"What?" And "How?" In E. A. Poe

How to Read Texts: A Student Guide to Critical Approaches and Skills (Bloomsbury, 2nd Edition 2013) by Neil McCaw

How to Read Texts: A Student Guide to

Critical Approaches and Skills by Neil McCaw is well worth the amateur/non-student reader's time. I have been inhabiting it for about two weeks. It is rewarding and provocative in the same way as the superb Bennett and Royle books.

McCaw begins with an overview of reading skills as we develop them in primary and secondary school. He spends the remaining chapters exploring shifts and changes college-level reading and writing will demand of young scholars.

McCaw is never dogmatic:

If you feel insecure about your reading then you need to understand that if people (even teachers/tutors) suggest that you read certain texts instead of others there is nothing to say that what they have suggested is any ‘better’ than the alternatives; or that any gaps in your textual knowledge are to be fretted about. There are always texts that even the most apparently educated person won’t know – no-one has the time to read/watch/examine everything. So relax in your ignorance, we are all ignorant in one way or another. You should also try to avoid feeling that the texts you do read are not suitable, appropriate, significant, or serious enough (unless, of course, you aren’t reading anything at all, which would be a shame). An interested (and hopefully interesting) academic reader/interpreter finds value in working with a wide range of texts, even those which might be regarded by some as not worthy of serious consideration....

[….] the idea that there is a single, objective (‘true’) meaning of a text is closer to myth than it is to truth. So stop worrying about it. And second, take confidence from the fact that everyone doubts themselves in this way at one point or another; but as long as you pay close attention to each text, and can support your interpretations with evidence, you won’t go too far wrong.

McCaw's book aims at training readers in fruitful ways to "pay close attention to each text" and marshal evidence for an essay. These procedures are practical and are offered with myriad examples from texts with which students may already be familiar.

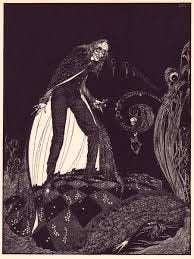

His discussion of Edgar A. Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart" is vivid and instructive. McCaw uses it as a lab experiment in how to employ "what?" and "how?" questions.

Reading creatively in practice: Edgar Allan Poe, ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’26

Starting with the ‘what?’ and ‘how?’ questions

A close reading of the ‘what?’ of Poe’s story soon blurs with the question of ‘how?’ it is told, for it is through its point-of-view that Poe achieves what might be called the psychotic immediacy of the story, with the reader drawn in to the frenzied ramblings of the murderer, invited into a world of truths and half-truths, claims and inconsistencies: ‘TRUE! – nervous – very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad?’ (p. 277). The effect of this direct (second person) address is disconcerting and destabilizing. It challenges the reader and identifies them with a wider world in conflict with the paranoid narrator: ‘How, then, am I mad?’ (p. 277) Throughout the story Poe skilfully utilizes this manic narrative point-of-view to capture the sense of confusion; it is a metaphor for the belligerent and bewildered mind of a murderer: ‘I was never kinder to the old man than during the whole week before I killed him’ (p. 277). As the plot unfolds this mania grows: ‘I knew it was the groan of mortal terror. It was not a groan of pain or of grief – oh, no! it was the low stifled sound that arises from the bottom of the soul when overcharged with awe. I knew the sound well’ (p. 278). The narrative voice encapsulates a troubled life and diseased psychology: ‘I knew what the old man felt, and pitied him, although I chuckled at heart.’ (p. 279) This is made more effective through a repeated switching between direct second-person address to the reader (‘you cannot imagine’ (p. 279)), more orthodox first-person narration (‘when I had waited a long time’ (p. 279)), and non-specific, non-directed address and exclamation (‘Almighty God! – no, no!’ (p. 281)). The reader is witness to multiple voices and multiple personalities.

The ‘why?’ questions

The nature of this narrative voice is a part answer to the question as to ‘why?’ the story is presented in its particular form; it is trying to conjure up specific emotional responses in the reader. But the question as to ‘why?’ Poe’s tale is significant is more complex than this. And central to understanding this complexity is the depiction of the heart as the cornerstone of the narrative. For this functions as an important symbol destabilizing the murderer mentally and precipitates his final-act confession of guilt, embodying all that he is afraid of in the world, residing (literally) beneath the surface (under the floorboards). It has a key connection to the narrator’s murder of the old man: ‘his eye…he had the eye of a vulture – a pale blue eye, with a film over it’.27 All of which represents an underlying repression within the story which manifests in fear, anxiety and overwhelming mental fragility. Right at the beginning the narrator confesses that: ‘I loved the old man’ (p. 277), indicating that the overarching air of repression has sexual dimensions. Neurosis about the all-seeing eye of the old man could indeed be rooted in intimate knowledge of the nature of the narrator’s desire, with the nagging beat of the disembodied heart a symbol of a secret life that lives on, demanding to be revealed. The final paragraph, in which the narrator confesses all to the awaiting policemen, his figurative ‘coming out’, becomes crucial in this context.

Moving through the ‘what?’/‘how?’/‘why?’ stages of reading quickly establishes the outline of a layered interpretation of Poe’s story. An initial examination of how the tale functions leads into a consideration of ‘why?’ it is configured in such a fashion. But the creative-critical interpretative process cannot stop there. Creativity in reading need not be just a matter of trying to find new things to say but can also be about engaging creatively with texts in a more practical sense. One way of doing this is through the form of creative reading/re-reading known as textual intervention.28 Textual intervention is where a reader enhances their reading of a text through altering or extending it, a rewriting exercise in which one or more of the key features of the original are changed, such as the historical period, the genre, the nature of key characters, or the tone or style. Readers produce a piece of creative writing which grows out of the original text and when the two are read alongside each other the features of the originating text are highlighted: ‘the best way to understand how a text works … is to change it: to play around with it, to intervene in it in some way (large or small), and then to try to account for the exact effect of what you have done’ (p. 1). Such a creative and critical exploration can then play a key role in a multi-layered creative reading process:

you will constantly and with every tool at your disposal – critical, analytical, theoretical and historical – be forced back into it [the original text]. Every turning you take, every choice and combination you make will be gauged against one already taken and made in your base text (p. 2).

This process of intervention is effectively one of adaptation, wherein the reader/writer produces a ‘version, variation, interpretation, continuation, transformation, imitation, pastiche, parody, forgery, travesty, transposition, revaluation, revision, rewriting, [or] echo’29 of the first work. In the case of the Poe story, for instance, a potential ‘intervention’/‘adaptation’ would be to re-imagine and rewrite the story as if the narrator (whose role we have already judged to be crucial) is female. In that context, we might consider how the language takes on different significances: ‘I was never kinder to the old man than during the whole week before I killed him’ (p. 277). Does the emphasis and impact alter in the rewriting of the text, and is the disturbed mental state of the narrator amplified or qualified by the change of gender?: ‘I knew what the old man felt, and pitied him, although I chuckled at heart’ (p. 279).

The gendering of the narrator also potentially alters the symbolic significance of the hidden heart in relation to the issue of illicit sexual desire. The connotations of ‘I loved the old man’ (p. 277) change with a female protagonist, altering the dynamics of any supposed wish to hide illicit sexual desire. The result of the creative intervention is thus that we increasingly notice, when reading from the intervention back to Poe’s own story, quite how heavily gendered the narrative voice is in the originating tale. Our attention is drawn to how gender is part of our interpretation and understanding of the manic language and hidden sexual meanings we initially judged as implicit in the story. The result of all this, hopefully, is that our reading of the primary text becomes more subtle and insightful through the multi-faceted linking of our creative and critical skills.

Checkpoint 2

To test your understanding of the ideas discussed in this chapter consider the following:

●What do you understand by the term ‘creative reading’?

●What do you think is/should be the relationship between your critical capabilities and your creative skills?

●Create your own ‘intervention’ into ‘The Tell-Tale Heart,’ imagining the story with ONE key change made to the original.

●Contrast your version of the story with the original and think about what elements your ‘intervention’ sheds new light on.

Notes

26This story is available online in a number of places, including The Online Literature Library; see http://www.literature.org/authors/poe-edgar-allan/tell-tale-heart.html

27Edgar Allan Poe, ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ in The Fall of the House of Usher and Other Writings, edited with an introduction by David Galloway (London: Penguin, 1986), p. 277. Subsequent references to this story in parentheses within the main body of the text.

28See Rob Pope, Textual Intervention: Critical and Creative Strategies for Literary Studies (London: Routledge, 1995). Subsequent references to this publication in parentheses within the main body of the text.

29Julie Sanders, Adaptation and Appropriation (Oxford: Routledge, 2006), p. 18.

Jay

A recent audio version of "The Tell-Tale Heart" is available here:

Animated 1954 version: