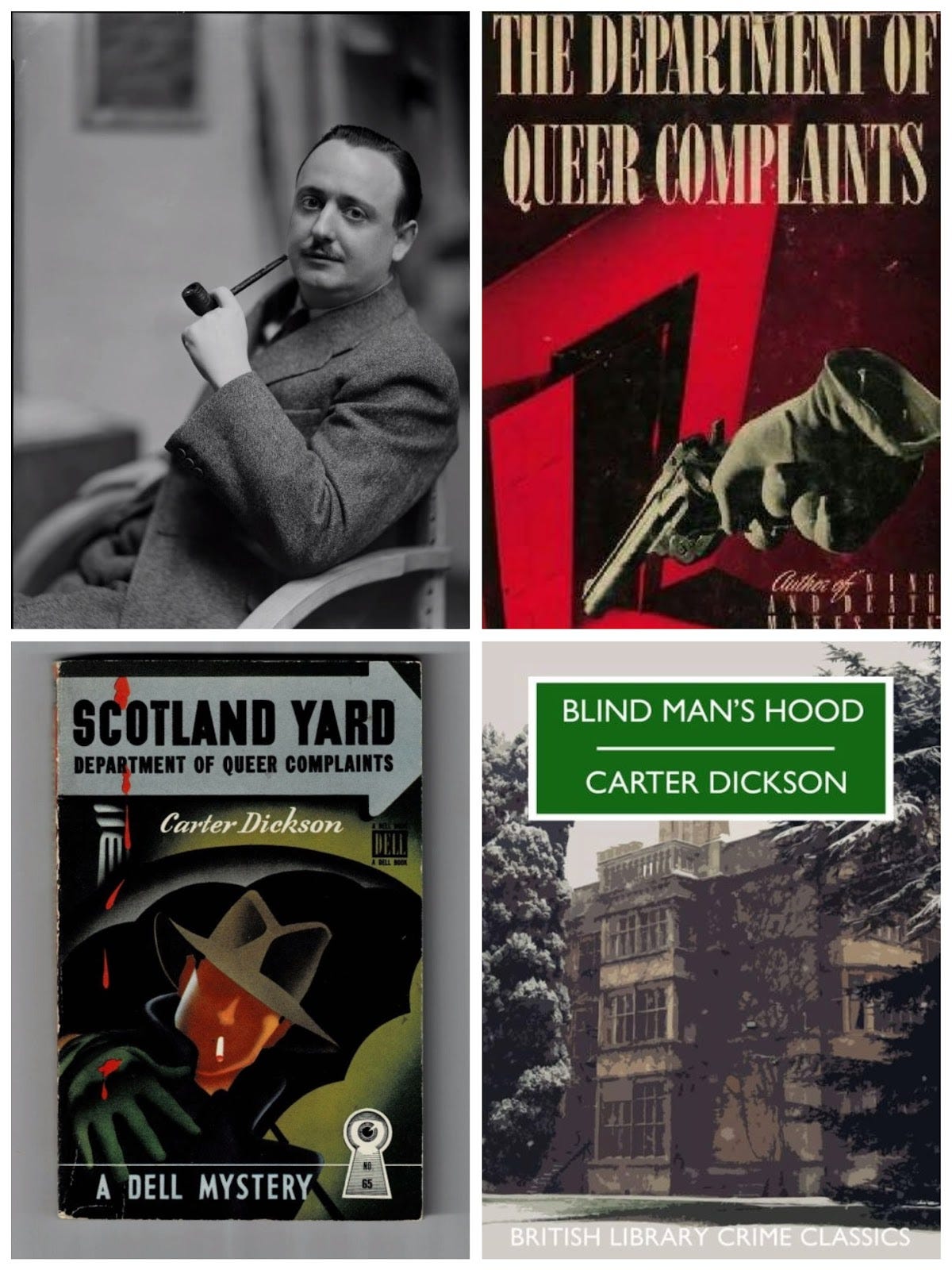

Uncanny John Dickson Carr

Part Two: Strange Tales from The Department of Queer Complaints (1940)

Readers unfamiliar with John Dickson Carr may prefer to read these notes only after reading the stories.

New Murders for Old (1939)

"New Murders for Old" begins it's unsettling run with a twice-told frame: all dialogue, and the apparently omniscient speaker's role is not divulged until the reader has had time to figure it out.

Protagonist Tony Marvell, successful young mogul at Marvel Hotels, has overworked himself to the point of hallucination and blackout. His surgeon brother orders him incommunicado for a round-the-world cruise to recover sanity.

The snowy night Tony returns, he reads this is the newspaper on the train for London:

“‘Mr. Anthony Dean Marvell, of Upper Avenue Road, St. John’s Wood, and owner of Marvell Hotels, Ltd., was found shot dead last night in his bedroom at home. A bullet had penetrated up through the roof of the mouth into the brain, and a small-calibre automatic was in his hand. The body was found by Mrs. Reach, Mr. Marvell’s housekeeper, who....

So much for the rest cure!

Carr presents Tony as akin to a Cornell Woolrich hero: mental illness is foregrounded. Criminality--real or hallucinated–is its symptom. Tony knows no one else has a motive to frame him for his own suicide.

In the train corridor, he notices an old man "wearing a greatcoat with an old-fashioned brown fur collar." His fiancee Judith tells police this was a well known coat worn by Tony's uncle, Old Jim, who started Marvel Hotels and made Tony his heir.

Once he reaches London, Tony realizes he is being followed.

“He knew something was following him before he had taken half a dozen steps. Two hundred yards don’t sound like a great distance. First right, first left, and you're home. But here it seemed to stretch

out interminably, as such things do in dreams. He did not want to leave the

taxi-driver.

The driver thought this was because Tony doubted his honesty about bringing the luggage on when the wheel was repaired. But it was not that.

“For The first part of the way, Tony walked rapidly. The other thing walked at an equal pace behind him. By the light of a street-lamp Tony could see the wet fur collar on the coat, but nothing else.

Afterwards he increased his pace to what was almost a run; and, though no difference could be seen in the gait of what was behind him, it was still there. Unlike you, Tony didn’t wonder whether it might be good or evil. These nice differences don’t occur to you when you’re dealing with something that may be dead.

All he knew was that he mustn’t let it identify itself with him or he was done

for.

“Then it began to gain on him, and he ran.

Tony has a few more encounters, a few more hallucinations, that push him toward the suicide he thinks he has already read about in the newspaper.

"New Murders for Old" is a sidewinder of a story. The solution relies on nothing as pedestrian as the narrator -- or a business or romantic rival -- being the killer. The possibility of a supernatural guardian playing a role is treated with mildest skepticism by Judith and the police.

Blind Man's Hood (1937)

"Blind Man's Hood" is an impressive horror story, carefully prepared and artfully executed. The crime at its center is unspeakable. Aftershocks come with stinger intact, even after sixty years.

The story begins with a trope I have only seen used in one other story: an otherwise placid house that must be abandoned or avoided at a certain hour or day each year. Violators don't survive to bring back reports. At Clearlawns, that hour is 7 pm on Christmas Eve.

Rodney and Muriel Hunter, houseguests, arrive late. Clearlawns is decked for holiday revelry, but empty as the Marie Celeste.

“I say, Rod. Do you think you’d better close it?”’

“Why not?”

“I—I don’t know.”

““The place is getting chilly enough as it is,” he pointed out, unwilling to admit that the same thought had occurred

to him. He closed both doors and shot their bar into place; and, at the same

moment, a girl came out of the door to the library on the right.

She was such a pleasant-faced girl that they both felt a sense of relief. Why she had not answered the knocking had ceased to be a question; she filled a void. She was pretty, not more than twenty-one or two, and had an air of primness which made Rodney Hunter vaguely associate her with a governess or a secretary,

though Jack Bannister had never mentioned any such person. She was plump, but with a curiously narrow waist; and she wore brown. Her brown hair was neatly parted, and her brown eyes— long eyes, which might have given a hint of secrecy or curious smiles if they had not been so placid—looked concerned. In one hand she carried what looked like a small

white bag of linen or cotton. And she spoke with a dignity which did not match her years.

“I am most terribly sorry,” she told them. ‘I thought -I heard someone, but I was so busy that I could not be sure. Will you forgive me?”’

She smiled. Hunter’s private view was that his knocking had been loud enough to wake the dead; but he murmured

conventional things. As though conscious of some faint incongruity about the white bag in her hand, she held it up.

“For Blind Man’s Pluff,” she explained. “They do cheat so, I'm afraid, and not only

the children. If one uses an ordinary handkerchief tied round the eyes, they always manage to get a corner loose.

But if you take this, and you put it fully over a person’s head, and you tie it round the neck”—a sudden gruesome image occurred to Rodney Hunter—““then it works so much better, don’t you think?”’ Her eyes seemed to turn inward, and to grow absent....

To keep Rodney and Muriel in their seats, the young woman tells them two intertwined stories. The first is about the killing of Jane Waycross. She and her husband owned Clearlawns sixty years prior. She died, alone in the house, all doors and windows locked, on a snowy February night. Died horribly.

The second begins:

“But in that case,” insisted Hunter, “who did kill her? And, if there were no footprints and all the doors were locked, how did the murderer come or go? Finally, if all this happened in February, what does it have to do with people being out of the house on Christmas Eve?”

“Ah, that is the real story. That is what I meant to tell you.”

She grew very subdued.

“It must have been very interesting to watch the people alter and grow older, or find queer paths, in the years afterwards. For, of course, nothing did happen as yet. The police presently gave it all up; for decency’s sake it was allowed to rest. There was a new pump built in the market square; and the news of the Prince of Wales’s going to India in ’75 to talk about; and presently a new family came to live at ‘Clearlawns,’ and began to raise their children. The trees and the rains in summer were just the same, you know. It must have been seven or eight years before anything happened, for Jane Waycross was very patient.

“Several of the people had died in the meantime. Mrs Randall had, in a fit of quinsy; and so had Dr Sutton, but that was a great mercy, because he fell by the way when he was going out to perform an amputation with too much of the drink in him. But Mr Pawley had prospered—and, above all, so had Mr Wilkes. He had become an even finer figure of a man, they tell me, as he drew near middle age. When he married he gave up all his loose habits. Yes, he married; it was the Tinsley heiress, Miss Linshaw, whom he had been courting at the time of the murder; and I have heard that poor Jane Waycross, even after she was married to Mr Waycross, used to bite her pillow at night because she was so horribly jealous of Miss Linshaw.

“Mr Wilkes had always been tall, and now he was finely stout. He always wore frock-coats. Though he had lost most of his hair, his beard was full and curly; he had twinkling black eyes, and twinkling ruddy cheeks, and a bluff voice. All the children ran to him. They say he broke as many feminine hearts as before. At any wholesome entertainment he was always the first to lead the cotillion or applaud the fiddler, and I do not know what hostesses would have done without him.

“On Christmas Eve, then—remember, I am not sure of the date—the Fentons gave a Christmas party. The Fentons were the very nice family who had taken this house afterwards, you know. There was to be no dancing, but all the old games. Naturally, Mr Wilkes was the first of all to be invited, and the first to accept; for everything was all smoothed away by time, like the wrinkles in last year’s counterpane; and what’s past is past, or so they say. They had decorated the house with holly and mistletoe, and guests began to arrive as early as two in the afternoon.

“I had all this from Mrs Fenton’s aunt (one of the Warwickshire Abbotts), who was actually staying here at the time. In spite of such a festal season, the preparations had not been going at all well that day, though such preparations usually did. Miss Abbott complained that there was a nasty earthy smell in the house. It was a dark and raw day, and the chimneys did not seem to draw as well as they should. What is more, Mrs Fenton cut her finger when she was carving the cold fowl, because she said one of the children had been hiding behind the window curtains in here, and peeping out at her; she was very angry. But Mr Fenton, who was going about the house in his carpet slippers before the arrival of the guests, called her ‘Mother’ and said that it was Christmas.

“It is certainly true that they forgot all about this when the fun of the games began. Such squealings you never heard!—or so I am told. Foremost of all at Bobbing for Apples or Nuts in May was Mr Jeremy Wilkes. He stood, gravely paternal, in the midst of everything, with his ugly wife beside him, and stroked his beard. He saluted each of the ladies on the cheek under the mistletoe; there was also some scampering to salute him; and, though he did remain for longer than was necessary behind the window curtains with the younger Miss Twigelow, his wife only smiled. There was only one unpleasant incident, soon forgotten. Towards dusk a great gusty wind began to come up, with the chimneys smoking worse than usual. It being nearly dark, Mr Fenton said it was time to fetch in the Snapdragon Bowl, and watch it flame. You know the game? It is a great bowl of lighted spirit, and you must thrust in your hand and pluck out a raisin from the bottom without scorching your fingers. Mr Fenton carried it in on a tray in the half-darkness; it was flickering with that bluish flame you have seen on Christmas puddings. Miss Abbott said that once, in carrying it, he started and turned round. She said that for a second she thought there was a face looking over his shoulder, and it wasn’t a nice face.

“Later in the evening, when the children were sleepy and there was tissue-paper scattered all over the house, the grown-ups began their games in earnest. Someone suggested Blind Man’s Bluff. They were mostly using the hall and this room here, as having more space than the dining-room. Various members of the party were blindfolded with the men’s handkerchiefs; but there was a dreadful amount of cheating. Mr Fenton grew quite annoyed about it, because the ladies almost always caught Mr Wilkes when they could; Mr Wilkes was laughing and perspiring heartily, and his great cravat with the silver pin had almost come loose.

“To make it certain nobody could cheat, Mr Fenton got a little white linen bag—like this one. It was the pillow-cover off the baby’s cot, really; and he said nobody could look through that if it were tied over the head.

“I should explain that they had been having some trouble with the lamp in this room. Mr Fenton said: ‘Confound it, mother, what is wrong with that lamp? Turn up the wick, will you?’ It was really quite a good lamp from Spence and Minstead’s, and should not have burned so dull as it did. In the confusion, while Mrs Fenton was trying to make the light better, and he was looking over his shoulder at her, Mr Fenton had been rather absently fastening the bag on the head of the last person caught. He has said since that he did not notice who it was. No one else noticed, either, the light being so dim and there being such a large number of people. It seemed to be a girl in a broad bluish kind of dress, standing over near the door.

“Perhaps you know how people act when they have just been blindfolded in this game. First they usually stand very still, as though they were smelling or sensing in which direction to go. Sometimes they make a sudden jump, or sometimes they begin to shuffle gently forward. Everyone noticed what an air of purpose there seemed to be about this person whose face was covered; she went forward very slowly, and seemed to crouch down a bit.

“It began to move towards Mr Wilkes in very short but quick little jerks, the white bag bobbing on its face. At this time Mr Wilkes was sitting at the end of the table, laughing, with his face pink above the beard, and a glass of our Kentish cider in his hand. I want you to imagine this room as being very dim, and much more cluttered, what with all the tassels they had on the furniture then; and the high-piled hair of the ladies, too. The hooded person got to the edge of the table. It began to edge along towards Mr Wilkes’s chair; and then it jumped.

“Mr Wilkes got up and skipped (yes, skipped) out of its way, laughing. It waited quietly, after which it went, in the same slow way, towards him again. It nearly got him again, by the edge of the potted plant. All this time it did not say anything, you understand, although everyone was applauding it and crying encouraging advice. It kept its head down. Miss Abbott says she began to notice an unpleasant faint smell of burnt cloth or something worse, which turned her half ill. By the time the hooded person came stooping clear across the room, as certainly as though it could see him, Mr Wilkes was not laughing any longer.

“In the corner by one bookcase, he said out loud: ‘I’m tired of this silly, rotten game; go away, do you hear?’ Nobody there had ever heard him speak like that, in such a loud, wild way, but they laughed and thought it must be the Kentish cider. ‘Go away!’ cried Mr Wilkes again, and began to strike at it with his fist. All this time, Miss Abbott says, she had observed his face gradually changing. He dodged again, very pleasant and nimble for such a big man, but with the perspiration running down his face. Back across the room he went again, with it following him; and he cried out something that most naturally shocked them all inexpressibly.

“He screamed out: ‘For God’s sake, Fenton, take it off me!’

I give this extended quotation from the spectacular last half of "Blind Man's Hood" so that the reader can see the scope of Carr's horror achievement. Every element, every turn, has been prepared and is executed flawlessly. This denouement illustrates Ramsey Campbell's point that in Carr's fiction "sometimes the cosiness grows chill, the setting slips to let something out of M. R. James peer through."

While peering, or guarding, may describe the revenant in "New Murders For Old," there is precious little peering in "Blind Man's Hood." The charred remainder of Jane Waycross gets on just fine with the bag securely over her head.

Jay

5 July 2023