The New Aestheticism

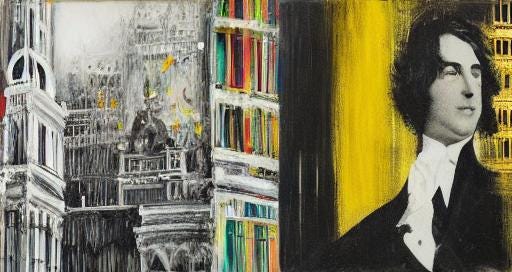

The nineties began in 1889 and ended in 1895. At least the Wildean nineties did so, and without Wilde the decade could not have found its character. These were the years in which aestheticism was revised and perfected. During the eighties, Wilde’s extremist sponsorship had helped to discredit it and provoked extravagant scorn. Now he conferred a new complexity upon the movement. Without surrendering the contempt for morality, or for nature, that had alarmed and annoyed his critics, Wilde now allowed for ‘a higher ethics’ in which artistic freedom and full expression of personality were possible, along with a curious brand of individualistic sympathy or narcissistic socialism. He also made it clear that nature might mirror, through art, what Shelley called ‘the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present.’ To these he added another feature of aestheticism, the invasion of forbidden areas of thought and behavior. Decorum became merely a formal attribute of works of art, not a question of morality.

Aestheticism in its new guise modified the relationship between reader and writer. If matter once the exclusive preserve of pornography could be broached, then the reader’s calm and sense of unthreatened distance were violable. Many young men and women learned of the existence of uncelebrated forms of love through the hints in The Picture of Dorian Gray. (Unofficially, Wilde took note of what he officially denied, and told young Graham Robertson the artist, ‘Graham, the book was not written for you, and I hope you will not read it.’) People also learned from Wilde how to shape a sentence and live in style. In the eighties, aestheticism suffered for lack of example: Dorian Gray filled the need. With its irreverent maxims, its catch phrases, its conversational gambits, its insouciance and contrariness, it announced the age of Dorian.

In the eighties, aestheticism had been less a movement than an expostulation with the lack of one. Yet its influence, and the influence of the movement of which it was a part—that propaganda for art and artist against ‘factification’ and ‘getting-on’—grew stronger. The claims of action over art were challenged by the

idea that artistic creation, related to that contemplative life celebrated by Plato, was the highest form of action. Wilde summed up ideas that were only implicit in England, but expressed in the poems of Mallarmé and Verlaine and in the novels of Flaubert and D’Annunzio. These writers propounded their positions more carefully than Wilde, but he vied with them in one respect: he was spectacular always.

He was the more spectacular because his views, which agitated among the roots of literature and life, were presented with nonchalance. The use of dialogue lent undogmatic informality to his expression. He said, ‘I can invent an imaginary antagonist and convert him when I choose by some absurdly sophistical argument.’ 1

Even when he relinquished that form, as in ‘The Soul of Man Under Socialism,’ he seemed to allow for debate with his position. It was as essential to disturb complacencies as to convince, or possibly more. In a diary for 21 July 1890 Katharine Bradley (of the ‘Michael Field’ collaboration) recorded how Wilde affirmed his role of lounge lizard:

We agreed—the whole problem of life turns on pleasure—Pater shows that the hedonist—the perfected hedonist—is the saint. ‘One is not always happy when one is good; but one is always good when one is happy.’ He is writing two articles at present in the Nineteenth Century on the Art of Doing Nothing. He is at his best when he is lying on a sofa thinking. He does not want to do anything; overcome by the ‘maladie du style’—the effort to bring in delicate cadences to express exactly what he wants to express—he is prostrate. But to think, to contemplate … 2

Wilde was referring to his articles on ‘The True Function and Value of Criticism: With Some Remarks on the Importance of Doing Nothing: A Dialogue,’ published in the Nineteenth Century in July and September 1890. In Dorian Gray, first published in Lippincott’s on 20 June 1890, Lord Henry Wotton speaks ‘languidly’ three times and ‘languorously’ once. He gave a new sanction to these words, as Verlaine had given it to ‘langueur ’ in French seven years before. Wilde was not indolent: he read voraciously, he devised and tried out conversational gambits, and touched them up in accordance with the shock, amusement, acquiescence, or delight that they aroused. He attributed the same interest in speech to the Greeks: ‘Their test was always the spoken word in its musical and metrical relations. The voice was the medium, and the ear the critic.’ He radiated, in Katharine Bradley’s words, ‘ bien être ’ with his ‘mossy voice.’ Most of his writing, Pater noted half in dispraise, had the air of ‘an excellent talker.’ 3 Yet in 1891, his annus mirabilis, he published four books (two volumes of stories, one of critical essays, and a novel) and a long political essay (‘The Soul of Man Under Socialism’) and wrote his first successful play, Lady Windermere’s Fan, as well as most of Salome. Languor was the mask of industry....

....A more total convert to Wilde than Johnson or Barlas was Max Beerbohm, who met him first in 1888, while still at school at Charterhouse, and became a friend in the early 1890s when his brother, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, produced a Wilde play. Beerbohm was quick and clever: Wilde taught him to be languid and preposterous. Beerbohm referred to Wilde as ‘the Divinity’; Wilde said that Beerbohm had ‘the gift of perpetual old age.’ If Wilde celebrated the mask, Beerbohm in his first essays would celebrate maquillage; if Wilde wrote Dorian Gray about a man and his portrait, Beerbohm would write The Happy Hypocrite about a man and his mask. To some extent the disciple went beyond the master; Wilde complained to Ada Leverson, ‘He plays with words as one plays with what one loves. When you are alone with him, Sphinx, does he take off his face and reveal his mask?’ 10 The exquisite triviality of Zuleika Dobson tried to match The Importance of Being Earnest. Its discussion of peacocks and presents came straight from Salome. Beerbohm admired, learned, and resisted; aware that Wilde was homosexual, and anxious not to follow him in that direction, he drew back from intimacy. He was to caricature Wilde savagely; this was ungrateful, but it was a form of ingratitude, and of intimacy, into which other followers of Wilde lapsed....

....For Wilde, aestheticism was not a creed but a problem. Exploring its ramifications provided him with his subject, and he responded to it with a mixture of serious espousal and mockery—an attitude that Beerbohm found it fruitful to copy. Gautier had preached an icy aestheticism—Wilde did not subscribe, but sometimes enjoyed pretending that he did. The slogan of ‘art for art’s sake’ he had long since disavowed. But he saw his story of a man and his portrait as containing most of the ingredients that he wanted to exploit. ‘To become a work of art is the object of living,’ he wrote. 12 Dorian was one of two portraits he would write of a man in decay, the other being the professed self-portrait in De Profundis. Wilde’s novel connects somewhat with other narratives. In Henry James’s The Tragic Muse, published in 1890, the aesthete Gabriel Nash bears traces of Wilde, including the aesthetic cosmopolitanism which James found so annoying in 1882. When Nick Dormer asks Nash, ‘Don’t we both live in London, after all, and in the Nineteenth Century?,’ Nash replies, ‘Ah, my dear Dormer, excuse me. I don’t live in the Nineteenth Century. Jamais de la vie! ’ ‘Nor in London either?’ ‘Yes—when I’m not in Samarcand.’ Nash sits for a portrait, but disappears: no one knows where he has gone, and his unfinished image on the canvas fades away as impalpably as the original. James’s theme was that aestheticism, being indifferent to concrete detail, could confer upon its followers only an illusory existence. But if James was hard on aestheticism, Wilde would be hard on it too, at least in his novel.

Wilde liked telling stories about portraits. Charles Ricketts remembered someone speaking to Wilde of the excellence of Holbein’s portrait of Anne of Cleves. Her ugliness had overwhelmed Henry VIII. ‘You believe she was really ugly?’ said Wilde. ‘No, my dear boy, she was exquisite as we see her in the Louvre. But in the escort, sent to bring her to England, travelled also a beautiful young nobleman of whom she became passionately enamoured, and on the ship they became lovers. What could be done? Discovery meant death. So she stained her face, and put uncouth clothing upon her body, till she seemed the monster Henry thought her. Now, do you know what happened? Years passed, and one day, when the king went hawking, he heard a woman singing in an orchard close, and rising in his stirrups to see who, with lovely voice, had entranced him, he beheld Anne of Cleves, young and beautiful, singing in the arms of her lover.’ 13

Among the many sources that have been offered for The Picture of Dorian Gray are Balzac’s La Peau de chagrin, Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Goethe’s Faust, Meinhold’s Sidonia. The list could be multiplied indefinitely. As Yeats says, ‘Works of art beget works of art.’ No specific work is exactly comparable. Wilde had hit upon a myth for aestheticism, the myth of the vindictive image, an art that turns upon its original as son against father or man against God. He began with a familiar theme: ‘I first conceived the idea of a young man selling his soul in exchange for eternal youth—an idea that is old in the history of literature, but to which I have given new form,’ he said in a letter to an editor about the book. The new form came from localizing this theme in the contemporary controversy of art versus life. That the story was as old as Salome’s did not distress him. He wanted to make Dorian a figure to vie with Marius and Des Esseintes, not to mention Balzac’s Lucien de Rubempré—and succeeded.

....No wonder he spoke often about poses and masks. ‘The first duty in life is to assume a pose,’ he said; ‘what the second duty is no one yet has found out.’ As Yeats would insist after him, the imaginative creation of oneself goes on almost from birth. He was moved by the attempt of Des Esseintes in A Rebours to construct an artistic world in which to live artistically, and he spoke approvingly in ‘Pen, Pencil and Poison’ of life as art. He disagreed with those who called him artificial. He thought of the self as having multiple possibilities, and of his life as manifesting each of these in turn.

Portraits, and mirrors, were therefore subjects for his dialectic. Mirrors may be naturalistic, as in ‘The Birthday of the Infanta,’ where the dwarf dies at the sight of his own image, or in Dorian’s favorite book, in which the hero has ‘a grotesque dread of mirrors and polished steel surfaces and still water’ because they will disclose his fading beauty. But they may also be symbolic. In Wilde’s fable, Narcissus looks at his image in the water, but does not know that the water sees only its own image in his eyes. In ‘The Decay of Lying,’ instead of art mirroring nature, nature mirrors art. The preface to Dorian Gray declares, ‘It is the spectator, and not Life, that art really mirrors,’ yet in the novel the portrait ceases to mirror Dorian’s external beauty and mirrors only his internal ugliness.

He also had in mind his controversy with Whistler, when he had argued, in his 1885 review of ‘Mr Whistler’s Ten o’Clock,’ that the supreme artist was the poet (not, as Whistler maintained, the painter), because the poet could make use of all experience rather than a part. He knew Lessing’s theory that painting was spatial and literature temporal, and ‘The Critic as Artist,’ written at the same time as Dorian Gray, insists that the time world is superior, since it involves a psychic response to one’s own history:

The statue is concentrated in one moment of perfection. The image stained upon the canvas possesses no spiritual element of growth or change. If they know nothing of death, it is because they know little of life, for the secrets of life belong to those, and those only, whom the sequence of time affects, and who possess not merely the present but the future, and can rise or fall from a past of glory or of shame. Movement, that problem of the visible arts, can be truly realised by Literature alone.

For his novel he dreamed of transcending these generic limits. It had to be written in words, but with the words he could describe a painting with the attributes Lessing had denied to pictorial art: once the portrait had transfigured its object—the sitter—by concentrating him in one moment of perfection, it would disfigure its achievement as though it would claim time rather than space. That literature and painting could not exchange their roles was the idea which Dorian Gray would alter; in the end each art would revert to its norm, but literature would show itself capable of doing what painting could not do, exist temporally rather than eternally, and yet enshrine a portrait of its beautiful and monstrous hero. Though he had removed all traces of Whistler from the book, the novel carries on their old dispute about the relative merits of their two arts. Wilde wins by bringing together, as Whistler could not, the exalted moment and its disintegration.

This concern with time reflected Wilde’s sense of his own changes. Now that he was firmly homosexual, he wondered if he had always been so. Dorian moves from innocence to guilt. Wilde did not feel particularly guilty, but he could wonder if he had ever been innocent. Had his youthful love life been only a pretense? Such questions led him to the two Dorians....

CHAPTER XII. The Age of Dorian

Oscar Wilde (1988) by Richard Ellmann