The sound of pleasing terror

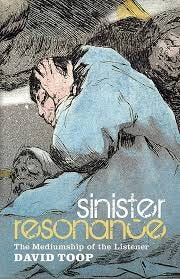

Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener (2012) David Toop

Excerpt:

TAP-TAP-TAP

Memories of fear linger, yet there is a pleasure in recalling childhood fears at a remove. Stories written by specialists in horror, haunting and the supernatural, deploy sound and silence as agents, premonitions or signs of the uncanny, those meetings with whatever lies beyond death or the limits of this world. For M. R. James, this was deeply personal. When James lived in rooms above the classics tutor, Nathaniel Wedd, in King’s College, Cambridge, he would feel real horror each night when Wedd knocked out his pipe on the mantelpiece. Even though James knew the benign source of the sound from below, tap-tap-tap, he was convinced there was a ghost in his outer room.

This is curious, that he should be so unnerved in this way as to feel haunted by what he knows is familiar and real. Clearly, James was sensitive to the uncanny atmosphere that may rise unexpectedly out of some trivial incident, a room, or even a landscape. In his story, ‘A Neighbour’s Landmark’, the narrator’s curiosity is piqued by the riddle of two lines from a country song — ‘That which walks in Betton Wood, knows why it walks or why it cries’ — in a letter written by a clergyman. The wood has been stubbed up but he explores the countryside, which seems beautifully idyllic to the point of cliché. ‘All at once I turned as if I had been stung’, James wrote. ‘There thrilled into my right ear and pierced my head a note of incredible sharpness, like the shriek of a bat, only ten times intensified — the kind of thing that makes one wonder if something has not given way in one’s brain.’ All of the complacent images that he expects as a mental corollary of the clock bell striking seven are displaced by dusty beams, creeping spiders, savage owls, forgotten graves and creeping Time. Again, he hears the piercing sound, this time in the left ear, and ‘close as if lips had been put to within an inch of my head’. He decides that the sound has an external source and thinks of a line from Tennyson: ‘With no language but a cry.’ The effect of this emotionless scream is to drive him away from a place he later discovers to be the former site of Betton Wood. The story ends inconclusively, the atmosphere of the audible ghost who defines a troubled landscape clearly being of more interest to James than a neat resolution.

The conjecture that sounds can linger in a place for centuries, long after the decomposition of physical bodies, is a theme found in other stories written by James. In ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book’, the bookish, bachelor Englishman typical of this genre visits a French church and hears stories of strange sounds. As he examines the church and its paintings, the faint noises audible all day — muffled footfalls and distant talking voices — intensify, ‘… no doubt because of the fading light and the consequently quickened sense of hearing’. This sonic prelude to a haunting also features in ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’, first published in 1904. Parkins, a Professor of Ontography (a subject that might, if it existed, describe reality), takes a short break on the coast of Suffolk, intending to improve his golf and work in seclusion on his ontographical studies. Exploring a ruined Templars’ church at the behest of a colleague of ‘antiquarian pursuits’, he pockets a small metal whistle, inscribed with Latin text that he interprets, on first reading, as ‘Who is this who is coming?’ As a test, he blows the whistle, not only raising a fierce wind, ‘moaning and rushing past the house, at times rising to a cry so desolate that, as Parkins disinterestedly said, it might have made fanciful people feel quite uncomfortable’, but also invoking the unshakeable mental image of a man pursued by a flickering, ill-defined figure in pale draperies. Amusingly, given the exclusively masculine milieu of James’s unworldly dons, the apparition conjured by the whistle first manifests its presence by twisting and crumpling the spare sheets, as if the colleague due to occupy the empty bed in his room had arrived ahead of schedule, in the form of an erotic dream. The following night, as Parkins tries to sleep, he senses a movement in this empty bed: ‘Tomorrow he would have it moved, for there must be rats or something playing about in it. It was quiet now. No! the commotion began again. There was a rustling and shaking: surely more than any rat could cause.’ The ghost takes the form of crumpled linen, blind yet alert to sound. A ‘cry of disgust’ betrays Parkins and he almost suffers the ignominious fate of losing his life at the hands of a bed sheet.

Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener (2012) David Toop

I learned a lot I didn’t k win from that. Very interesting!