"There was sun outside, the kind sun of mid-September"

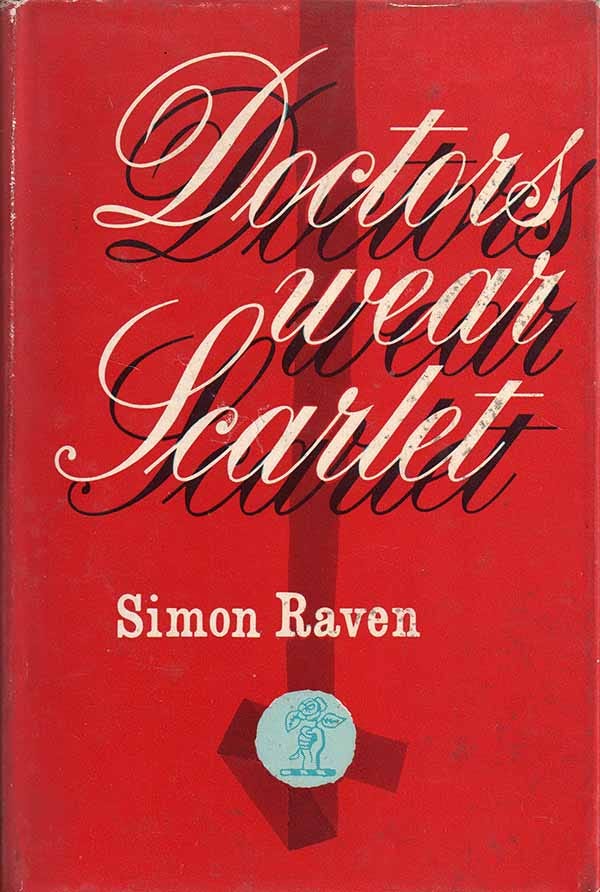

Doctors Wear Scarlet (1960) by Simon Raven

Six years ago I started reading Simon Raven's perfect Doctors Wear Scarlet (1960). I wrote after finishing it that I did not need to read another novel. I have read a handful since then, and enjoyed each. But I think my 2017 conclusion is still a sound judgment.

* * *

“Tell us what you know,” said Tyrrel abruptly. “Tell us what the superstitious say, and then what the instructed say. We must have something to go on, Erik. Do your best – and then leave the responsibility squarely with us.”

“I had no intention of leaving it anywhere else,” said Doctor Holmstrom. He tilted his chair back and sent a stream of smoke towards the ceiling. Then he sat forward again, put his chin in his left hand, and began, slowly and with great care, to tell us what he knew.

“Vampirism,” he said, “is a phenomenon popularly associated with Central and Eastern Europe. In fact, of course, it is universal – and extremely rare. The reason why we connect it so readily with the Balkan states is that it was in this part of the world that the most substantial and entertaining corpus of legend was first established. Most simple people are good at producing grim superstitions; but the Slav and Magyar inhabitants of Eastern Europe share with certain Scandinavians a genius for spicing their tales with a kind of succinct and plausible nastiness that one seldom finds elsewhere. The vampire myth was just the sort of material they needed. Hence their particular insistence on it, and hence the popular idea that vampires exist only between the Carpathian mountains and the Northern shores of the Eastern Mediterranean. In fact you will find as many, or as few, in Boston as in Budapest. But because of their skilful use of the legend, the East Europeans have a corner in vampirism; and this, roughly, is what their superstition maintains.

“It postulates a taste in a living human being for sucking the blood of other human beings. How, in the first instance such a taste should arise is uncertain; but clearly, from a purely superstitious point of view, there is a connection with the magical notion that by possessing yourself of any living part of another person or animal you increase your own power both over the creature concerned and in nature generally. Nail-parings, hair, testicles…but what could be more significant, what could possibly increase your power so much, as actually drinking human blood? In any case, there it is: a living person has this taste, and he indulges it at the expense of his fellow men. But now we come to one of the most terrifying and also most misleading aspects of the whole affair: for according to the superstition, anybody who is used by a vampire becomes infected with the taste himself. And even worse. He may die from loss of blood, he may, for whatever reason, survive; but in either case he himself has now become a vampire and as such will continue to roam the earth in search of human prey even after he has died his human death and regardless of how soon or late this may occur.

“Now, as to the exact powers enjoyed by a vampire after death, opinion differs a good deal from region to region. At one end of the scale, the vampire is credited only with the freedom to wander from his grave between sunset and sunrise. At the other extreme, he is supposed to be able to survive in all respects as a normal human being, save that he will always avoid the light of the sun as far as possible and will tend to be languid during the day time. Then there are several ancillary powers, variously affirmed and denied. Most forms of the legend maintain that vampires can induce hypnosis in their intended victims. Some versions say that after dark – whether or not he must spend the day in the tomb – the vampire can transform himself into a bat or a wolf at will – or can even change himself into a kind of thin mist, thus facilitating entrance into places where he is, for excellent reasons, unwelcome. One may remark, incidentally, that some talent of this nature is presupposed by the very condition of his existence, or how would a vampire escape from his tomb in the first place? But it is idle to insist on logic when dealing with matters of this kind. What it boils down to is that any man who has given blood to a vampire, whether to a living vampire or a ‘dead’ one, becomes a vampire in his turn and is endowed, when he dies, with some form of bodily immortality. Such a creature is nourished by human blood – though he continues to exist when deprived of it–: he dislikes sunlight, garlic, onions, salt water, and the form of the so called holy cross: he may or may not have supernatural powers other than that of surviving death: and he may or may not be able to exist unsuspected with and among other men.

“Finally, the matter of destroying such creatures. There is only one way of doing this. You must discover the vampire when he is inert and powerless, which, according to some, would be between sunrise and sunset, or according to others only when a crucifix is held straight in front of his eyes. You must then take a sharpened stake and drive it through his heart. Once this is done, the creature is finally and properly dead; and all his victims, whether ‘dead’ or still living, are now released from the spell.

“So much for the superstition. Have you any questions you would like to ask?”

“Yes,” said Tyrrel: “I once heard that vampires are able to inspire affection and even sexual passion in their victims. What would you say to this?”

“That it is true,” said Holmstrom: “literally and scientifically true. I shall come on to that in a moment.”

There was sun outside, the kind sun of mid-September; but no sun came into Holmstrom’s basement office, which might almost have been a tomb itself, so damp it was and dreary. Listening to Holmstrom’s smooth, deep voice, I had almost begun to wonder if he were not himself akin to the vampires he described so carefully – lurking down in the dark by day, emerging at night, with his bright eyes and soothing voice, to seek his victims along the dull streets of Bloomsbury. But now he rose from his chair and waddled to the door; opening it slightly, he peered out and boomed down the corridor – “Coffee for three, girl” – an earthy statement which I found somewhat reassuring.

He returned to his chair and lit a fresh cheroot.

“So much,” he said, “for the superstition. Now for what we may euphemistically call the truth.”

He chuckled obscenely – a high-pitched chuckle, in odd contrast to his mellow voice – and spat with care and accuracy into the waste-paper basket at his side.

“Yes,” he said, his face twitching with amusement, “the truth… As we understand the matter – and you must realise that only very occasional examples come to our notice – the vampire is in fact a living human being with a peculiar type of sado-sexual perversion. The sexual element is quite obvious; you might consider, in this context, such relatively normal practices as fellatio or cunnilinctus. Nor is it difficult to see that vampiric intercourse, in a quiet way, has a deeply sadistic tinge to it. It follows, of course, that the victims of vampires tend to be of a masochistic type – and like most masochists, capable of assuming a sadistic role in their turn. You should also be reminded that sadistic practices – and among them this one – are liable to have a strong appeal for impotent males or frigid females.

“But if these are the bare psychological bones, so to say, it still does not do to dismiss out of hand the corpus of superstition. Legends cast in superstitious terms have a way of reflecting scientific reality, and so it is here. Allegations of immortality can be dismissed outright: they are merely the product of the Slav imagination which, confronted with something beastly, delights to make it positively fiendish. Again, tales of transformation into, say, the shape of a bat, clearly originate from the fact that creatures called vampire bats – who amply earn their title – are well known to exist in several parts of the world. But in other ways the superstition is nearer the mark. Take this business of hypnotic powers: it is not true that an initiation into vampiric practices confers these powers; but it is true that someone who wants to indulge such abnormal and dangerous tastes must possess a very strong and alluring personality to win over his victim in the first place. Thus it is clear that something at any rate comparable to an hypnotic talent is a precondition of ever becoming a vampire. This connects very closely with what John was asking about just now – the rumoured skill of the vampire in inducing strong affections and sexual passions. Vampires as such are not endowed with this ability; but plainly it may be necessary to inspire very considerable emotions of an amorous or sexual kind before a victim can be brought to assent to the vampire’s proposition. One sums up the matter by saying that sexual magnetism, being one element in the so called hypnotic personality, is a pre-requisite of vampiric practice.

“And then we come to this business of ‘infection’ or the transmission of taste. Now, quite plainly this taint cannot be passed on in some unspecified magical fashion; and equally plainly it cannot be physically transmitted, like influenza or syphilis, by means of a germ or virus. What there can be, however, is a form of contagion which is partly moral and partly psychological. Look at it this way. We have seen that a victim is likely to have the masochistic tendencies which his passive role requires of him; and we have remarked, as a matter of medical commonplace, that masochists are often apt to reverse the coin, as it were, and wield the whip themselves. Now, suppose you had someone who had been used by a vampire and subsequently felt the need to express himself sadistically. The chances that his sadism will take a vampiric form are clearly increased a thousandfold by the mere fact that he now knows about vampiric methods. This is a very simple proposition, and applies, mutatis mutandis, to the most elementary forms of sexual behaviour. A small boy at school, for example, feeling without real comprehension the need for sexual relief, will at first resort to some form of masturbation which he has discovered for himself. But once let him be initiated, by a school friend or a girl cousin, into some more elaborate amusement, and henceforth he will scorn self-abuse and seek for a partner with whom to play the new games he has learnt. At first it is a matter of novelty; later it is one of habitual preference and even imperious necessity. It is not so much that a taste has been transmitted as that a technique has been taught ....

Doctors Wear Scarlet (1960) by Simon Raven

https://www.amazon.com/Doctors-Wear-Scarlet-Simon-Raven/dp/1842321803