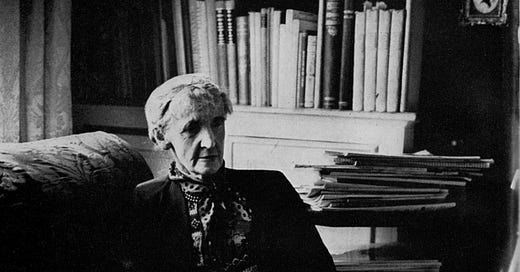

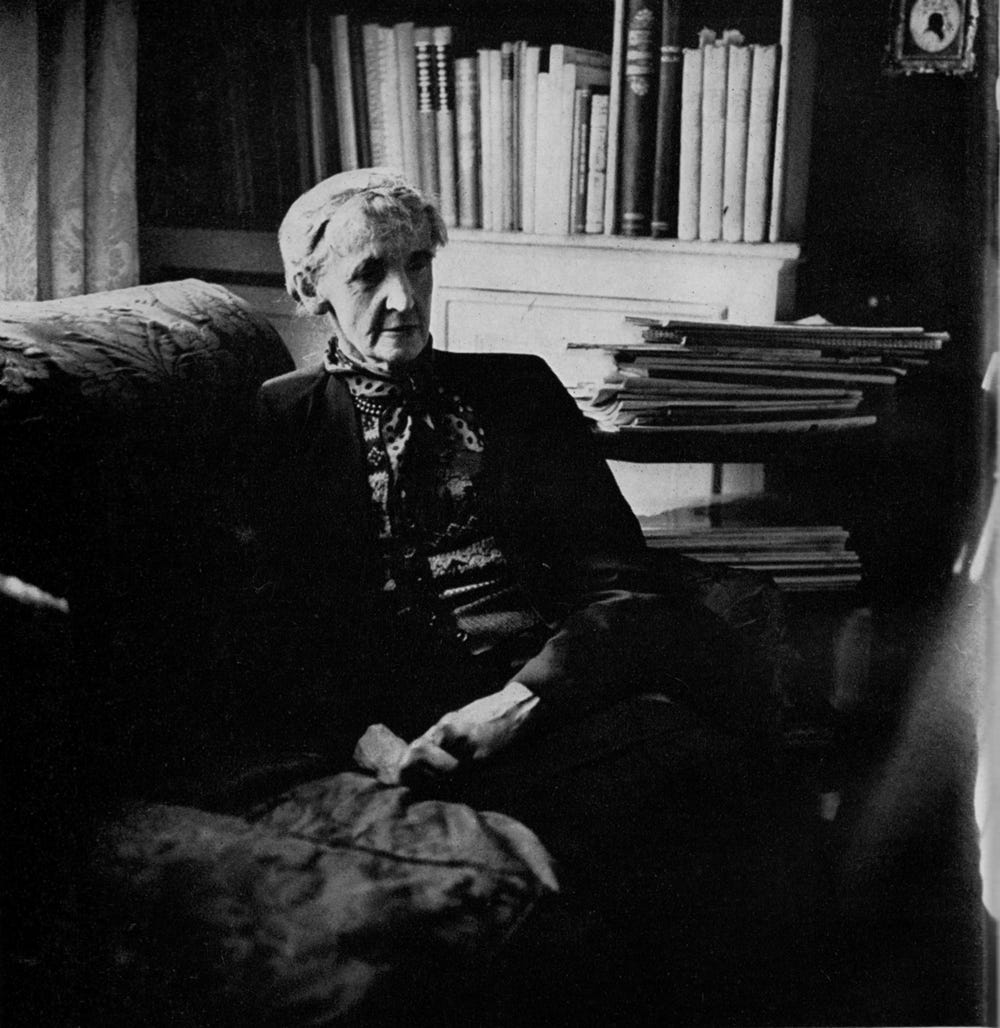

Two stories by Rose Macaulay (1881-1958)

Readers unfamiliar with "The Empty Berth" and "Whitewash" may prefer to read these notes only after reading the stories.

According to the ISFDB, the accomplished novelist and essayist Rose Macaulay (1881-1958) wrote two supernatural stories in her career. Both take place in the Mediterranean. Each follows different British visitors who have contrasting encounters.

Most working writers in what Michael Dirda has called "The great age of storytelling" produced, among a great many types of work, supernatural short stories. Macaulay's are very good, and worth seeking out.

"The Empty Berth" (1913) is a story so effervescent with strange effects and droll humor that it put a spring in my step for the whole day.

The story covers the vacation cruise to Greece of a school teacher, Shipley. He is to share a stateroom with a man named H. Cottar.

….Having for the last two months seen his name, ‘H. Cottar’, coupled with his own (State-room 93) in the printed passenger-lists of the Castle’s April cruise, he had sometimes speculated with a little mild interest on his size, temper, age, and habits. In a cabin six feet square, containing two beds, these things are not unimportant. He hadn’t known anything at all about H. Cottar. He had wondered if he was another schoolmaster, and had rather hoped he was. One gets to feel at home with other schoolmasters, when one has been one for five years or so.

But as Shipley is unpacking, the steward announces:

‘You’ll be alone here, sir. The gentleman, Mr Cottar, that was to have had the top berth, died suddenly three days ago.’

Shipley dines and socializes with his headmaster and family. Macaulay permits herself some M. R. Jamesian jocularity:

He joined Miss Steele, his head’s daughter. She was cheerful, pretty, fair-haired, companionable, pleasant, and neither clever nor stupid; in short, a nice girl. (This has been said above, but there is no more fitting phrase to describe her.) She had her camera, and was taking Marseilles. Shipley got his out, and took Marseilles too. That is the worst of having brought a camera; you must use it. (You may even join the Camera Club.)

But Shipley also learns to appreciate the strengths of the Brown clan, fellow passengers lower in class distinction.

‘The level way to the Arcadian Gate for mother and me,’ said Mr Brown, mopping his forehead. (The Arcadian Gate was where they lunched.) ‘You’d better come along with us, Nance.’

But Nance thought not. ‘Of course Bobby and I are going to the top,’ she said, and started off with vigour. It was a steep and long scramble and a hot noon, and several strong men fainted by the way and lay under trees and had first aid. The Browns did not. They scarcely seemed out of breath. The Steeles got distinctly weary, but conscientiously climbed on. Shipley, too, climbed on, in grim determination. When they got to the top, the Browns ran all the way down at full speed. They were enjoying themselves. Shipley did not see them again till, on the homeward way, he encountered them in a monastery courtyard, drinking tar-flavoured wine and eating Turkish delight and talking to the monks on their fingers. They passed the glass they had half-emptied to Shipley and the Steeles. Miss Steele refused it, in her pleasant, courteous way. Probably she didn’t drink from other people’s glasses. Shipley took it and drank. He gave it back, not emptied, to Miss Brown, who held it out again, as if there had been some one else, at her other side, to take it and drink it too. Then she drew back her hand, recollecting herself, and divided what was left between herself and Bobby. Shipley had an odd feeling of some jolly fellowship that was being sacramented; a fellowship not only of him and the Browns, not chiefly, even . . .

At first Shipley has imaginary conversations with H. Cottar before bed each night. Then the conversations take on a life of their own.

....He meant to ask [Miss Dorothy Steele] to marry him some time; only not early in the cruise, because if she refused him, which he thought she probably would, it would spoil the rest of the time for both of them. He would wait till the homeward voyage.

Lying awake in bed that night, he quite decided this. Two days ago he had meant to ask her before they reached Greece; but after all that would be a silly plan.

‘Oh Lord,’ groaned H. Cottar from the berth above. ‘I suppose either you want the girl or you don’t. And either she wants to have you or she doesn’t. You don’t mean to say you don’t know which, you silly ass? Besides, why should it spoil anything, a plain question and a plain no? You’re both too beastly self-conscious—that’s what’s the matter. Why not ask her now, and then again on the journey back? In fact, every evening after dinner? Nothing like regularity in these things; it breaks down the strongest resolution. But—excuse my asking—what the dickens do you want her for, my dear man?’

‘It’s nothing to do with you,’ said Shipley, stiffly. ‘But I happen to be—to care for her.’

A hilarious chuckle jarred him. ‘But I asked you why? Because she’s pretty? Because she’s polite? Because she always says the thing you expect? Because she’s a Nice Girl? Oh, my dear good chap!’

Shipley, in his imaginary conversations with H. Cottar, always made him out this sort of offensive person. He realised the unfairness of it, and the inevitability. And, with the offensiveness, there was a sort of buoyant vitality, a confident joy and good-fellowship, and somehow an ability that he, trained by his profession in discerning ability, recognised in H. Cottar, which made it impossible to dismiss him as a tiresome bounder.

Not once but many times during the next few days H. Cottar casually and carelessly set him right on some doubtful point of classical or geographical knowledge; and the queer thing was that he always afterwards discovered this information of H. Cottar’s to be correct....

Like Evelyn Waugh, about whom she wrote a superb 1946 monograph, Macaulay is interested in language: it is clearly her delight, and she makes it ours.

["The Empty Berth" is available in The Ash-Tree Press Macabre Volume Two (2000)].

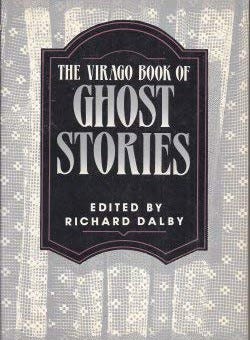

"Whitewash" (1952) can be found in Richard Dalby's essential 1989 anthology The Virago Book of Ghost Stories. I read it here.

In "Whitewash" the young narrator is staying with his or her aunt on the island of Capri. As they swim one afternoon, they discuss the reputation of Capri's most famous former resident, the Roman emperor Tiberius.

The narrator announces current scholarship demonstrates Tiberius was a thoughtful and much-maligned ruler. The aunt doesn't believe a word of it, knowing her Tacitus and Suetonius. She prefers, she says, the Tiberius still feared by the islanders to the Tiberius of the modern "whitewashers."

They part, the aunt to her villa, the narrator to swim around the next point and hunt for a cave. Once inside, he/she is able to climb up on an interior ledge and do some exploring as the day wanes.

Water action begins to sound like voices in extremis; the temperature drops, and a black fin cuts the water just outside the cave's entrance.

"Whitewash" has a relaxed and worldly first-person voice, precise and eloquent in its reticences. The interior cave scene is the strongest depiction of panic terror I have read since L. T. C. Rolts' "The Shouting."

Jay