"The Portable Phonograph" (1941) by Walter Van Tilburg Clark (1909-1971)

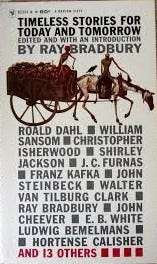

Timeless Stories for Today and Tomorrow (1952) edited by Ray Bradbury

Readers unfamiliar with "The Portable Phonograph" may prefer to read these notes only after reading the story.

West aftermath

"The Portable Phonograph" (1941) by Walter Van Tilburg Clark (1909-1971) is a brief story about what little remains after the Final War. Clark was far from alone in expressing these anxieties at the end of the 1930s.

The story's style is literate and textbook professional; little wonder, since Clark spent much of his life teaching composition and literature to undergraduates. According to his biographer, he instilled in students his passion for symbols and symbol-hunting. (Benson, 296) That the story caught Bradbury's eye speaks to that author's skill as a middlebrow anthologist.

"The Portable Phonograph" begins with an inhospitable landscape. It becomes clear to the reader that there is something more going on than cold prairie weather.

….High in the air there was wind, for through the veil of the dusk the clouds could be seen gliding rapidly south and changing shapes. A queer sensation of torment, of two-sided, unpredictable nature, arose from the stillness of the earth air beneath the violence of the upper air. Out. of the sunset, through the dead, matted grass and isolated weed stalks of the prairie, crept the narrow and deeply rutted remains of a road. In the road, in places, there were crusts of shallow, brittle ice. There were little islands of an old oiled pavement in the road, too, but most of it was mud, now frozen rigid. The frozen mud still bore the toothed impress of great tanks, and a wanderer on the neighboring undulations might have stumbled, in this light, into large, partially filled-in and weed-grown cavities, their banks channelled and beginning to spread into badlands. These pits were such as might have been made by falling meteors, but they were not. They were the scars of gigantic bombs, their rawness already made a little natural by rain, seed, and time. Along the road, there were rakish remnants of fence. There was also, just visible, one portion of tangled and multiple barbed wire still erect, behind which was a shelving ditch with small caves, now very quiet and empty, at intervals in its back wall. Otherwise there was no structure or remnant of a structure visible over the dome of the darkling earth, but only, in sheltered hollows, the darker shadows of young trees trying again….

….North of the road perhaps a hundred yards, lay the parallel and deeply intrenched course of a small creek, lined with leafless alders and willows. The creek was already silent under ice. In the bank above it was dug a sort of cell, with a single opening, like the mouth of a mine tunnel. Within the cell there was a little red of fire, which showed dully through the opening, like a reflection or a deception of the imagination. The light came from the chary burning of four blocks of poorly aged peat, which gave off a petty warmth and much acrid smoke. But the precious remnants of wood, old fence posts and timbers from the long-deserted dugouts, had to be saved for the real cold, for the time when a man’s breath blew white, the moisture in his nostrils stiffened at once when he stepped out, and the expansive blizzards pa- raded for days over the vast open, swirling and settling and thickening, till the dawn of the cleared day when the sky was thin blue-green and the terrible cold, in which a man could not live for three hours unwarmed, lay over the uniformly drifted swell of the plain....

Aside from observing frozen tank tracks and weathered bomb craters, Clark and his characters say nothing to characterize their war. Clark does show that it probably spelled the end of human society: material resources for the continuation of social life no longer exist.

The three men gathered in Dr. Jenkins' bolt-hole, dug into the bank above a frozen stream, have come together to remember what is lost.

“When I perceived what was happening,” [Jenkins] said, “I told myself, ‘It is the end. I cannot take much; I will take these.’

“Perhaps I was impractical,” he continued. “But for myself, I do not regret, and what do we know of those who will come after us? We are the doddering remnant of a race of mechanical fools. I have saved what I love; the soul of what was good in us is here; perhaps the new ones will make a strong enough beginning….”

“Shakespeare, the Bible, ‘Moby Dick,” the ‘Divine Comedy,’ ” one of them said softly. “You might have done worse, much worse.”

“You will have a little soul left until you die,” said another harshly. “That is more than is true of us. My brain becomes thick, like my hands.” He held the big, battered hands, with their black nails, in the glow to be seen.

“I want paper to write on,” he said. “And there is none.”

The fourth man said nothing. He sat in the shadow far- thest from the fire, and sometimes his body jerked in its rags from the cold. Although he was still young, he was sick and coughed often. Writing implied a greater future than he now felt able to consider....

"You wish to hear the phonograph,” [Dr. Jenkins] said grudgingly.

The two middle-aged men stared into the fire, unable to formulate and expose the enormity of their desire.

The young man, however, said anxiously, between suppressed coughs, “Oh, please,” like an excited child.

At the end of the story, Dr. Jenkins has no illusions. He waits in the dark--lead pipe at the ready--to fight off any house guest returning to steal his treasures

We are far from the small but affirming flames that end Earth Abides (1946) and Alas, Babylon (1959). The landscape and interior of "The Portable Phonograph" is closer to the roadside of Waiting for Godot (1953) and the bunker of Fin de partie (1957).

Even the petty-bourgeois moralizing irony of a TV intellectual like Rod Serling has no role here: Dr. Jenkins may fear his fellow man, but this is at best an old habit that will soon die with him.

"At the very heart of the moment of Aftermath lies an awareness that the story is done."

-- The Darkening Garden: A Short Lexicon of Horror (2004) by John Clute

Jay