Readers unfamiliar with The House on the Borderland may prefer to read these notes only after reading the novel.

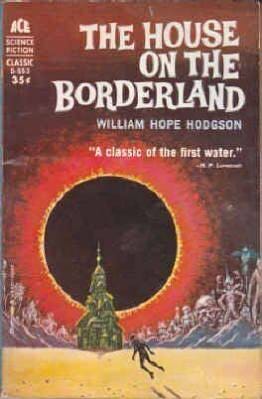

William Hope Hodgson triple-bagged The House on the Borderland (1908) with three paratextual frames.

The first, the verse "To My Father," precedes the author's introduction signed by William Hope Hodgson himself; this is the poem that introduces the term "shoon", from Scottish dialect. Hence, footsteps -- and there many heard in this novel -- are metonymically rendered "shoon."

Of vanishing shoon—

Out in the night with the Dead.

The second frame, signed "WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON December 17, 1907," ends with a further stroke of distancing and familiar/unfamiliar uncanniness:

[....] A small book it is; but thick, and all, save the last few pages, filled with a quaint but legible handwriting, and writ very close. I have the queer, faint, pit-water smell of it in my nostrils now as I write, and my fingers have subconscious memories of the soft, "cloggy" feel of the long-damp pages....

Of the simple, stiffly given account of weird and extraordinary matters, I will say little. It lies before you. The inner story must be uncovered, personally, by each reader, according to ability and desire. And even should any fail to see, as now I see, the shadowed picture and conception of that to which one may well give the accepted titles of Heaven and Hell; yet can I promise certain thrills, merely taking the story as a story.

* * *

The third framing for the notebook's narrative is Chapter One: The Finding of the Manuscript.

Berreggnog, the narrator, and his friend Tonnison set out for two weeks of camping and fishing in Ireland.

[....] It was Tonnison’s idea to camp out instead of getting lodgings in one of the cottages. As he put it, there was no joke in sleeping in a room with a numerous family of healthy Irish in one corner, and the pig-sty in the other, while over-head a ragged colony of roosting fowls distributed their blessings impartially, and the whole place so full of peat smoke that it made a fellow sneeze his head off just to put it inside the doorway....

Though the narrator advises they are in an isolated and "unpeopled" area, there seem to be a number of silently observant peasants around in this chapter, and at the end of the novel when we return to this strangely populous frame in chapter twenty-seven.

William Hope Hodgson's goal in the first chapter, like Shiel's in The Purple Cloud, is to declare victory in the forward charge to deliver the reader to the main tale. Today, creative writers would never imagine beginning a story -- to be filled with cross-purposes of its own -- so far back out from the main source of action. If I may editorialize: that is a misfortune for today's creative writers and creative readers.

* * *

As the main action of Borderland begins in chapter two, ostranenie multiplies.

In his 2020 introduction to Poison Pen Press's "Haunted library of horror classics" edition of The House of the Borderland, Ramsey Campbell attests:

[....] The afterlife is glimpsed but remains ungraspable, not least because the account of it disintegrates. [Emphasis mine-JR]

[....] In our field, mystery and enigma can be more satisfying than any explanation, and Hodgson’s novel keeps its secrets as it extends its scope…. A journey to the end of time, reminiscent of The Time Machine but vividly reimagined, eventually returns us to the extraterrestrial house and thence to the earthly one. Perhaps these weird voyages destabilise the building, though the foundations may well have been weakened by an onslaught of water in a scene evoking the terrible power of that medium (a recurring motif in Hodgson’s work, drawing on his maritime experiences), but how do they affect the hermit’s mind? [Emphasis mine-JR]

[....] At times it feels as if the various dimensions—spatial, temporal, spiritual—to which the building is a portal, may burst the narrative apart just as they apparently undermine the house... (Hodgson 10-11)

* * *

Chapter XXVII returns the reader to Tonnison and Berreggnog as they finish their two-week vacation. Once their driver returns

[....] both together, almost in the same breath, we asked the question that was uppermost in our minds:—Did he know anything about an old garden, and a great pit, and a lake, situated some miles away, down the river; also, had he ever heard of a great house thereabouts?

No, he did not, and had not; yet, stay, he had heard a rumour, once upon a time, of a great, old house standing alone out in the wilderness; but, if he remembered rightly it was a place given over to the fairies; or, if that had not been so, he was certain that there had been something “quare” about it; and, anyway, he had heard nothing of it for a very long while—not since he was quite a gossoon. No, he could not remember anything particular about it; indeed, he did not know he remembered anything “at all, at all” until we questioned him.

[....] The substance of this knowledge was, that, in the “ancient man’s” youth—and goodness knows how long back that was—there had stood a great house in the centre of the gardens, where now was left only that fragment of ruin. This house had been empty for a great while; years before his—the ancient man’s—birth. It was a place shunned by the people of the village, as it had been shunned by their fathers before them. There were many things said about it, and all were of evil. No one ever went near it, either by day or night. In the village it was a synonym of all that is unholy and dreadful.... (Hodgson 165)

Village rumors recount the arrival of the diarist narrator and his sister, and their monthly visit of the supply deliveries. Until, on the last delivery day, the supplier reports:

....the House had disappeared bodily, and that a stupendous pit now yawned in the place where it had stood. (Hodgson 166)

* * *

After Chapter XXVII, The House On The Borderland provides a final poem, more subjectively personal than the "Shoon of the dead" opening verse. It is presented as an addendum to the narrator's diary.

My breast is one whole raging pain

For that which was, and now is flown

Into the Blank where life is hurled

Where all is not, nor is again!” (Hodgson 168)

Which, to my way of reading, amounts to more mystifying deflection and strange-making. It's a superb touch, in fact unprecedented for a novel circa 1908. If contingency and indeterminacy are hallmarks of the Modern, Borderland rivals Ulysses.

* * *

The paratextual elements in the new edition of The House on the Borderland (Haunted Library Horror Classics, 2020) do not stop with the seventeen end-notes Hope Hodgson used as the original stopping-point.

Pages 171-173 provide fourteen SUGGESTED DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR CLASSROOM USE. Most of the questions are designed to elicit personal opinions, others ask students to explore questions that used to be embargoed as embracing the "intentional fallacy."

Examples:

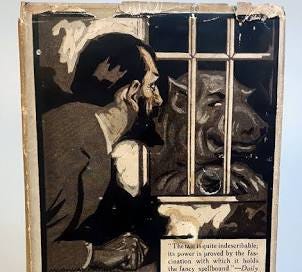

7. What is the significance of the Swine-things? Why do you think they pursue and then invade the Recluse’s home? What do they want of him?

12. What emotions did you feel while reading this book?

14. The Recluse writes in his diary, “I am not superstitious; but I have ceased to deny that things happen in this old house—things that I cannot explain…” Are there things or events in life that you have encountered or experienced and cannot explain?

* * *

After the discussion questions, the 2020 edition provides a broad and intelligent list of titles for further reading on pages 174-77. The suggestions are smart; a few examples:

American Supernatural Tales (an anthology) edited by S. T. Joshi (2007)

Claimed by Francis Stevens (1920)

Cold Hand in Mine: Eight Strange Stories by Robert Aickman (1975)

Don’t Look Now and Other Stories by Daphne du Maurier (1971)

Malpertuis by Jean Ray (1943)

The Other Side (German: Die andere Seite) by Alfred Kubin (1909)

The Room in the Tower, and Other Stories by E. F. Benson (1912)

Star Maker by Olaf Stapledon (1937)

Tales of Horror & the Supernatural (collected works) of Arthur Machen (1983)

The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories (an anthology) edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer (2012)

* * *

Inexpensive editions of The House on the Borderland have been available for over a century. Project Gutenberg reported today that in the last thirty days, The House on the Borderland has been downloaded free 563 times.

The 2020 edition is a comfort, however. Its introduction by Ramsey Campbell, for instance, shows that even a horror intellectual of over sixty years professional standing can remain stumped and tentative before this black monolith conundrum of a novel.

Reading William Hope Hodgson's novel for the first time as an adult, I am stunned by Lovecraft's skillful, pertinent, and compelling summation:

The House on the Borderland (1908)—perhaps the greatest of all Mr. Hodgson’s works—tells of a lonely and evilly regarded house in Ireland which forms a focus for hideous other-world forces and sustains a siege by blasphemous hybrid anomalies from a hidden abyss below. The wanderings of the narrator’s spirit through limitless light-years of cosmic space and kalpas of eternity, and its witnessing of the solar system’s final destruction, constitute something almost unique in standard literature. And everywhere there is manifest the author’s power to suggest vague, ambushed horrors in natural scenery. But for a few touches of commonplace sentimentality this book would be a classic of the first water.

The Ghost Pirates (1909) is, in my judgment, Hodgson's finest work. But Borderland is a novel that demands our attention as readers of horror.

Jay

14 February 2024

Work cited

Hodgson, William Hope. The House on the Borderland. Haunted Library Horror Classics, 2020.

“Supernatural Horror in Literature” by H. P. Lovecraft. www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/essays/shil.aspx