caption identified him as Tecumseh; a Shawnee chief who had tried to unite the wilderness tribes into an effectual force against the inexorable encroachment of early nineteenth century settlers. In spite of the portrait's poor reproduction, the messianic quality was disturbingly evident. She held the picture away from her, hoping distance would clarify a nagging hint of recognition. She tilted it, brought it closer, but the changes in perspective accomplished nothing. Maybe I need glasses, she thought, when she glanced up to rest her eyes, she realized much of the problem was the unnoticed haze of twilight. The sun was already below the treeline, and there were black strands of cloud rising like smoke from the serrated horizon.

She was about ready to stand when she heard a door slam, and without knowing why, she sat again and waited. The hedge, and the fact that she was still in the dogwood's pool of shadow, made her effectively invisible. Footsteps, then, striding along the tarmac, and as the streetlights winked on and added a blue glow to dusk, she saw Denver moving purposefully past her house toward the field. She stared openmouthed, then sucked in her cheeks and bit down to stifle an exclamation of surprise. As he passed the gap in the hedge, he glanced in her direction, and his teeth were white in a brief and unpleasant smile.

Terry shook her head, crawled out from under the branches and knelt by the hedge, poking her head out to watch as McIntyre disappeared into the birch without making a sound. He was carrying what seemed to be a glass from which he drank as the darkness swallowed him. The temptation to follow brought Terry to her feet, but the sharp creak of her own front door forestalled her, and she turned.

Syd was beckoning from the porch, and the brusqueness of the motion warned her not to risk ignoring him.

By the apocalyptic final two chapters of The Curse, Terry has connected Prynne Lane to the legacy of Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet, and to the Ghost Dance performed by Native Americans. Denver, as William explains to Terry, is confident in an indigenous belief in the coming of a secret messiah as foretold by an occult understanding of the dance.

These elements drive toward a moment of anagnorisis – when she is told, "There will be a reason for your dying."

The Curse tells an ambitious story. By its end, amid desperate action, the colonial-settler bastion of Prynne Lane may be finished.

* * *

Can the novel be read as an allegory of dispossession of Native American people? In the opening chapters of The Curse, Terry and Syd leave apartment life for home ownership: they “go west” into the borderland of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, recapitulating in miniature the westward expansion of the early U.S. republic.

Grant suggests that whatever physical or metaphysical force has employed the curse may predate Native American settlement of the area. The Curse also suggests Native Americans might have fought this entity before being driven off the land by settlers from the Atlantic seaboard. Which begs the question: who cursed or was cursed?

The end of The Curse features both a symbolic and definitive foreclosure on the Guiness's ownership/mortgage of the property.

* * *

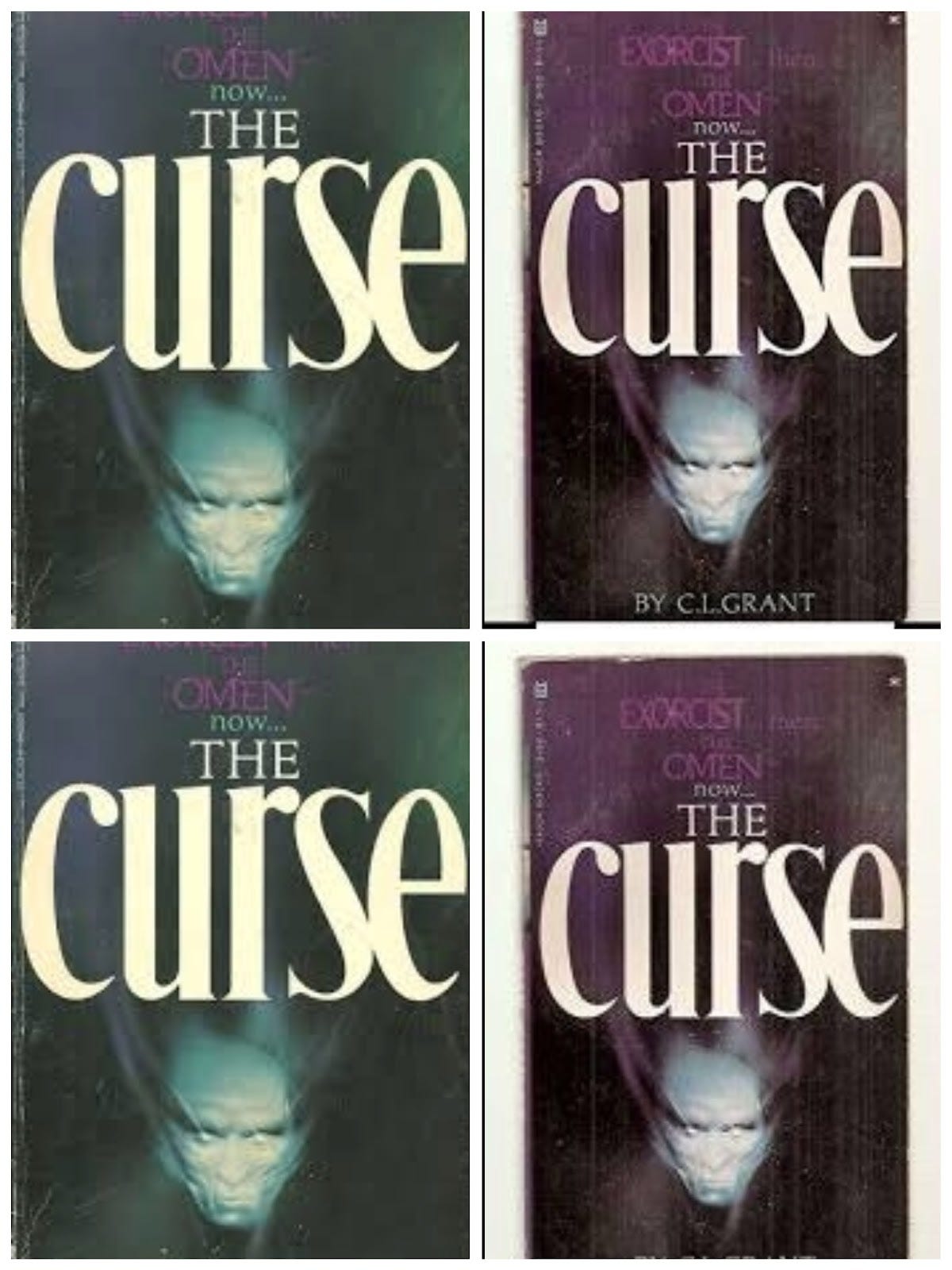

The Curse is not a "grand scale" horror novel. In 1977 this was not unusual. Prior, only The Exorcist and Harvest Home made an impact with page counts over 400. 600+ page money-spinners were still a few years away from glutting the market and warping the horror novel's scope.

Grant expertly deploys ostranenie/estrangement storytelling devices in portraying time dilations, strange sights, and peripheral impressions that keep his protagonists on the wrong foot as they confront each new plateau of crisis. But the brevity of The Curse works against some of its strongest plot elements. Foremost, these include the showdown between the Guiness and McIntyre households. The enigma of a recrudescent American Indian political messiah suffers: underpowered through lack of complication and truncated development.

Jay

29 May 2024