"Have you ever heard of a book, an extremely special book, that is not…yes, that is not about something, but actually is that something?”

"Vastarien" (1987) by Thomas Ligotti

Readers unfamiliar with Ghostwritten may prefer to read these notes only after reading the collection.

"The Skin of Her Teeth"

(madness by osmosis)

Imagine a story living cozily in the mollusc shell of its physical book. She came into being through the complex emotional and artistic dialectic of time and place of composition. She is loving, generous, and gives of herself to anyone in need. She is the Pollyanna of stories.

"The Skin of Her Teeth" is not about that kind of story. "The Skin of Her Teeth" is about the evil twin of the loving story described above. The story in "The Skin of Her Teeth" tolerates no division, correction, tampering, or touching that risks alteration. If she senses danger, she hides just like a lost sock. If she's restricted, she breaks loose, chewing through boxes, purses, and crates. Persistent human threats are thwarted, then eliminated, by a combination of physical and mental assault.

She and her kind have few recognized experts; as yet there is no zoology of predatory stories.

A layman named Ross Finter, who owns a bookstore on Worth Street in Manhattan, knows this type of animal. In fact, he runs a kind of shelter for them, keeping them away from their natural enemies: playwrights and screenwriters who want to tear them apart and reassemble them following dramaturgical logic. Which is no way to treat a lady.

“What do you mean it’s not actually a book?”

“Well, you see,” Finter said, wrinkling up his face as he studied the Fish novel on his desk; he kept poking it with the ruler. “It’s a container of sorts. A totem that only looks like a book. But in actuality, that is just the form it takes in our world....”

“Listen here,” he said. “This book—you must think of it like the shell of a mollusk. A thing lives inside it.”

“A female thing,” Gloria said.

Ross Finter gave her a shark’s smile.

“Whatever lives inside this book,” Finter said, “it wants to remain. That is its sole purpose, do you hear? To remain. She doesn’t want to leave, and she certainly does not want to be altered. She does not want change. This…this product here,” he said, tapping the screenplay with the ruler. “This base thing threatens her. It attempts to change her, to alter her. To do away with her. She won’t have it.”

“You mean because the story has to be changed to work for a film—”

“The story does not want to be changed,” Finter said. “The entity that resides inside the story does not want it changed. You cannot alter the story.”

“What are you telling me? That this book is possessed?”

“It’s not the book, madam, but the story. Aren’t you listening? There is nothing special about this particular book—its paper and cardboard and glue and ink. It’s the story that doesn’t want to be changed. It’s really that simple.”

“So what the hell happened to the screenplay?” Gloria asked him. “Where’d the pages go?”

“Quite simple,” Finter said. “The book ate them.”

Gloria sucked on her lower lip and stared at the little man.

“It does not want this version to exist,” Finter went on. “It wants to remain as it has always been, and does not want to change. My suggestion to you, madam, is to let it be.”

He turned and waddled down the length of the shop, one index finger extended like a divining rod. Gloria noticed that he was not looking at books on the shelf, but at a series of metal safes stowed back there on the shelves. A whole collection of them.

Finter selected one, held it up to one ear, shook it.

“Empty,” he determined, and carried the safe over to his desk. He set it down, fished a ball of keys from a retractable wire attached to his belt, and unlocked the safe. It was empty. Before doing anything, he looked back up at Gloria and said, “May I?”

“Go for it,” she said.

He placed the paperback novel inside, then tucked McElroy’s screenplay in after it. He locked the safe, let the keys retract, then placed the safe back on the shelf, among the others.

“I can’t wrap my head around any of this,” Gloria said. “This is a bad dream, right?”

“Whatever gets you through the night, madam,” said Finter.

“That book,” she said, and then said nothing.

“Yes?” said Finter, climbing back onto his stool.

“I think it ate my cat.”

Ross Finter nodded, rubbing his chin. “Quite possible,” he said. “Quite possible, indeed.” (Malfi, Ghostwritten 59-61)

* * *

Malfi narrates "The Skin of Her Teeth" beginning near the end of the story's wanderings and killings. His protagonist investigates, filling in the background. Absurd and comical moments are handled deadpan, as are accounts of the shocking ends of various playwrights and scriptwriters.

Characterization is deft and economical. Readers who enjoyed Nathan Ballingrud's Jack Oleander stories will find moves and tones to appreciate here.

Cat lovers? Not so much.

"The Dark Brothers’ Last Ride"

(“precious cargo”)

Choptank collects books. In a liminal desert hinterland called The Mesa, he uses the books to correct effects of other books that have had a malignant effect on our reality.

When Choptank has a book delivered to him, driving directions are ritualistic and eccentric to say the least. When the curious or stubborn deviate, an imbrication of worlds begins; empty desert towns appear, their carry-outs filled with unusual brand names. Unusual unless you come from a place where Budscheisse (“whatever the hell that was”) beer is popular.

From the human world, Choptank – also known as The Cleaner – purchases a book. It is more living plant than prosaic work of bound cardboard, glue, and paper. The seller goes by the name of Finter. The Ukrainian middleman on the US West Coast arranges delivery to Choptank.

“To begin with, the briefcase is locked and cannot be opened. Only the client and Choptank have keys to open it. That is how I received it from the client, and that is how you will deliver it to Choptank. I am aware that you operate with utmost professionalism, Danny, but I was asked to make this part very clear. The briefcase is to remain locked and the item is not to be removed from it under any circumstances.”

“Understood,” Danny said.

“I was also instructed to tell you that the item inside the briefcase is particularly delicate. Under no conditions are you to touch it.” Rudenko’s gaze shifted over to Tommy. “Neither of you.”

Tommy scratched at the beard stubble along his neck. He said, “If it’s in a locked briefcase that we can’t open, how’re we gonna touch—”

“Understood,” Danny repeated, cutting his brother off.

Rudenko’s jungle-cat gaze hung on Tommy for a beat longer than Danny was comfortable with. “As I’ve mentioned,” Rudenko continued, his eyes ticking back over to Danny, “I’ve been provided a map for your use. The route our client has requested you take has been outlined for you. No doubt you’ve already done the math in your head, Danny, on the timeline to get from here to the Arkansas border—”

“Should be about a twelve-hour drive, depending on conditions. Tonight’s Thursday, so if this Choptank guy is meeting us at noon on Saturday, that leaves us plenty of time.”

“Under normal circumstances, you’d be correct. You will find, however, that my client’s specified route of travel is rather…circuitous. There cannot be any deviations; it must be that route exactly. You’ll need to leave this evening if you’re to make it on time.”

This evening? That made no sense to Danny, but he just nodded his head.

“Lastly, if anyone approaches you and asks about the book—to see it, to hold it, anything at all—your instructions are to ignore them. That was the word the client himself used—ignore. In most cases, he said that should work. He added, however, that if any of these individuals persist and make it difficult for you to complete your assignment—if they cause you any additional aggravation or trouble, in other words—the client has suggested it be best to use any force necessary to avoid complications or further dealings with these people.”

Danny shook his head. “I don’t understand. Who would we run into?”

“I do not know.”

“Does anyone even know we’re in possession of this thing? Other than this guy Choptank and this anonymous client?”

“Not to my knowledge,” Rudenko said. “I am merely passing along the instructions as I have received them. My advice is that we operate to the letter and ask no questions.”

“All right,” Danny said.

(Malfi, Ghostwritten 93) [Emphasis in original].

* * *

“The worlds are dangerous places,” Choptank said

"The Dark Brothers’ Last Ride" is a sharp-cut crime tale: Jim Thompson's bloody Gnostic crossroads cannot be far.

On the next road over, perhaps, Warren Oates is still trying to deliver the head of Alfredo Garcia.

"The Dark Brothers’ Last Ride" is not a coming-of-age story, though the reader is able eventually to review all the coming-of-age horror anyone could stomach. It's not pretty, but it rings solemnly true and real. The US southwest is carefully evoked: all-night diners and dead-eyed waitresses, and black goats with wings as glimpsed from two-lane blacktop.

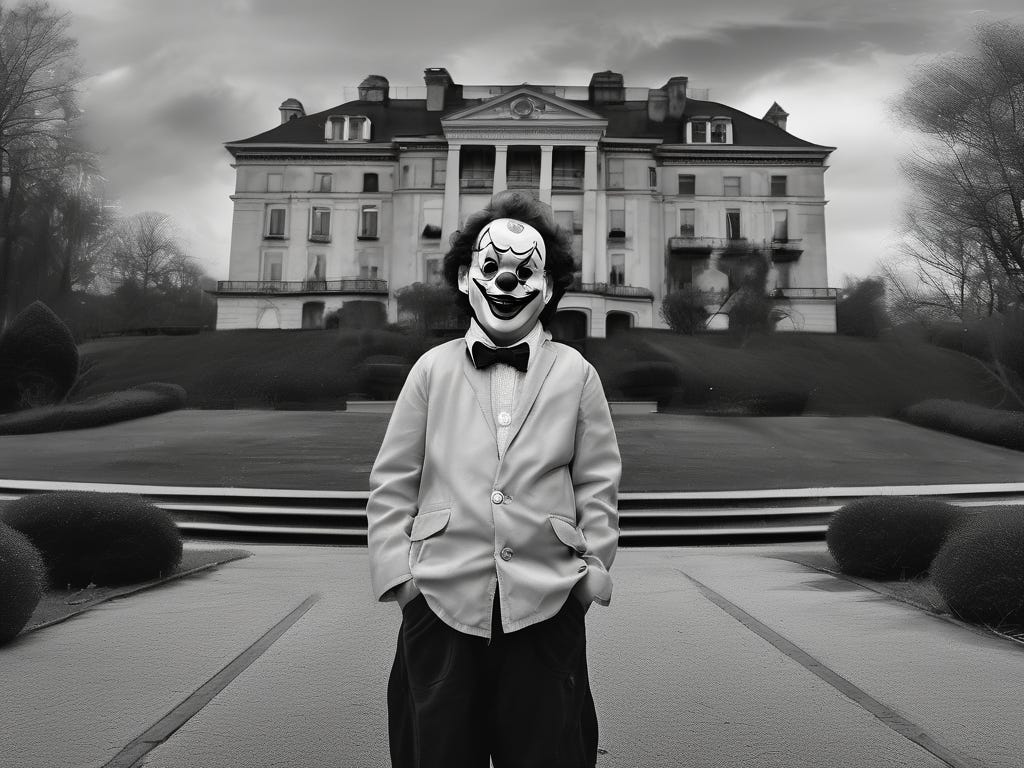

"This Book Belongs to Olo"

(The brain-shout)

"This Book Belongs to Olo" is the third story in Ghostwritten. Living up to the collection's title, it is the most inward-turning and uncanny work we have thus far encountered.

It reminded me of the observation: "A plot unfolds to articulate desire." (Fry 205)

"This Book Belongs to Olo" has the least articulate protagonist we have encountered thus far in Ghostwritten. Olo is ten, perpetually wearing a clown mask he slides up or down over his face depending on mood and circumstance. As though cops, adults, and kids (from the local playground) might otherwise have trouble shunning him.

For these onlookers-victims, Olo is a spectacular oddball: the home-schooled friendless loner who grows more insidious each day.

Not that his mother, famous mystery novelist Maribel Sinclair, and stepfather Roger Smalls display as normal.

“Why didn’t you mention your birthday was this Saturday?”

“Birthday?” Roger said. He was blinking and screwing his head around like an owl. His big, confused eyes settled on his stepson. “Is it really? This Saturday?”

Olo resisted the urge to tug the mask back down over his face. Instead, he grasped his glass and took a few thirsty gulps of his chocolate milk.

“Your mother’s right, sucker punch. You should have said something to remind us. You know how your mother and I get when we’re knee-deep in our writing.”

“Well, now I just feel awful,” Maribel said. “Did you want to come with me to New York, darling? Celebrate in the city?”

“No, thank you.”

“Are you sure? You could have a grand time, walking around and taking in the sights while I’m at the expo.”

“We can just celebrate my birthday when you get back,” Olo suggested. “This way Roger can attend his publishing event and you can go to the expo and there won’t be any conflicts.”

Roger slapped his hands together, loud as a pistol shot. “Stellar! The boy’s a goddamn genius, as we know! And of course this means we’ll have to go doubly big when your mother returns. I’m talking balloons, presents, a dinosaur cake or whatever your little heart desires, Olo. The whole nine yards. And you can invite whomever you’d like. We’ll throw a wild bash right here at the house, just like the old days.”

The wild bash that had been thrown for Olo’s birthday last year had involved Roger in a pointy hat drunkenly singing “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” out on the patio while Mr. Cooper, their former groundskeeper, led Olo in circles on the back of a rented pony. Ms. Betty had dressed one of the outdoor picnic tables in all of Olo’s favorite foods, while Olo’s mother had smoked cigarettes and argued on her cell phone from beneath the shade of a large oak. After the pony rides and the presents, they had all watched Olo devour an entire carton of chocolate fudge ice cream capped in a summit of whipped cream and rainbow sprinkles.

“You mean it?” Olo said. “I can invite anyone I want?”

“Well,” Maribel said, resting one cold hand atop Olo’s. Her palm was ice. “I think your family is all the friendship you need for the time being. Not to mention the characters in your books, of course—Robinson Crusoe, Henry Fleming, Humbert Humbert…”

Roger made a sour face. “He’s read Lolita?”

“The point is,” said Maribel, “we don’t need another incident like that time I mistakenly sent you to public school.”

“That was a long time ago,” said Olo. “I was only six.”

“Nonetheless, it’s still left a bad taste.” She tilted her head back slightly, as if tempting him to continue his argument. “You’re sure you don’t mind both of us being out of the house for your birthday, dear?”

“I don’t mind,” he said, reaching again for his chocolate milk.

“Then it’s settled,” Roger said, his loud voice echoing throughout the room. “Crisis averted.”

“I’ll make a note and have a cake delivered,” Maribel said, typing into her phone. “I assume chocolate will suffice?”

“Double chocolate,” Olo said.

“Now the boy’s thinking,” Roger said, grinning. There was a comet’s tail of soy sauce on the front of his oxford shirt. “Goddamn it, why shouldn’t there be double chocolate?. (Malfi 208)

* * *

Olo has passed the "little Hans" stage of childhood desire. He has perfected, or been perfected by, a homemade pop-up book that doubles as a collection jar. It's not a killing jar, but those captured might as well be dead.

Behind him, in the dark, it sounded like the doors were rearranging themselves.

Olo's friend-collecting, mind-bending, reality-warping book can be read as a powerful metaphor for horror's handling of coming-of-age wrongness. Olo has come to the end of what would normally be the elementary school stage, and is proceeding into pubescence, beginning to toy with plot materials of the Family Romance. His interactions with Maribel have been displaced, and he has "disappeared" his young tutor, Iris, a mother stand-in who was on the verge of quitting in order to marry and move to California.1

"This Book Belongs to Olo" is Realist in treatment of family predicaments. But the handling of uncanny and fantasticated material raises stakes for readers to intimidating heights.2 Malfi’s treatment of unsettling temporalities Olo controls by some unknowable and unnameable witchcraft is immaculately distanced and cool. This fine-grained and audacious art defies assumptions of today's mainstream commercial horror business and its shoppers.

"The Story"

(a less identifiable pungent funk)

Podcast performers (I almost wrote "journalists") unveiling mysteries and solving crimes: this pitch begs the question – could they ever solve a mystery, or must they only forever retail the Sherlock skills of professional sleuths: the cops?3

A podcaster drawn back to old dramas (personal and professional) as he works to solve the apparent suicide of a former lover sounds like an overinflated thriller novel recipe: probably unreadable and irredeemably high-concept and bound for Max streaming. Journalists cracking cases and saving the world used to be cliché bestseller plots in the wake of Pentagon Papers and Watergate. Woodward and Bernstein wrote All the President's Men as a third person thriller with all the trappings of the "nonfiction novel," entirely devoted to depicting themselves as the intrepid heroes. Unless I missed its appearance already, we cannot be far from the crusading podcaster thriller.

* * *

“You’re not hearing me, man.” He actually pounds the table with a fist. A few heads swivel in our direction. “It’s not just a book. It’s something more. It burrows in your brain. It feeds you things and you find yourself trying to digest it all. Next thing you know, you can’t tell what’s real and what’s part of the Story.”

“The Story” is a mystery story that, before we or the narrator are ready, will swallow its own tale–and blip out of sight–like an ouroboros.

In it, podcaster and journalist Grady Russo fights to understand the suicide of former lover/employer Taryn Donaldson. When they initially met:

We slept together that night. She was one of those girls you knew you could sleep with right away. Not because she was easy, but because she wanted to sleep with you just as much as you wanted to sleep with her, and she made no attempt to hide it. We went back to my apartment, and she was this wily, pale, frizzy-haired thing in flaking black nail polish. When we were done, she dressed, pressed the tip of her nose to mine, and said, “Don’t fall in love.” Then she fled.

At the end of “The Story,” we and perhaps the dying (or not dying) Grady realize “Don’t fall in love” might have been Taryn’s warning to herself, not to a new lover.

Unending ambiguity flavors the world of weird topic podcasts. Taryn and Grady’s podcast, The Spectral, is no exception. It attracts a listener who wants Taryn to track down a dark web app story that might warp waking life, or warp its awake consumers until their choices and perceptions are indistinguishable from sublime hysteria.

“The Word” is Malfi daring, working to thwart the everydayness of fictional operations. At the same time, Malfi struggles to make-new trite, clichéd tropes. Malfi’s skill is in misdirecting both his readers and protagonists, even though in the end the pull of solipsism’s mind-screw is too enticing to escape.

* * *

Ghostwritten features no ghosts. Its few specters can be explained to the reader's satisfaction as hallucinations. Likewise, Ghostwritten features no ghost writers. There are a few writers, and people who proclaim themselves writers, but no Kubrickian Jack Torrance qwerty goblins shackled to remorseless platens.4

Writing horror/spectral stories is an exercise in erasing and over-writing: each author contributing their mite on what they assume is a perfectly cleaned page; only when they finish “their” story does the living writer realize how much of the old still remained before they began: “their” page was a place where words of predecessors – uncannily – persisted.

Malfi’s moves in Ghostwritten are time-honored to horror readers. This familiarity is not the product of plagiarism or conscious authorial borrowing. It comes instead from skill in deploying horror's repertoire of unsettling subversions, and the writer's confidence in each horror reader's responsiveness to them.

Jay

20 January 2024

Sources

Fry, Paul H. Theory of Literature. Yale UP, 2012.

Malfi, Ronald. Ghostwritten. Titan Books, 2022.

Notes

N.B. Olo's goals as a ten year old kidnapper are humble and poignant: to have friends. But only under his own terms: playing only the games he enjoys, sharing only the snacks and drinks he enjoys. Malfi mentions no sexual curiosity on Olo's part toward his captives, which seems unusual considering he has already read Lolita

N.B. "Olo" is a piece of fiction steeped in an atmosphere of unease and wrongness. It gracefully accomplishes this law of horror fiction:

Inconceivable events and conditions form a class apart from all other story elements, and cannot be made convincing by any mere process of casual narration. They have the handicap of incredibility to overcome; and this can be accomplished only through a careful realism in every other phase of the story, plus a gradual atmospheric or emotional building-up of the utmost subtlety. The emphasis, too, must be kept right—hovering always over the wonder of the central abnormality itself. It must be remembered that any violation of what we know as natural law is in itself a far more tremendous thing than any other event or feeling which could possibly affect a human being. Therefore in a story dealing with such a thing we cannot expect to create any sense of life or illusion of reality if we treat the wonder casually and have the characters moving about under ordinary motivations.....

In his 2009 novel Creatures of the Pool (reviewed here) Ramsey Campbell has as protagonist a Liverpool walking-tour guide unraveling mysteries that snag his own life. Many of Campbell's amateur finders-out crack hallucinatory mysteries about films (Ancient Images, The Grin of the Dark). The Doll Who Ate His Mother features a journalist as part of a duo investigating a strange something that Campbell will pick up time and again in his sixty years as a fiction writer.

Grady Russo is a name that risks a knowing smirk from horror readers. John Russo and the Russo brothers have, separately, made their contributions to horror and thriller genres. “Captain America: Winter Soldier,” directed by the Russo Brothers, is filled with nods to 1970s political thriller films. (Not for nothing does it feature Robert Redford subverting his All the President's Men performance).

And the name Grady will be familiar to readers of Stephen King and viewers of Stanley Kubrick.